The First Stars May Shed Light on Dark Matter

The nature of the dark matter is one of the longest-standing puzzles in cosmology. Astronomers have established that dark matter is the dominant constituent of matter in the Universe, but they are still in the dark about its identity. A possible clue may have been uncovered by recent observations of the cosmic dawn—the epoch when the first stars formed (Fig. 1). Earlier this year, researchers reported a surprisingly strong absorption signal coming from gas activated by light from the first stars [1]. Now, a series of new papers [2–5] has explored what might be inferred about dark matter from this unexpected absorption. For example, the absorption could be explained by assuming that dark matter carries a small electric charge that allows it to interact weakly with ordinary matter. On the flip side, the absorption is inconsistent with certain models that predict dark matter should annihilate with itself. Regardless of the final interpretation, the cosmic dawn has clearly opened a new path toward resolving the dark matter puzzle.

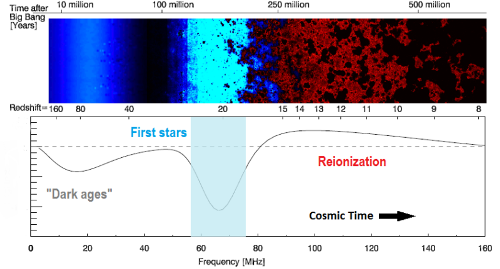

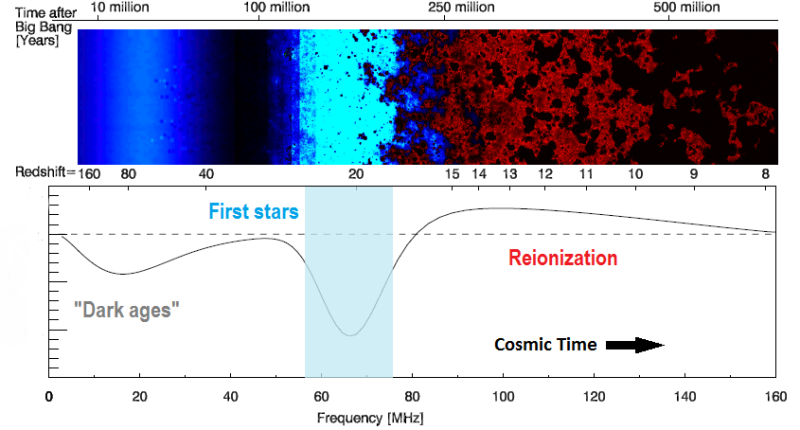

For nearly a century [6], scientists have been studying dark matter through its gravitational effects on visible matter and radiation. Those observations have confirmed that dark matter is one of the primary constituents of the Universe. The measured anisotropies of the cosmic microwave background (CMB), for example, have shown that the overall density of dark matter is about five times that of ordinary (baryonic) matter. But the anisotropies are not the only aspect of the CMB that may contain information about the matter in the Universe. The CMB light carries an imprint of hydrogen gas that it encountered along its journey—a journey that started 400,000 years after the big bang. The imprinted signal is due to absorption of CMB photons with 21-cm wavelength, corresponding to the electronic transition in hydrogen’s hyperfine levels (see Fig. 2). Because the universe is expanding, this absorption is redshifted to longer wavelengths, so that observations at a particular wavelength correspond to a specific time in the past.

Early on during the so-called “dark ages,” the absorption from hydrogen gas was minimal, as the populations in the hyperfine levels were close to thermal equilibrium with the CMB. However, the absorption is expected to have increased dramatically at the start of the cosmic dawn—about a hundred million years after the big bang. At this time, the ultraviolet radiation from the first stars began exciting the hydrogen atoms, causing the hyperfine level populations to shift in such a way that they reflected the temperature of the gas [7]. As such, the strength of the 21-cm absorption from a particular epoch depends on the corresponding gas temperature, with more absorption occurring in colder gas. According to standard cosmological models, the gas reached its lowest temperature during the cosmic dawn (after which, the gas went through “reionization” and no longer absorbed 21-cm photons from the CMB). However, interactions with dark matter could either cool or heat the hydrogen atoms from the cosmic dawn [8], producing a spectrum that differs from the expectations in Fig. 2.

Measuring the 21-cm absorption is the goal of several new and upcoming experiments. One of these, EDGES (Experiment to Detect the Global Epoch of reionization Signal) [1], has offered the first sky-averaged spectrum at wavelengths corresponding to the redshifted 21-cm line. The data revealed an absorption dip at a wavelength of 380 cm, or equivalently, at a frequency of 78 MHz. The depth of this dip implies that roughly one in six CMB photons around this frequency were absorbed by intervening hydrogen. This depth is a factor of 2 larger than the standard prediction. It is tempting to associate this unexpected cooling with some nonstandard interaction of the gas with cold dark-matter particles, but one should proceed with caution. For instance, in Ref. [9] it was argued that a new fundamental force between dark matter and baryons could explain this signal. However, having a new force of this magnitude is ruled out because, for example, it would cause stars to cool faster than observed.

