Simple Model for Linear Magnetoresistance

Applying a magnetic field to a conductor causes its electrical resistance to increase. In certain materials, like topological insulators and graphene, this magnetoresistance obeys a unique linear behavior that could prove useful in magnetic sensors. Previous explanations of this linear effect have been based on complex models involving “massless” electrons or lattice defects. New experiments with a semiconductor quantum well suggest that linear magnetoresistance may have a simpler origin—variations in charge carrier density.

“Common” magnetoresistance—observed in most metals and semiconductors—depends quadratically on the applied magnetic field ( ). However, novel materials can exhibit a linear dependence ( ), which extends to very high field strengths. Some theories have tried explaining this linear magnetoresistance by relating it to complicated band structures that lead to electrons acting as if they had zero mass. Other models peg the magnetic response to defects or other disorder in the lattice.

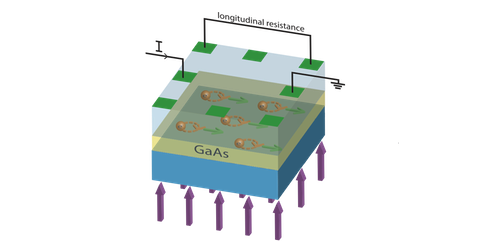

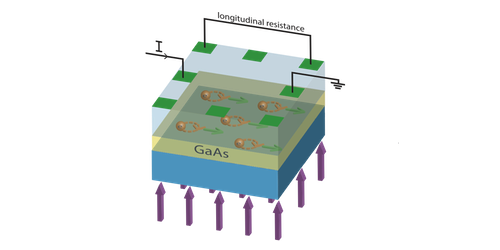

If these models were correct, then linear magnetoresistance should not be seen in any electronically simple, clean material. Thomas Khouri, from Radboud University in the Netherlands, and his colleagues have produced such a counter-example. Their semiconductor quantum well is a near defect-free, nanometer-thick slab of gallium arsenide, in which the electrons behave like normal massive particles. The team applied a magnetic field perpendicular to the well’s planar surface. As the field was ramped up to 33 T, the resistance increased linearly, reaching a maximum value 10 million times greater than the zero-field resistance. The data agree with a model that relates resistance to changes in the transverse (Hall) voltage caused by small variations or fluctuations in the charge density. Such density gradients result from microscopic inhomogeneities that are almost inevitable with modern layer-growth techniques.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics located in Lyon, France.