Multiferroic Propellers

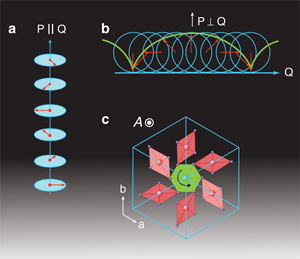

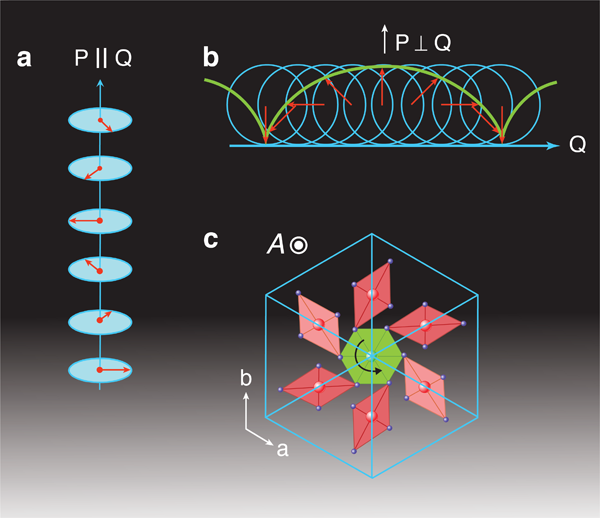

Control of spin ordering in magnetic insulators with an applied electric field (also known as the magnetoelectric effect) can significantly reduce the power consumption of memory devices, but with no mobile charges present, it would seem to be an impossible task. Encouragingly, it was recently discovered that some magnetic orders induce an electric polarization, which couples spins to electric field. So far, the electrical polarization in such magnetic ferroelectrics (also called multiferroics) tends to be small and the Néel magnetic transition temperature is usually well below liquid nitrogen temperature. Now, however, Roger Johnson and co-workers at the University of Oxford, UK, with collaborators in France, report in Physical Review Letters on achieving giant polarization in CaMn7O12. The measured polarization is the highest measured magnetically induced polarization, persisting up to a Néel temperature of 90K. Remarkably, this polarization appears to be induced by a long-period helicoidal (or proper-screw) spin spiral [see Fig. 1(a)], in which spins rotate around the spiral wave vector [1]. This discovery represents an important development for the field of magnetic ferroelectrics, as large polarization is crucial for electric manipulation of spins. It confirms earlier estimates of polarization from studies of polycrystalline samples [2].

The most ubiquitous spin ordering that gives rise to ferroelectricity is the cycloidal spiral, in which spins rotate around an axis normal to the spiral wave vector. A cycloid—a curve traced by a point on the rim of a wheel rolling over a flat surface—is asymmetric along the direction normal to both the direction of motion and the wheel axis, and this is also the direction of the electric polarization induced by a spin cycloid [see Fig. 1(b)]. By contrast, helicoidal ferroelectrics are rare, and all materials studied so far are only weakly ferroelectric [3,4].

The clockwise or counterclockwise direction of spin rotation in the helicoidal spiral is described by a quantity called helicity. This quantity changes sign under inversion of all spatial coordinates and is the reason why, in magnets without inversion symmetry, spins often roll into a spiral. The sign of helicity is imposed by the crystal structure. The CaMn7O12 crystals are, however, symmetric under inversion, and the positive or negative helicity is chosen spontaneously at the magnetic transition point. The direction of the electric polarization, which is set at the same transition temperature as the magnetic transition temperature, is determined by the direction of spin rotation in the spiral.

One would think it is impossible to couple electric polarization to helicity because the direction of spin rotation in the helical spiral is preserved when the spiral axis is rotated, whereas the polarization vector oriented along the axis of the helix changes sign when the sample is turned around. The only way to make the electric polarization proportional to helicity is to “forbid” such crystal rotations, that is, the crystal should look different when viewed from above and from below [5]. Johnson and colleagues suggest that this can be a result of an axial lattice distortion transforming like a component of an axial vector, which remains invariant under inversion and rotations around the helical axis, but changes sign when this axis is turned around. The authors show that in CaMn7O12, the axial vector is induced by the “propellerlike” structure formed by the manganese-oxygen octahedra in each unit cell [see Fig. 1(c)]. The product of this axial vector and helicity can be linearly coupled to electric polarization. The fact that the helical spiral induces electric polarization only in axial crystals also explains why the helicoidal ferroelectrics are less common than the cycloidal ones.

But while the relation between helicity, axiality, and ferroelectricity may now be clear, why is the polarization of CaMn7O12 so much larger than other helicoidal ferroelectrics? The form of the magnetoelectric coupling for the helicoidal spiral, and the fact that it is incommensurate with the crystal lattice (the period of the helix is not a multiple of the lattice constant), points at the important role of the electron spin-orbit coupling. Due to this coupling, a pair of noncollinear spins pushes positively and negatively charged ions away from each other. The resulting electric dipole is typically rather small because the spin-orbit coupling is a weak relativistic effect for most magnetic materials, which makes one wonder why the polarization of CaMn7O12 is 5 times larger than that of TbMnO3 with a cylcoidal spiral ordering? In addition, the spin noncollinearity in CaMn7O12 is very small: the angle between neighboring spins along the helix axis is only 4 degrees.

The case is clearly not yet settled. To introduce electric dipoles, the most efficient route is by pairs of collinear spins, which requires no relativistic interactions. However, this mechanism usually only works if magnetic modulation is commensurate with the lattice and it is not effective in spirals. This suggests an alternative interpretation of the origin of ferroelectricity in CaMn7O12. It turns out that the crystal lattice of this material also shows a small periodic incommensurate modulation below 250K, and the period of the magnetic ordering appearing below 90K equals two periods of the structural modulation [6]. This situation is reminiscent of stripes—atomic-scale rivulets of charge in the Cu- O plane in high-temperature cuprate superconductors—in which the antiferromagnetic spin order changes sign when it crosses a charged stripe. Below 55K, neutron powder diffraction data indicate the existence of two different incommensurate magnetic modulations, and it turns out that the sum of their wave vectors equals the wave vector of the structural distortion. It seems this “synchronization” of structural and magnetic modulations enables the stronger nonrelativistic mechanism of magnetoelectric coupling. Further studies of magnetic states in this material are necessary to clarify the origin of its remarkably large electric polarization. However, the strong magnetoelectric coupling found in CaMn7O12 will undoubtedly stimulate the search for other axial ferroelectrics to see if they too exhibit such a large polarization.

References

- R. D. Johnson, L. C. Chapon, D. D. Khalyavin, P. Manuel, P. G. Radaelli, and C. Martin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 067201 (2012)

- G. Zhang, S. Dong, Z. Yan, Y. Guo, Q. Zhang, S. Yunoki, E. Dagotto, and J.-M. Liu, Phys. Rev. B 84, 174413 (2011)

- T. Kimura, J. C. Lashley, and A. P. Ramirez, Phys. Rev. B 73, 220401 (2006)

- M. Kenzelmann et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 267205 (2007)

- T. Arima, J. Phys. Soc. Jpn. 76, 073702 (2007)

- W. Slawinski, R. Przenioslo, I. Sosnowska, and M. Bieringer, J. Phys. Condens. Matter 22, 186001 (2010)