Weak Lensing Becomes a High-Precision Survey Science

Over the last decades, scientists have built a paradigm cosmological model, based on the premises of general relativity, known as the ΛCDM model. This model has successfully explained many aspects of the Universe’s evolution from a homogeneous primeval soup to the inhomogeneous Universe of planets, stars, and galaxies that we see today. The ΛCDM model is, however, at odds with the minimal standard model of particle physics, which cannot explain the two main ingredients of ΛCDM cosmology: the cold dark matter (CDM) that represents approximately 85% of all matter in the Universe and the cosmological constant ( Λ), or dark energy, that drives the Universe’s accelerated expansion.

One potential way to sort out the nature of dark matter and dark energy exploits an effect called weak gravitational lensing—a subtle bending of light induced by the presence of matter. Measurements of this effect, however, have proven challenging and so far have delivered less information than many physicists had hoped for. In a series of articles [1], the Dark Energy Survey (DES) now reports remarkable progress in the field. Analyzing data from its first year of operation, the DES has combined weak lensing and galaxy clustering observations to derive new constraints on cosmological parameters. The results suggest that we have reached an era in which weak gravitational lensing has become a systematic, high-precision technique for probing the Universe, on par with other well-established techniques, such as those based on observations of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) and on measurements of baryonic acoustic oscillations (BAO).

Gravitational lensing is a consequence of the curvature of spacetime induced by mass. As light travels toward Earth from distant galaxies, it passes through clumps of matter that distort the light’s path. If lensing is strong, this distortion can dramatically stretch the images of the galaxies into long arcs. But in most situations, lensing is weak and causes subtler deformations—think of the distortions of images printed on a T-shirt that’s slightly stretched. Galaxies in the same part of the sky, whose light travels a similar path to us, are subjected to similar stretching, making them appear “aligned”—an effect known as cosmic shear. By quantifying the alignment of “background” galaxies, weak-lensing measurements derive information on the “foreground” mass that causes the distortions. Since dark matter constitutes the majority of matter, weak gravitational lensing largely probes dark matter.

The potential of the technique has been known for decades [2]. Initially, however, researchers didn’t realize how difficult it would be to measure the tiny signal due to weak lensing and to isolate it from myriad other effects that cause similar distortions. Most importantly, for ground-based observations, the light reaching the telescope goes through Earth’s atmosphere. Atmospheric conditions, optical imperfections of the telescope, or simply inadequate data reduction techniques can blur or distort the images of individual objects. If such effects are coherent across the telescope’s field of view, they can lead to subtle alignments that can be misinterpreted as consequences of weak lensing. Moreover, most galaxies are elliptical to start with, and these ellipticities can be aligned for astrophysical reasons unrelated to weak lensing.

Despite these difficulties, several pioneering efforts established the feasibility of weak gravitational lensing. In 2000, several groups reported the first detections of cosmic shear [3]. These were followed by 15 years of important advances, such as those obtained using data from the Sloan Digital Sky Survey [4], the Kilo-Degree Survey [5], and the Hyper Suprime-Cam Subaru Strategic Survey [6].

