The turbulent matter field of ultracold atoms

Nowadays, the term turbulence is being used in a much broader context than its original classical hydrodynamic meaning of cascading vorticity. Classically, turbulence arises as fluid motion spawns swirls that break into smaller and smaller swirls, leading to vortices at all length scales. In superfluids, however, quantization of velocity circulation in the superfluid component coupled to a continuous vorticity distribution of the normal component leads to significant differences between classical turbulence at large Reynolds number (the ratio of inertial to viscous forces, and usually a measure of when turbulence occurs) and superfluid turbulence. On the other hand, under appropriate conditions, superfluid turbulence resembles that seen in the classical ideal fluid. Yet another regime, so-called weak turbulence, has nothing to do with vorticity and is used in the context of the almost independent motion of weakly interacting dispersive waves (or Fourier harmonics) in some classical field. Remarkably, all these qualitatively different turbulent regimes can be realized in a system of ultracold bosons, and a paper in Physical Review Letters by Emanuel Lima Henn, Jorge Amin Seman, Kilvia Mayre Farias Magalhães, and Vanderlei Bagnato at the University of Sao Paulo, Brazil, and Giacomo Roati at the University of Florence, Italy [1], reports an elegant and efficient technique of producing them.

One smoking gun of quantum collective behavior in a weakly interacting gas of bosons is when the system can be described by the Gross-Pitaevskii equation—also known as the nonlinear Schrödinger equation in the broader context of nonlinear physics—which is written in terms of a classical complex-valued matter field . There is a perception that such a description inevitably implies that the system possesses a Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC)—with the matter field being nothing but the condensate wave function—and thus is long-range-ordered. In fact, the only necessary requirement for a weakly interacting Bose gas to be described by the Gross-Pitaevskii equation in terms of the complex classical matter field is that the occupation numbers of relevant single-particle modes be much larger than unity (see Ref. [2] for more detail). For weakly interacting bosonic atoms, the field plays a role that is qualitatively equivalent to that played by a classical electromagnetic field with respect to photons. Correspondingly, the Gross-Pitaevskii equation is equivalent to the Maxwell equations for a classical electromagnetic field, known to be accurate as long as the occupation numbers of photons are much larger than unity. A disordered (turbulent) classical-field subsystem of a weakly interacting gas of bosons is responsible for equilibrium criticality of the system, as well as for strongly nonequilibrium kinetics of Bose-Einstein condensation [3].

Until very recently, turbulence in the classical matter field eluded direct experimental study. A physical reason is that, in an equilibrium gas, the part that is not condensed can only involve a small fraction of the total amount of quantum matter. Hence, working with or starting from an equilibrium system, one is bound either to study small corrections to density distributions or to isolate classical-field modes by instantly depopulating the quantum modes. The latter technique was recently utilized by Weiler et al. [4] to obtain the first (and still circumstantial) experimental evidence of the presence of a turbulent classical matter field in the initial state. Weiler et al. observed a vortex formed during the nonequilibrium kinetics of Bose-Einstein condensation, for which a detailed scenario in a weakly interacting gas had been established theoretically [3,5].

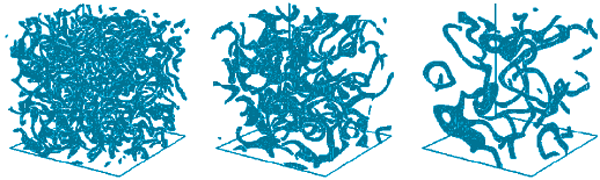

Rather than working with a naturally disordered but small classical-field component of an equilibrium system, Henn et al. start with a pure Bose-Einstein condensate and rely on its intrinsic Gross-Pitaevskii dynamics in the presence of an external oscillatory perturbation (in this case an oscillating magnetic field). The system then evolves towards a turbulent state featuring many chaotic vortices, akin to the state that forms at a certain stage of a strongly nonequilibrium process of Bose-Einstein condensation in a macroscopically large system (Fig. 1). The authors report that their turbulent state demonstrates a distinctively different—from both pure BEC and normal gas—pattern of free expansion.

The dynamics of the matter field produced by Henn et al. is quite different from the dynamics of vortices in classical turbulence or in superfluid helium turbulence. The characteristic distance between vortices is comparable to their core sizes, meaning that the vortices are not well structured and thus do not obey the Biot-Savart law that governs the motion of thin vortex lines in an ideal fluid. Furthermore, with even stronger external perturbation, one may expect that the vortices will be completely destructured and that the classical field will enter the regime of weak turbulence (left panel in Fig. 1)—seen in other nonlinear systems such as plasmas, fluids, and nonlinear optics—when the interaction between harmonics becomes perturbative and is accurately described by a kinetic equation within the random-phase approximation.

Attaining the transition from strong turbulence to weak turbulence with the technique by Henn et al. and then letting the system evolve on its own towards restoration of long-range order appear to be major attractions along the exciting road of exploring nontrivial regimes of classical matter fields in atomic systems. The main fundamental question posed by the experiment is what is the exact mechanism by which long-range order can be destroyed by the oscillating external perturbation, including the crossover from a strongly to weakly turbulent matter field? Future experiments and theoretical effort should provide many interesting insights into the classical-field behavior of ultracold atoms.

References

- E. A. L. Henn, J. A. Seman, G. Roati, K. M. F. Magalhães, and V. S. Bagnato, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 045301 (2009)

- Yu. Kagan and B. V. Svistunov, Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 3331 (1997)

- B. V. Svistunov, J. Moscow Phys. Soc. 1, 373 (1991); Yu. Kagan, B. V. Svistunov, and G. V. Shlyapnikov, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 101, 528 (1992)[Sov. Phys. JETP 75, 387 (1992)]; Yu. Kagan and B. V. Svistunov, Zh. Eksp. Theor. Fiz. 105, 353 (1994) [ibid. 78, 187 (1994)]

- C. N. Weiler et al., Nature 455, 948 (2008)

- N. G. Berloff and B. V. Svistunov, Phys. Rev. A 66, 013603 (2002)