Pressing some boundaries in Mendeleev’s chart

Hydrogen sits prominently at the top left corner of Mendeleev’s imposing periodic table of the elements. It is our most abundant element by far (more than by number) and across the sciences hydrogen’s presence is ubiquitous. This is potently revealed in hydrogen’s role in the chemical combinations that form molecules, liquids, and solids and its proclivities for other elements, which result in stoichiometries largely guided by familiar bonding rules. The rules generally assume the elements have their standard valences (while acknowledging possible deeper complexity arising from the “nonvalence” electrons); but for “normal” conditions we should be able to anticipate how most simple molecules will form.

In a paper appearing in Physical Review Letters [1], Timothy Strobel, Maddury Somayazulu, and Russell Hemley at the Carnegie Institute in Washington, DC, in the US, present a phase diagram of a hydrogen-based compound under pressure that calls into question some of the rules of thumb guiding the bonding of hydrogen. They study the well-known industrial compound, silicon tetrahydride (silane, or ), mixed with and discover a new, well-ordered solid compound, , forming at pressures above . The bonding of hydrogen in this compound is substantially weaker than other known hydrogen based compounds. And, given that consists of silicon, which typically will be associated with four covalent bonds, and hydrogen, which prefers one, we are certainly challenged to understand how can be taking up so much hydrogen. Indeed, it is some hydrogen. Moreover, the measurements of Strobel et al. suggest that we may now have at hand a system based on the simplest element in the periodic table, in which we can study not only a pressure induced metal-insulator transition, but also quantum diffusion and, potentially, superconductivity.

It should be emphasized that the group is not studying under what we might term “normal” conditions, since they are applying pressures of up to . By doing so, they compress the mixture into a new solid and a new chemical form which, as mentioned, does not have a bond arrangement that would usually be observed at atmospheric pressure. The covalent bond is typically viewed as robust and a source of the rich physics of its condensed state [2], but in some of its bonds are significantly weaker than in other molecular compounds. The explanation for the large hydrogen content in appears to be associated with the fact that the standard bonding states of hydrogen are actually vulnerable to significant modification when, under fairly dense conditions, an intruder such as silicon encroaches upon them, even in quite small amounts.

