Meetings: Career Advice from Nobel Laureates

Many young physicists dream of one day getting the call from Stockholm announcing their Nobel Prize. But how does one attain such heights of success? Are certain fields or career paths better than others? Well, who better to ask than a room full of scientists who have fulfilled this dream? This past June at the Lindau Meeting, 29 Nobel Laureates mingled with 400 young researchers from around the world for a week of science talks and socializing. Occasionally, the discussions touched on career choices, and a common theme was follow your curiosity—even if it leads you down a road less traveled.

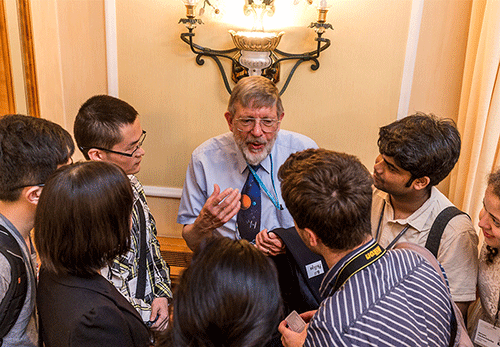

The Lindau Meeting is held annually on the postcard-perfect shores of Lake Constance in Germany. For one week each summer, the charming Bavarian town of Lindau becomes a brain funnel, concentrating several dozen Nobel winners together for lectures, panel discussions, and seminars. In attendance are several hundred graduate students and postdoctoral researchers, who are selected by various institutions in their home countries. The organizers make time in the program for the Laureates to meet these young researchers at breakfast get-togethers, barbecues, and boat rides. “It is a very unique meeting, where one can connect with selected young people from many different countries who are eager to discuss all kinds of questions,” said Theodor Hänsch (2005 Nobel Prize; frequency comb), a veteran participant who has attended eight Lindau meetings over the years.

The theme of this year’s meeting was physics, so attendees were treated to talks on neutrino oscillations, Higgs bosons, gravitational waves, and even soap bubbles. The discussions were intensified with a who’s who list of science pioneers. Highlighting the “star studded” nature of the event, Bill Phillips (1997; laser cooling and trapping) stopped in the middle of an explanation of Josephson junctions to walk across the stage and point out Brian Josephson (1973; tunneling effects) in the audience. “Isn’t this fantastic?” Phillips remarked. He asked Josephson how old he was when he came up with his now-famous junction. The answer, 22, prompted Phillips to playfully chide his audience: “How’s that for a challenge for you young people?”

Some of the Laureates offered advice and encouragement on dealing with the challenges of a scientific career. In his talk, Hiroshi Amano (2014; blue LEDs) described the main choice he faced as a young scientist: whether to follow the majority and choose a “hot topic” that gave high odds for journal papers and faculty positions, or take on a lower-profile pursuit that others had abandoned or neglected. He chose the minority path—with an obvious payoff. Should other young scientists do the same and go it alone? “If they can be confident with their research, then they should continue,” Amano said.

Hänsch had a similar message for scientists choosing a career. “My personal inclination is to work on small-scale experiments that I can do myself,” he said. In a small group, Hänsch said, you can learn from your mistakes faster. His own mentor, Arthur Schawlow (1980; laser spectroscopy), gave him some important advice when he was just starting out: if you want to discover something new, “try to look where no one has looked before.” And for those hoping to get a Nobel Prize, Klaus von Klitzing (1985; quantum Hall effect) had this prescription: cross Lake Constance to Switzerland and eat lots of chocolate. He was referring to a paper a few years back that showed a correlation between a country’s Nobel Laureates and its chocolate consumption. (The Swiss are leaders in both categories.)

Allison Reinsvold from the University of Notre Dame was one of the young researchers invited to Lindau. She said that the Laureates she met had different approaches to science, but “they all seemed to have taken time to step back and ask what are the big problems.” Her experience at Lindau gave her a greater appreciation of the Laureates’ achievements. “You realize the amount of guts and luck it takes to get the Nobel Prize,” she said.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics based in Lyon, France.