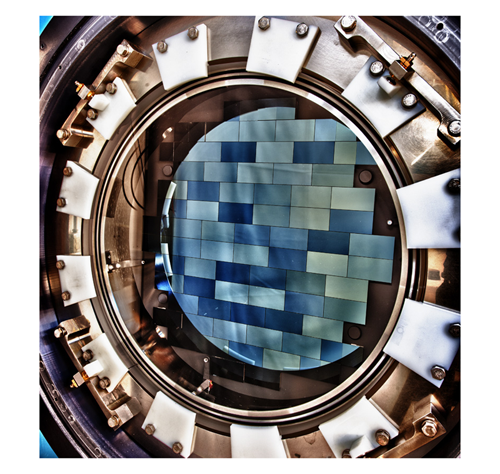

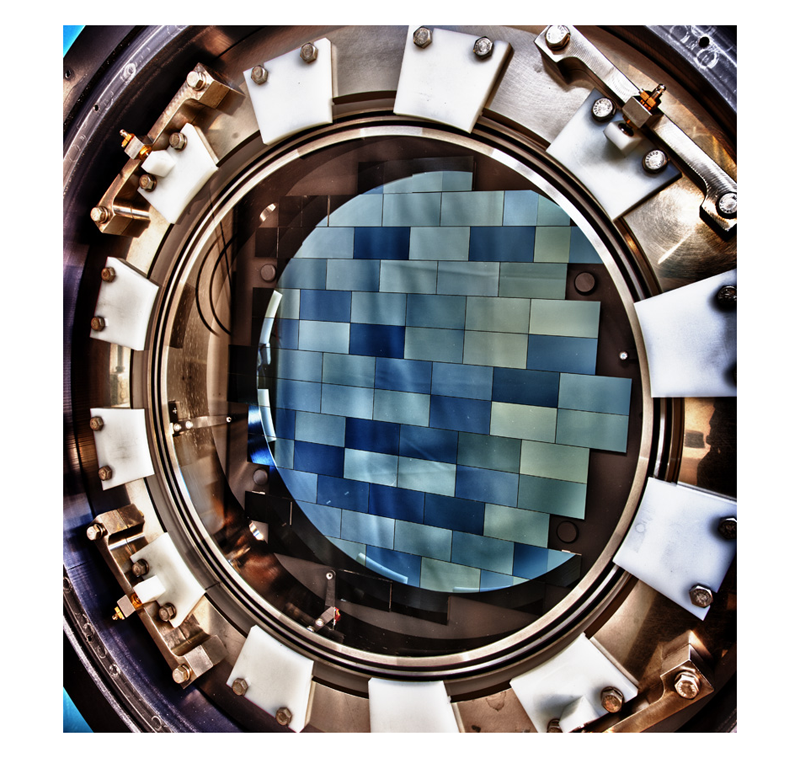

However, the new DES results mark an important milestone in terms of accuracy and breadth of analysis. Two main factors enabled these results. The first was the use of the Dark Energy Camera (DECam), a sensitive detector, custom-designed for weak-lensing measurements (Fig. 1), which was mounted on the 4-m-aperture Victor M. Blanco telescope in Chile, where DES has a generous allocation of observing time. The second factor was the size of the collaboration—more on the scale of a particle-physics collaboration than an astrophysics one. This resource allowed DES to dedicate unprecedented attention to data analysis. For example, two independent weak-lensing “pipelines” performed an important cross check of the results. [7]

As reported in the latest crop of DES papers, the collaboration mapped out the dark matter in a patch of sky spanning 1321 deg2, or about 3% of the full sky. They performed this mapping using two independent approaches. The first provided a direct probe of dark matter by measuring the cosmic shear caused by foreground dark matter on 26 million background galaxies. The second approach entailed measuring the correlation between galaxy positions and cosmic shear and the cross correlation between galaxy positions. Comparing these correlations allowed the underlying dark matter distribution to be inferred. The two approaches led to the same results, providing a compelling consistency check on the weak-lensing dark matter map.

The collaboration used the weak-lensing result to derive constraints on a number of cosmological parameters. In particular, they combined their data with data from other cosmological probes (such as CMB, BAO, and Type 1a supernovae) to derive the tightest constraints to date on the dark energy equation-of-state parameter (w), defined as the ratio of the pressure of the dark energy to its density. This parameter is related to the rate at which the density of dark energy evolves. The data indicate that w is equal to −1, within an experimental accuracy of a few percentage points. Such a value supports a picture in which dark energy is unchanging and equal to the inert energy of the vacuum—Einstein’s cosmological constant—rather than a more dynamical component, which many theorists had hoped for.

