So, You Think You Discovered a New State of Matter?

“No, you probably have not discovered a new state of matter,” is what I tell myself every time a student in my lab brings me a peculiar piece of data. I try to remain skeptical and first assume that the data come from a glitch, a coincidence, or some other triviality. But even then, I can’t help but be hopeful; maybe we have found something new.

It is human nature to want miracles. But miracles don’t happen. And in physics, as in many areas of life, the desire for them can cloud us from seeing reality and block us from asking the right questions. Personally, I only get a kick from true discoveries—fooling myself with mirage breakthroughs does not cut it, as I know that they will eventually fall apart. I encourage other physicists to keep this in mind, particularly condensed-matter physicists searching for new states of matter, where, in my view, claims are often made too quickly.

Gas, liquid, and solid are the three main states of matter. Physicists, however, distinguish many more. For example, within solids there are electrically conducting states, insulating states, and superconducting states, among others.

Discovering an entirely new state of matter is a big prize. Many physicists, including myself, are actively working on it. One place we are looking for them is in the mesoscopic regime. Mesoscopic systems are ones that sit between the microscopic quantum world and the macroscopic classical world. To a large extent, research on these systems laid the groundwork for quantum computers. But it’s the possibility of finding matter in exotic quantum states that currently has the field’s attention.

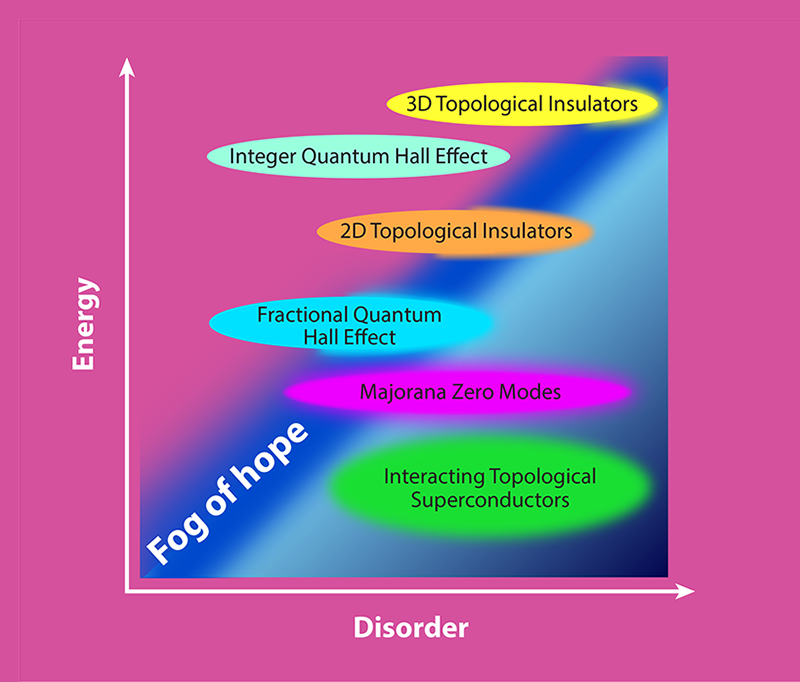

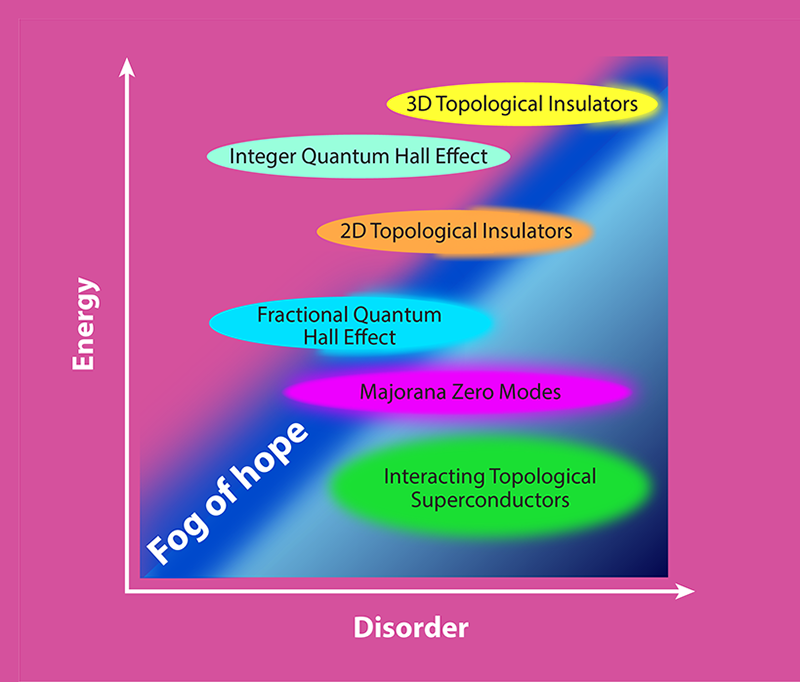

And there are plenty of opportunities for that. The “meso” regime is like a newly discovered coral reef in the ocean—it may be rich with previously unseen creatures. And indeed, in our explorations of this world at the quantum frontier, we are finding hints of new behaviors. One class of these behaviors is termed “topological,” and an example of a topological state is a topological insulator. When materials exhibit this state, their surface stays conducting no matter how it is shaped, while their inside is insulating.

Another example of a heavily investigated topological state is topological superconductivity, which is a state that I am interested in. Topological superconductivity is tricky to describe, but loosely speaking, materials that exhibit this behavior have insides that superconduct and surfaces that host exotic quantum states known as Majorana zero modes (MZMs). These modes are interesting as they are predicted to be distinguishable from one another, a behavior that violates a fundamental rule for all known particles in the Universe. Researchers think that these states could be exploited to make quantum computers more robust to noise.

These predictions set the stakes high for the experimental confirmation of MZMs, and the search for them is now widespread, encompassing disparate systems from nanowires (my focus) to chains of magnetic atoms to spin liquids. In nanowires, the predicted MZM signature is a peak in the wire’s tunneling conductance when the wire is connected in a transistor-like electrical circuit. Find that peak, and you’ll discover MZMs. It sounds simple, except that the MZM signal can be masked by similar peaks from non-Majorana, nontopological states.

That dubiousness is why researchers in the field should question their data first and make tentative claims of a discovery only after ruling out other explanations. Extraordinary claims require compelling proof: there is no room for unexplained miracles within the scientific method. If we think we have made a major discovery, we should first examine our data for internal consistency and tie up any loose ends. If, after that, we can honestly say to ourselves—and to our colleagues—that our claim may still be justified, perhaps with caveats, we can cautiously announce it. But even then, we should carefully present all possible explanations. Journals, referees, peers, and news organizations should take those alternative possibilities into account when interpreting or reporting on new results.

For MZMs, I am hopeful that their discovery will soon occur, either in current systems or in future ones. Cleaner materials—higher-purity nanowires, for example—will likely have clearer MZM signals, and there may be better, less-explored systems to probe. But until we can present incontrovertible evidence, it is important that we all keep reminding ourselves that “no, we probably have not discovered a new state of matter.”