Electrons Crystallize and Melt

The word “crystal” usually refers to atoms arranged in a lattice, but Wigner crystals are made entirely of electrons. In the 23 April PRL a team describes how to make such a crystal by compressing an “electron liquid,” and how to turn the crystal back into a liquid by squeezing some more. The team’s computer models also indicate new and surprising behaviors of small electron crystals. The results suggest experiments that might allow simple and direct observation of Wigner crystallization.

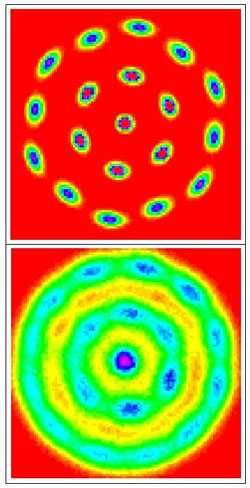

Since the mid-1930s, theorists have predicted the crystallization of electrons. If a small number of electrons are restricted to a plane, put into a liquid-like state, and squeezed, they arrange themselves into the lowest energy configuration possible–a series of concentric rings. Each electron inhabits only a small region of a ring, and this bull’s-eye pattern is called a Wigner crystal. Only a handful of difficult experiments have shown indirect evidence of this phenomenon. To help experimentalists come up with simpler and more direct methods, theorists try to characterize the conditions that lead to crystallization.

A Wigner crystal is difficult to model because it is governed by both Coulomb repulsion and quantum mechanics. To describe the crystal, theorists must calculate the very strong repulsions each electron feels from all the others. In addition, they must consider the electrons not as particles, but as quantum mechanical waves.

Michael Bonitz, of the University of Rostock in Germany, and his team used a recently developed model that includes both Coulomb and quantum effects. The group analyzed random electron arrangements, and then systematically narrowed their search until they arrived at the configuration with the lowest possible energy. They performed this simulation at a number of different pressures and temperatures, and found the precise points at which Wigner crystals formed.

The results were surprising, says Bonitz. A crystal forms when electrons are tightly compressed, but if they are squeezed too tightly, the crystal dissolves in two phases. First, the electron wave functions in the rings begin to overlap, causing the rings to spin. Then the rings themselves meld into a so-called quantum liquid. The researchers also found that the stability of a Wigner crystal depends on the number of electrons it contains. Certain numbers of electrons arrange themselves in highly symmetric rings that have melting points thousands of times higher than others.

Because this new technique is so accurate, it may provide clues for how to build a Wigner crystal, because it gives the precise conditions required. “Although it’s theory, it perhaps points a way to a realizable experiment,” says George Bertsch of the University of Washington. “The important thing,” says Bonitz, “is that we now have a complete picture that unites the classical liquid state with the quantum.”

–Geoff Brumfiel

More Information

Bonitz’s home page (click on the Wigner crystal image for description of this research)