By contrast, we showed in Ref. [2] that the baryons can be cooled down if a fraction of the dark-matter particles are light in mass and have an electric charge of about one millionth that of the electron. Coulomb interactions would make these minicharged dark-matter particles scatter off electrons and protons. Because the dark sector is colder than the baryonic sector, the net effect of these scatterings would be to cool the baryons. This scenario can explain the EDGES observations without introducing any new fundamental force. Asher Berlin from the SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory in California and colleagues have now considered a similar setup and found results mirroring our own [3]. They also explored ways to constrain the abundance of minicharged dark matter by imagining that these particles can annihilate into neutrinos or into other types of dark matter.

Minicharged dark matter is not ruled out by current particle physics theory, but it nonetheless is an extraordinary claim that would require extraordinary evidence. Fortunately, the proposed interactions lead to a new testable prediction for the variation across the sky of the depth of the 21-cm absorption feature at 78 MHz [10]. Similar to how the intensity of the CMB depends on the direction in which you look, the 21-cm signal is expected to have spatial fluctuations based on the relative motion between dark matter and baryons [11]. Anastasia Fialkov from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics in Massachusetts and her co-workers have now simulated multiple maps of the 21-cm signal, employing hundreds of different astrophysical models [4]. They show that adding a fifth-force interaction between dark matter and ordinary matter significantly increases the 21-cm fluctuations relative to standard predictions. Therefore, future radio interferometers, such as LOFAR and HERA, should more easily detect the 21-cm fluctuations if the EDGES result is indeed caused by dark matter carrying a small electric charge.

Even if the EDGES signal is not the result of charged dark matter, a measurement of the gas temperature during cosmic dawn can still constrain the nature of dark matter in other ways. Guido D'Amico and his colleagues from CERN in Geneva have now exploited this idea by studying how dark-matter annihilations, which are an outcome of many dark-matter models, could inject energy and heat the hydrogen [5]. They show that the EDGES observations—which imply colder-than-expected hydrogen—place the tightest constraints ever determined on dark-matter annihilations. In particular, one can rule out typical dark-matter candidates if their masses are less than ten times the proton mass, eliminating the possibility of light, WIMP-like dark matter.

The above results showcase the promise of cosmic dawn measurements for addressing the dark-matter puzzle. Even feeble dark-matter interactions—which affect the hydrogen gas by either removing or depositing energy—can be constrained with 21-cm data. The 21-cm constraints complement those obtained from particle accelerators, which are more suited for probing stronger dark-matter interactions.

To confirm the EDGES results, several additional experiments are underway, including the SARAS-2, LEDA, and PRIzM collaborations. The locations of these antennas in different hemispheres, as well as their different experimental designs, are essential for eliminating the possibility of instrumental or environmental contributions to the EDGES signal. Low-frequency interferometers, such as the previously mentioned LOFAR and HERA, will map the 21-cm fluctuations on the sky and verify the validity of the reported sky-averaged signal using an array of antennas instead of a single detector.

Studies of the cosmic dawn have a bright future ahead. When one of us published a textbook on this field five years ago, when data were scarce [12], he hoped that new physics unraveled by discoveries at 21 cm would require the book be revised. The reported EDGES signal brings us closer to fulfilling this hope.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

References

- J. D. Bowman, A. E. E. Rogers, R. A. Monsalve, T. J. Mozdzen, and N. Mahesh, “An Absorption Profile Centred At 78 Megahertz in the Sky-Averaged Spectrum,” Nature 555, 67 (2018).

- J. B. Muñoz and A. Loeb, “A Small Amount of Mini-Charged Dark Matter Could Cool the Baryons in the Early Universe,” Nature 557, 684 (2018).

- A. Berlin, D. Hooper, G. Krnjaic, and S.D. McDermott, “Severely Constraining Dark- Matter Interpretations of the 21-cm Anomaly,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 011102 (2018).

- A. Fialkov, R. Barkana, and A. Cohen, “Constraining Baryon–Dark-Matter Scattering with the Cosmic Dawn 21-cm Signal,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 011101 (2018).

- D. D’Amico, P. Panci, and A. Strumia, “Bounds on Dark-Matter Annihilation from 21-cm Data,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 121, 011103 (2018).

- J. C. Kapteyn, “First Attempt at a Theory of the Arrangement and Motion of the Sidereal System,” Astrophys. J. 55, 302 (1922).

- C. M. Hirata, “Wouthuysen-Field Coupling Strength and Application to High-Redshift 21-cm Radiation,” Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 367, 259 (2006).

- Hiroyuki Tashiro, Kenji Kadota, and Joseph Silk, “Effects of dark matter-baryon scattering on redshifted 21 cm signals,” Physical Review D 90, 083522 (2014); Tracy R. Slatyer, “Indirect dark matter signatures in the cosmic dark ages. I. Generalizing the bound ons-wave dark matter annihilation from Planck results,” 93, 023527 (2016).

- Rennan Barkana, “Possible interaction between baryons and dark-matter particles revealed by the first stars,” Nature 555, No. 7694, 71-74 (2018).

- Julian B. Muñoz, Ely D. Kovetz, and Yacine Ali-Haïmoud, “Heating of baryons due to scattering with dark matter during the dark ages,” Physical Review D 92, 083528 (2015).

- J. B. Muñoz, C. Dvorkin, and A. Loeb, “21-cm Fluctuations from Charged Dark Matter,” arXiv:1804.01092.

- A. Loeb and S.R. Furlanetto, The First Galaxies in the Universe (Princeton University Press, Princeton, NJ, 2013)[Amazon][WorldCat].