Sensing Delays Control Robot Swarming

Researchers have designed an ensemble of robots whose collective behavior can be changed from clustering to dispersive by controlling the time delay between when they receive a light signal and when they react to it. The team tested a group of small robots, each of which sends out its own light signal. These findings could be exploited in search-and-rescue missions where robots must first disperse widely to effectively search an area and then cluster together to share data.

Animals organize into flocks, swarms, and colonies, and researchers would like to understand how their collective behaviors are coordinated. Groups of autonomous robots could potentially be organized in similar ways, and whether it’s animals or robots, researchers call the individuals “autonomous agents.” Studies of these agents have largely ignored the role of sensorial delays—the time between when an agent receives a signal and when that signal is processed—or treated them as an inconvenience [1]. However, “understanding time delay in autonomous mobile individuals is crucial to understanding self-organized patterns in moving entities that sense and react to signals,” says Fernando Peruani of the University of Nice in France. Now Giovanni Volpe of Bilkent University in Turkey and Jan Wehr of the University of Arizona and their colleagues have explored using sensorial delays to modify the collective behavior of a troop of light-sensing robots.

Volpe, Wehr, and their colleagues first studied one robot in isolation. They placed a poker-chip-sized robot on the floor near a 100-watt infrared lamp. The robot’s speed was programmed to be inversely proportional to the intensity of light it measured—it slowed down when it passed near the lamp and sped up when far away. The robot was also designed to change its direction a little bit every second so that its direction was completely randomized after about 10 seconds. The researchers introduced a sensorial delay of up to 10 seconds between the time when the robot measured the light intensity and when it responded by changing speed. This delay was long enough to allow the robot to partially randomize its direction before adjusting its speed. The team also experimented with negative sensorial delays, where the robot extrapolated past light measurements to predict the future light intensity (for example, predicting continually increasing intensity when approaching the lamp).

The researchers found that applying a positive delay caused the robot to preferentially remain near the infrared lamp, while a negative delay sent it exploring regions far away. To understand these results, imagine a robot with a positive delay moving outward (away from the light). It will move slower than a robot without a delay because it’s always responding as though it’s closer to the light, receiving a stronger light signal. So it remains essentially “trapped” within the region close to the lamp if the delay is long enough. Conversely, a robot with a negative delay traveling outward will move faster than an undelayed robot, so it “escapes” the region close to the lamp.

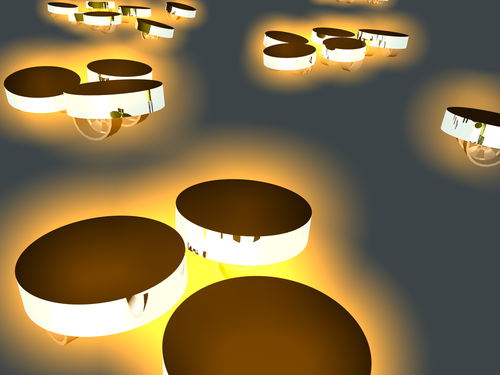

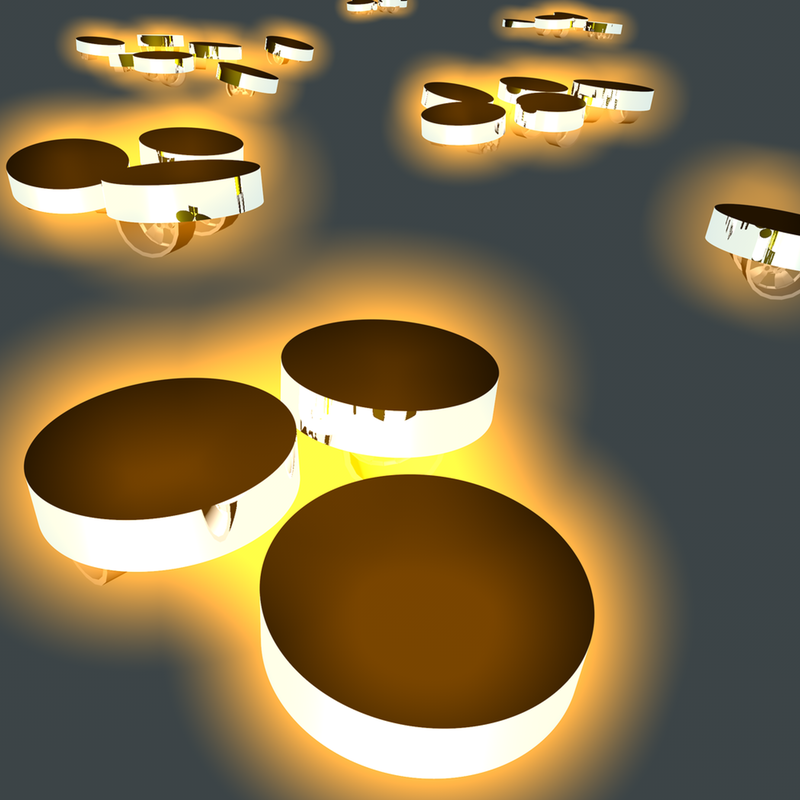

The team confirmed their results using groups of robots, each of which generated its own infrared light and sensed the light of its neighbors. With a positive sensorial delay, the robots moved toward one another and formed clusters. With a negative delay, they dispersed to seek out low-light conditions. The researchers suggest that these trends can be adjusted in real time to use autonomous robots in tasks such as search-and-rescue operations, in which both clustering and dispersion are valued. They note that any radially decaying signal—such as a chemical or acoustic one—could be used to the same effect. The team has also performed simulations showing that their results hold true for agents operating in three dimensions, such as flying drones or submarine robots.

This work “identifies a new, powerful control parameter in artificially programmed swarming,” says Hartmut Löwen, of the University of Düsseldorf in Germany. Charles Reichhardt of Los Alamos National Laboratory in New Mexico says that sensorial delays can be “harnessed to generate artificial collective behaviors in aerial drone swarms, groups of robots, self-driving vehicles, and other active systems.”

This research is published in Physical Review X.

–Katherine Kornei

Katherine Kornei is a freelance science writer in Portland, Oregon.

References

- Y. Chen, J. Lü, and X. Yu, “Robust Consensus of Multi-Agent Systems with Time-Varying Delays in Noisy Environment,” Sci. China Technol. Sci. 54, 2014 (2011).