How stable are the heaviest nuclei?

Protons and neutrons form shell structures in a nucleus similar in some ways to those observed in the filling of electron energy levels in an atom; in particular, as shells fill up and become closed, the nucleus becomes more stable (yielding a “magic number” of nucleons). For heavy nuclei, shell effects play an important role in determining fusion reaction probabilities and fission fragmentation patterns as long as the excitation energy is not too high. Driven by theoretical predictions of new nuclear shell closures in the atomic number range of (depending upon model) researchers in heavy-ion physics and chemistry have made great progress in recent years [1]. Accelerator production techniques have now extended the periodic table to [2]. In companion studies, “one atom at a time” chemistry is being employed to establish the chemical families for new elements and explore relativistic effects in atomic structure. For the heaviest elements, electrons moving with relativistic velocities can modify the level structure and chemical behavior of an element.

However, for the synthesis technique that is commonly used (fusion of a heavy target nucleus with a heavy-ion projectile) the net production probability decreases approximately one order of magnitude for each two units of increase in atomic number as the overwhelming bulk of the nuclei produced fission into much lighter products. For the nuclei of atomic number 118 that survive fission, the cross section is (picobarn). This corresponds to a nuclear reaction probability that of normal nuclear reaction probabilities and means that with present accelerator capabilities, weeks or months of accelerator time are required to produce a few atoms. Understanding fission decay processes in these heavy nuclei can provide new guidance for fusion-based synthesis of heavier and heavier elements in the periodic table.

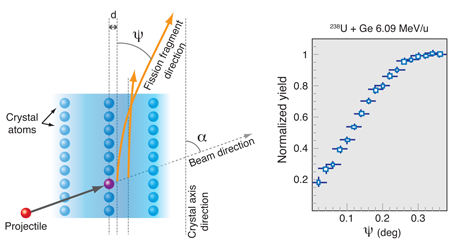

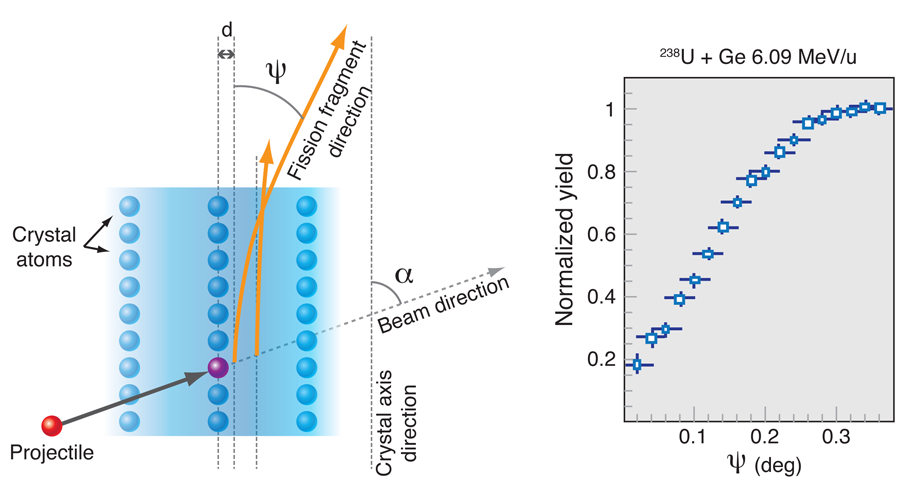

Now, Maurice Morjean and his collaborators at GANIL in France report in Physical Review Letters very precise crystal blocking experiments (Fig. 1) to measure fission decay lifetimes for nuclei in the range [3]. The authors observed fission deexcitation of excited compound nuclei formed in fusion reactions involving , , and . Their experiment combines a fission-fragment channeling measurement with a careful characterization of reaction mechanisms using the GANIL detector system INDRA that collects emitted light particles and fragments over [4]. Long tails on the decay time distributions, extending well beyond (1 attosecond), indicate long fission delays resulting from relatively high fission barriers in the region of atomic number 120 and 124. Furthermore, the fission is asymmetric, reflecting the restoration of significant shell effects as the excited compound nuclei formed in the fusion reaction cool down. These results provide very strong evidence for shell closure in the region, a feature seen in full microscopic calculations [5]. In contrast, for , the delay times are much shorter close to or below the sensitivity limit of the experiment, suggesting that shells are not being closed.

The blocking technique requires a precise measurement of the fragment angular distribution relative to the crystal axis (Fig. 1, left). Coupling this with a detector such as INDRA provides high statistics and, more importantly, allows selection of fragments from complete fusion reactions. Blocking in the atomic plane leads to shadowing of a detector oriented perpendicular to the crystal axis. Channeling between crystal planes allows the fragments to escape the crystal with very small energy losses. In the shadow realm a characteristic blocking dip (Fig. 1, right) is observed with a minimum precisely in the direction of the crystal axis. Due to its geometrical origin this dip would reach its minimum possible value for perfect crystals and experimental conditions. In practice the dips are filled and broadened due to crystal defects and radiation damage or to experimental conditions such as beam size, determination of the axis direction of the crystal, and so forth. The GANIL group has carried out extensive Monte Carlo simulations to evaluate the consequences of these effects. The minimum time which can be measured in this technique is determined by the thermal vibrations in the crystal and is . Fission times much longer than this are expected only if the (shell induced) fission barriers in these very heavy nuclei are relatively large. The derivation of more detail on the time distributions is possible but has some model dependence.

Extension of these studies over a broader range of atomic number, neutron number, and temperature should provide a wealth of new information on the shell gaps in the super-heavy element region and pinpoint the location of both spherical and possibly deformed shell closures. In addition, the relative slowness of the fission process for these very heavy nuclei may allow even modestly heated nuclei to assume exotic equilibrium shapes that manifest the nature of the underlying potential energy surface. A number of macroscopic and microscopic models suggest that nuclei in this mass range may assume very exotic Coulomb driven forms, i.e., extended linear, toroidal, or bubble-like shapes. Several calculations indicate that the nucleus , is doubly magic and has a semibubble character. The deexcitation of such nuclei may also be quite exotic, for example, fragmentation into multiple, possibly similar-mass, pieces reflecting Raleigh instabilities. Some calculations also suggest that nuclei of with low excitation energies may exist for very long times.

References

- P. Armbruster, Rep. Prog. Phys. 62, 465

- Y. T. Oganessian et al., Phys. Rev. C 74, 044602 (2006)

- M. Morjean et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 072701 (2008)

- Website for GANIL and the INDRA detector: http://infodan.in2p3.fr/indra/

- M. Bender, K. Rutz, P-G. Reinhard, J. A. Maruhn, and W. Greiner, Phys. Rev. C 60, 034304 (1999)

- M. Morjean et al., Eur. Phys. J. D 45, 27 (2007)