Astronomy Students Not Learning the Basics

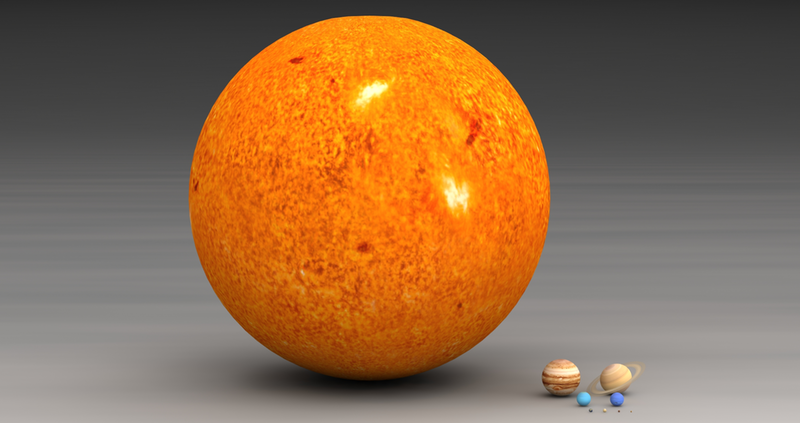

Are stars bigger than planets and galaxies bigger than solar systems? A study published in Physical Review Physics Education Research shows that both astronomy students and future teachers struggle with these seemingly basic questions. The researchers found that a significant proportion of study participants were unable to identify the correct size ordering of these objects. They also found common misconceptions about distance scales in astronomy. The team suspects that these mistakes arise from the difficulty of comprehending astronomical scales, which could make them hard to dislodge simply by supplying factual information.

As teachers and education researchers have long known, routine testing of students can fail to uncover profound misunderstandings about what seem like foundational principles in a subject. Even students who perform well on astronomy tests may hold misunderstandings about basic facts, such as the shapes of planetary orbits or the approximate Earth-Moon distance relative to the objects’ sizes [1].

Astrophysicist Vinesh Maguire Rajpaul of the University of Cambridge, UK, and colleagues have delved into some of these deep-seated misconceptions. They tested the astronomical knowledge of Norwegian middle school pupils (grades 8–10) through questionnaires asking them to rank the sizes of the Galaxy, the Solar System, stars, planets, and the Universe, and requesting simple explanations of each. The students, who were tested before and after having instruction in astronomy, also ranked the distances from Earth of ten astronomical entities, such as the Sun and the center of the Milky Way. Rajpaul says that, while previous studies have also probed students’ perceptions of astronomical sizes and distances, the new tests were more comprehensive and used analytical tools “that allow a wealth of information to be straightforwardly extracted and summarized.”

In the most common misunderstanding of relative size, nearly half of the middle school students believed that planets are larger than stars. And about 60% thought that the North Star lies within our Solar System. Perhaps still more worryingly, astronomy instruction didn’t appear to correct these mistakes.

Rajpaul and his colleagues say that misconceptions about size seem to reflect deeper misunderstandings. “We found that if students demonstrate a basic understanding of two different astronomical objects by giving basic, one-sentence explanations of them, they are almost guaranteed to be able to rank them correctly,” says coauthor Christine Lindstrøm of Oslo Metropolitan University (OMU) in Norway.

The researchers also tested teacher trainees at OMU, the largest teacher-training center in Norway. All participants had taken some courses in physics and astronomy, and they were more knowledgeable than the middle schoolers—87% knew that the Sun is larger than the Earth, for example. But there were still some significant misconceptions, with a quarter thinking that the North Star is in our Solar System.

The researchers speculate that these misconceptions might arise because astronomical scales and objects are so remote from everyday experience and therefore are hard to intuit. Stars appear as pinpricks of light, whereas we are used to seeing planets represented as entire other worlds and have experienced the vastness of the Earth for ourselves. If so, these errors may be hard to displace simply by delivering factual information, Rajpaul and colleagues say, because they are caused by deeper cognitive factors. They suggest that experience in planetaria might help because presentations could, for example, zoom in on stars and planets in a way that shows differences in size. The immersive experience of virtual reality might work even better, Rajpaul suggests.

The findings add to our understanding of where learning goes awry, says astronomy education specialist Tony Lelliott of the University of the Witwatersrand in South Africa. But he points out that in addition to questionnaires, such studies should include interviews, “to really find out how people think.”

Astrophysicist Priyamvada Natarajan of Yale University, who talks and writes extensively on her subject for the public, is unsurprised by these misconceptions. “It’s only after familiarity from dealing repeatedly with these scales and numbers that one can begin to have a grasp on them.”

Lindstrøm thinks that the findings may have implications for teaching in other fields of science where scales elude intuition; teachers in these fields should be aware of the potential for similar misconceptions. “We hope our work can carry over to microscopic scales, too, as well as to other scales outside of human experience, such as energy scales in various branches of physics.”

This research is published in Physical Review Physics Education Research.

–Philip Ball

Philip Ball is a freelance science writer in London. His latest book is How Life Works (Picador, 2024).

References

- P. M. Sadler, Ph.D. thesis, Harvard University, Cambridge, MA (1992); M. H. Schneps and P. M. Sadler, A Private Universe, documentary film for the Harvard Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (1989).