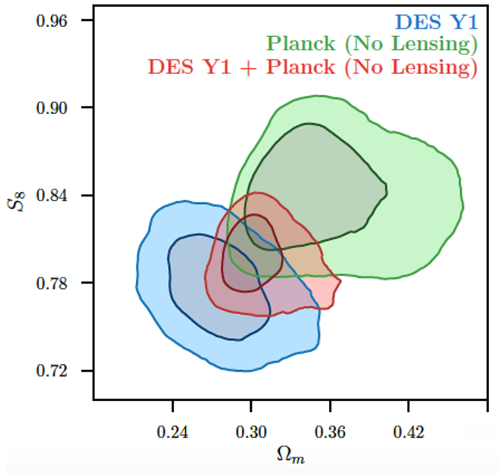

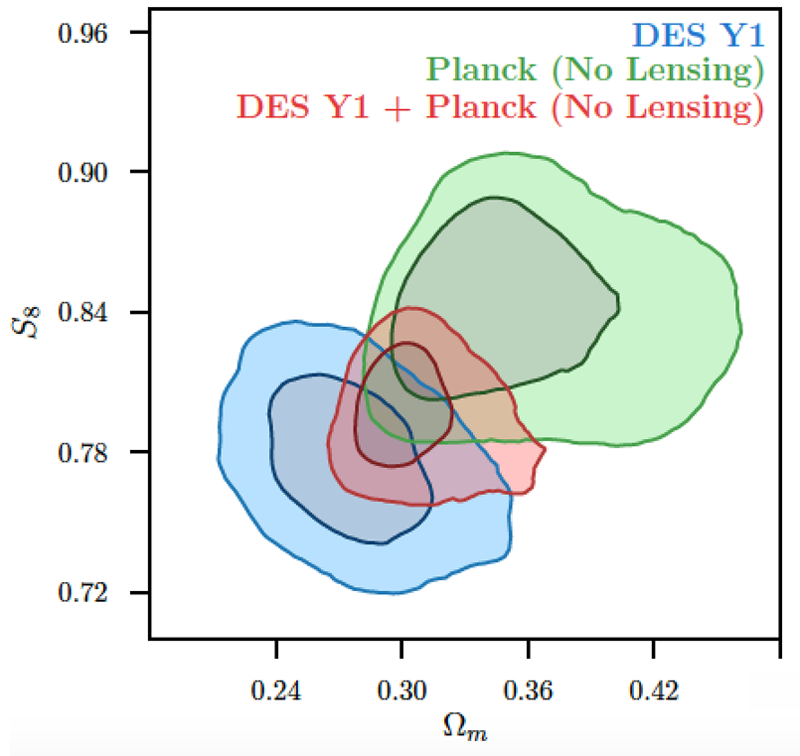

One of the most important aspects of the DES reports is the comparison with the most recent CMB measurements from the Planck satellite mission [8]. The CMB is the radiation that was left over when light decoupled from matter around 380,000 years after the big bang, so Planck probes the Universe at high redshift ( z∼1100). The DES data, on the other hand, concern much more recent times, at redshifts between 0.2 and 1.3. To check whether Planck and DES are consistent, the CMB-constrained parameters need to be extrapolated across cosmic history (from z∼1100 to z∼1) using the standard cosmological model. Within the experimental uncertainties, this extrapolation shows good agreement (Fig. 2), thus confirming the standard cosmological model’s predictive power across cosmic ages. While this success has to be cherished, everyone also silently hopes that experimenters will eventually find some breaches in the ΛCDM model, which could provide fresh hints as to what dark matter and dark energy are.

The next few years will certainly be exciting for the field. DES already has five years of data in the bag and will soon release the analysis of their three-year results. Ultimately, DES will map 5000 deg2, or one eighth of the full sky. The DES results are also very encouraging in view of the Large Synoptic Survey Telescope (LSST)—a telescope derived from the early concept of a “dark matter telescope” proposed in 1996. LSST should become operational in 2022, and it will survey almost the entire southern sky. Within this context, we can be hopeful that weak-lensing measurements will provide important insights into the most pressing open questions of cosmology.

This research is published in Physical Review D.

References

- T. M. C. Abbot et al., “Dark Energy Survey year 1 results: Cosmological constraints from galaxy clustering and weak lensing,” Phys. Rev. D 98, 043526 (2018); J. Elvin-Poole et al., “Dark Energy Survey year 1 results: Galaxy clustering for combined probes,” 98, 042006 (2018); J. Prat et al., “Dark Energy Survey year 1 results: Galaxy-galaxy lensing,” 98, 042005 (2018); M. A. Troxel et al., “Dark Energy Survey Year 1 results: Cosmological constraints from cosmic shear,” 98, 043528 (2018).

- A. Albrecht et al., “Report of the Dark Energy Task Force,” arXiv:0609591.

- D. M. Wittman et al., “Detection of weak gravitational lensing distortions of distant galaxies by cosmic dark matter at large scales,” Nature 405, 143 (2000); D. J. Bacon et al., “Detection of weak gravitational lensing by large-scale structure,” Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 318, 625 (2000); N. Kaiser, G. Wilson, and G. A. Luppino, “Large-Scale Cosmic Shear Measurements,” arXiv:0003338; L. Van Waerbeke et al., “Detection of correlated galaxy ellipticities from CFHT data: First evidence for gravitational lensing by large-scale structures,” Astron. Astrophys. 358, No. 30, 2000.

- H. Lin et al., “The SDSS Co-add: Cosmic shear measurement,” Astrophys. J. 761, 15 (2012).

- F. Köhlinger et al., “KiDS-450: the tomographic weak lensing power spectrum and constraints on cosmological parameters,” Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 471, 4412 (2017).

- R. Mandelbaum et al., “The first-year shear catalog of the Subaru Hyper Suprime-Cam Subaru Strategic Program Survey,” Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 70, S25 (2017).

- It’s worth mentioning that the data analysis used “blinding,” a protocol in which the people carrying out the analysis cannot see the final results, so as to eliminate possible biases towards specific results..

- N. Aghanim et al. (Planck Collaboration), “Planck 2018 results. VI. Cosmological parameters,” arXiv:1807.06209.