Water Flow Helps Cells Move

Biological cells change shape in order to move around, communicate, or sense their surroundings. Such shape changes often begin with the formation of a so-called “bleb,” a rounded protrusion of the cell membrane. Researchers generally assume that blebs form without any change in cell volume, like a water balloon that bulges in one place when squeezed elsewhere. But now Caterina La Porta of the University of Milan, Italy, and her colleagues have shown with experiments and simulations that volume changes are essential.

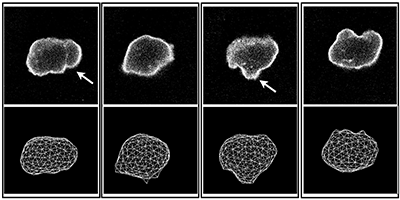

A bleb forms when the cytoskeleton—the rigid mesh structure just below the membrane—contracts, producing a membrane bulge. But there have also been indications that the process involves aquaporins, channels in the membrane that allow water to flow through. To study the role of volume changes, the researchers observed single-cell zebrafish embryos that continuously initiate and then retract blebs. The team compared normal cells with three genetically engineered mutants: cells that overproduce aquaporins (AQP +), cells that underproduce aquaporins (AQP -), and cells whose cytoskeletal contraction is inhibited (DN-ROK).

La Porta and her colleagues used fast imaging with an intense membrane dye to observe cells as they were producing and retracting blebs and processed the videos to measure the changes in volume and surface area. They found that surface and volume fluctuations were enhanced for the AQP + cells and suppressed in the AQP - and DN-ROK cells. The two suppressed cell types showed similar effects, suggesting that the water flow regulated by aquaporins is as important for blebbing as cytoskeletal contractions. The team’s numerical model supported this view, showing that the data could only be reproduced with significant membrane porosity.

–David Ehrenstein

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.