A Doubly Charming Particle

The discovery of new particles, from the Higgs boson to the pentaquark, usually comes highly anticipated, following lengthy experimental campaigns that go after predictions of the standard model of particle physics. These discoveries, however, do much more than validate the standard model. They also deepen our understanding of the fundamental forces that hold subatomic particles together. The new detection by CERN’s Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) Collaboration of a doubly charmed baryon called the Ξ++cc is no exception [1]. While the existence of this particle was expected, the finding is the first high-precision observation of a baryon containing two heavy quarks, and it will provide researchers with a unique system for testing quantum chromodynamics (QCD), the theory that describes the strong interaction.

The Ξ++cc resembles in many respects a conventional baryon such as the proton. Like the proton, the Ξ++cc particle is composed of three quarks bound together by gluons. The major difference comes from the particular types of quarks that make up the particle. Quarks come in light (up, down, and strange) and heavy (charm, top, and bottom) varieties. The proton is composed of light quarks only: two up quarks and one down quark, and most previously observed baryons contain at most one heavy quark. The Ξ++cc thus belongs to a special class of baryons made of two heavy quarks (charm) and one up quark.

The charm—the third heaviest quark of the six known flavors—is about 40% heavier than the proton. It behaves quite differently than light quarks. Inside hadrons (bound states of quarks and gluons), light quarks are continuously zipping by, and light quark-antiquark pairs are constantly being created. By contrast, the charm quarks are nearly static and act as a center of gravity for the hadron, playing a role reminiscent of that of the Sun in the Solar System.

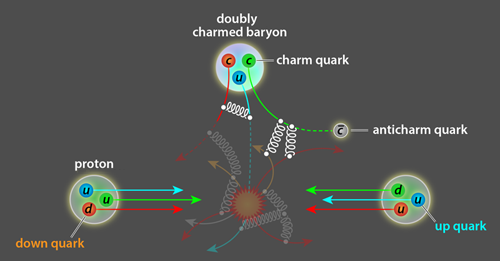

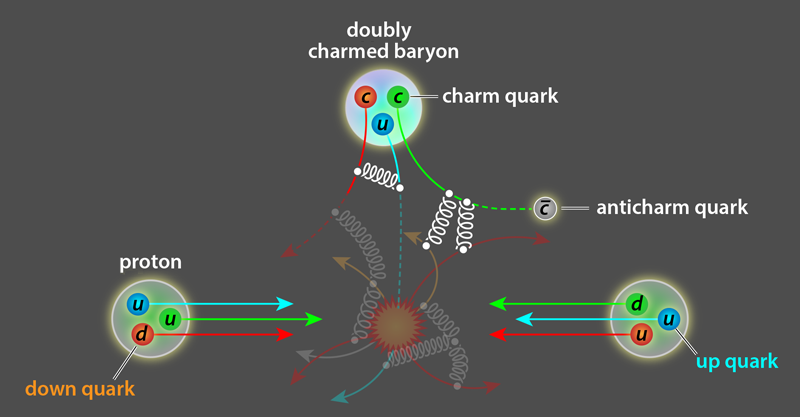

Researchers produce charm quarks in high-energy reactions, such as those triggered by the proton-proton collisions at the LHC. In such reactions, charm quarks are primarily generated together with their anticharm partners. To form a doubly charmed baryon, two of these charm-anticharm pairs must be produced simultaneously. The two charm quarks must then meet in the sea of quarks and gluons emerging from the collisions and join a light quark to form the Ξ++cc baryon (see Fig. 1). The complexity of this reaction—in conjunction with the relatively low numbers of charm quarks created in such reactions and the short lifetime of the Ξ++cc(the particle lives for approximately 10−13 s)—explains why it has taken so long to observe this particle.

The discovery of the Ξ++cc comes from data collected by the LHCb Collaboration in 2016 during the latest run of the LHC. To detect the Ξ++cc, the team sifted through signals from the many more common particles produced by proton-proton collisions. They searched for Ξ++ccsignatures from daughter particles (such as other baryons, pions, and kaons) produced by the fast Ξ++cc decay. The collaboration was able to observe an unprecedented number of events associated with the Ξ++cc particle decay, providing compelling statistical evidence for the particle’s existence and determining its mass (3621 MeV∕c2) with high precision.

The Ξ++cc fits quite naturally in our understanding, based on QCD, of the possible arrangements of quarks inside hadrons [2]. QCD foresees that baryons can be composed of any combination of three quarks, regardless of the flavor of the quarks. It also predicts a large family of doubly charmed baryons of which the Ξ++cc is one of the least energetic members.

The result, however, also raises important questions about a related baryon called the Ξ+cc, whose existence is also predicted by QCD. The Ξ+cc has the same quark composition as the Ξ++cc, except for the replacement of an up quark with a down quark. Since these two quarks have nearly identical masses, the two doubly charmed baryons should also have approximately the same mass. The near mass-degeneracy of hadrons upon the interchange of up and down quarks is called isospin symmetry—a concept first introduced to explain the small difference in proton and neutron masses. The Ξ+cc is the isospin partner of the Ξ++cc.

In 2002, Fermilab researchers reported the first observation of the Ξ+cc [3], with an inferred mass of approximately 3520 MeV∕c2. This ignited a flurry of theoretical studies aiming to confirm this value directly from QCD. Using a nonperturbative approach called lattice QCD [4], such studies calculated the expected Ξ+cc mass, assuming, for simplicity, equal masses for the up and down quarks (such calculations, in other words, would apply to both the Ξ+cc and the Ξ++cc). But the predictions from these studies were inconsistent with the measured mass of the putative Ξ+cc particle, suggesting that it should be 50 to 100 MeV∕c2 heavier than observed [5, 6]. The same inconsistency was also found by results from approximate models that retain the gross features of QCD [7].

The LHCb’s detection of the Ξ++cc has now resolved this conundrum: The previous theoretical studies had accurately predicted the mass of the Ξ++cc. In line with the recent trend in the field, this agreement provides yet another confirmation that we are entering an era where the physics of hadrons can be accurately predicted from QCD. Today, theory and experiments are almost perfectly aligned in this sector of physics, with the notable exception of the Ξ+cc.

What could be the origin of this unprecedented mass difference (100 MeV∕c2) for an isospin pair? Could it be explained by some unexpected effect caused by the small but nonzero mass difference between the up and down quarks? Or could it be due to the fact that the two baryons have different electric charges? There is already convincing theoretical evidence that these effects cannot lead to such a large difference [8]. Further research will be needed to confirm the 2002 observation of the Ξ+cc and precisely characterize its mass. If the energy gap between these two isospin partners is confirmed to be about 100 MeV∕c2, we will need to rethink our theoretical frameworks. It is thus of utmost importance that experiments promptly resolve this puzzle.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

References

- R. Aaij et al. (LHCb Collaboration), “Observation of the Doubly Charmed Baryon Ξ++cc,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 119, 112001 (2017).

- M. Gell-Mann, “A Schematic Model of Baryons and Mesons,” Phys. Lett. 8, 214 (1964).

- M. Mattson et al. (SELEX Collaboration), “First Observation of the Doubly Charmed Baryon Ξ+cc,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 89, 112001 (2002).

- K. G. Wilson, “Confinement of Quarks,” Phys. Rev. D 10, 2445 (1974).

- C. Alexandrou and C. Kallidonis, “Low-Lying Baryon Masses Using Nf=2 Twisted Mass Clover-Improved Fermions Directly at the Physical Pion Mass,” Phys. Rev. D 96, 034511 (2017).

- Z. S. Brown, W. Detmold, S. Meinel, and K. Orginos, “Charmed Bottom Baryon Spectroscopy from Lattice QCD,” Phys. Rev. D 90, 094507 (2014).

- M. Karliner and J. L. Rosner, “Baryons with Two Heavy Quarks: Masses, Production, Decays, and Detection,” Phys. Rev. D 90, 094007 (2014).

- S. Borsanyi et al., “Ab Initio Calculation of the Neutron-Proton Mass Difference,” Science 347, 1452 (2015).