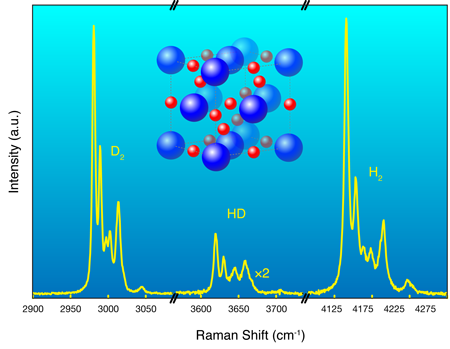

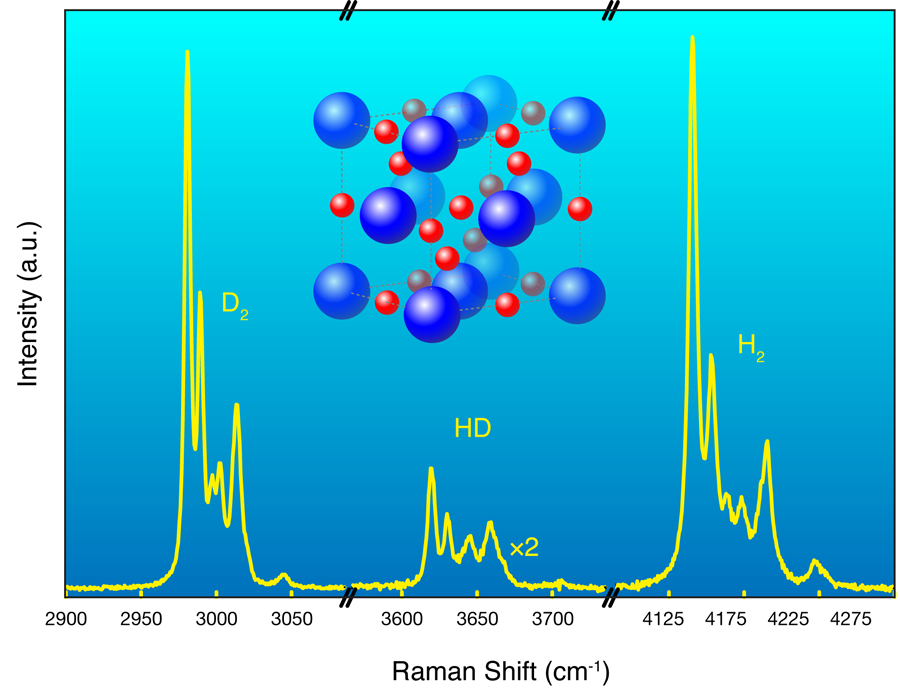

With x-ray diffraction, the group shows that the newly discovered has a high-symmetry, face-centered-cubic (fcc) based structure (inset, Fig. 1). For ordered basis atoms, and assuming an independent electron picture, we know that twelve valence electrons (four from , eight from ) per crystallographic unit cell can then, in principle, fill six bands. This means could also be an insulator, which in fact, it appears to be, at least at lower pressures. However, it is possible that the systematic increase in density under pressure would cause the bands to overlap and if so it is worth understanding more fully the nature of the “bonds” just prior to this overlap of bands.

We already know that pure, solid, hydrogen turns black under pressure—indicating that it is on its way to becoming a metal—but this only occurs under about tenfold compression, which requires in excess of in pressure [3]. It takes only about one tenth of this pressure to darken [4–6]. Similarly, Strobel et al. are finding that also blackens in a comparable pressure range; but given that is embedded in a hydrogen environment at the level of just over 10 atomic percent, this finding indicates an average electron rearrangement that is both extensive and possibly quite subtle.

Hydrogen possesses no core (or nonvalence) electrons and so it, and many hydrogen-based compounds, occupy a somewhat special position in our efforts to understand electronic structure. The nuclei (protons for ) usually take up time-average positions, which are almost invariably assumed fixed, and these critically reflect the time average charge densities taken up by the electrons. Optical experiments, such as the Raman effect, can probe the momentary departures from the average positions, and it then reveals information on the collective dynamics of the protons and hence the underlying structure. This is one technique Strobel et al. use to follow the structural progression in the system as they change the pressure.

Hydrogen, as an isolated molecule , is also a highly quantum system. The protons have zero-point energies equivalent to over per proton and, as Strobel et al. have observed, the standard assumption of fixed average positions, so common in electronic structure calculations, actually seems to fail. The system they study is ideally suited to systematic deuteration [6], in this case through the addition of (i.e., ) to (rather than of , i.e., ). This allows them to check any role that nuclear mass might have on subsequent electron arrangement. Deuteration doubles the mass of hydrogen (and changes the fundamental quantum statistics) but does not change any of the basic underlying interactions. So, what do the data show? As the Raman spectrum in Fig. 1 reveals, instead of the and nuclei remaining quiescently at their “expected” and initial average sites, they literally exchange positions (see caption, Fig. 1). Similar behavior has recently been observed in another dense quantum solid, in fact one that again contains hydrogen [7].

These notably quantum characteristics may play an interesting role in the structural phase transition that occur when, by thermal means, high hydrides might be agitated sufficiently to take up liquid forms. In terms of hydrogen concentration the data so far are scant, but broadly consider how the hydrogen content may affect the melting point of various silicon compounds at one atmosphere: (i.e., pure silicon) melts at , at , and (i.e., pure hydrogen) at . Semiconducting forms a higher density metallic state on melting and, as might be expected from the Clausius-Clapeyron law, its melting point declines with pressure, in fact by close to near . The present experiments, primarily with , or , are already reaching , and the suggestion is that it may be illuminating to pursue structural studies to somewhat higher temperatures (and to even higher hydrogen concentration, for example, in ) in search of a corresponding fluid. For example, it could be especially revealing to find a sign of an extensive liquid metallic domain in a hydrogen-rich system. Further, if at constant pressure, a rapid decline in melting point as a function of increasing hydrogen concentration was to be observed, but to extremely low temperatures, it would indicate a progressive link beyond an initially eutectic form to the near ground-state quantum liquid metallic phase of hydrogen, which has already been mooted.

In addition to becoming metallic at moderate densities, has also been observed to then undergo a transition to a superconducting state [5] (interestingly the standard valence electron count of is identical to that of [6]). If the reported darkening of happens also to presage the onset of a metallic state, we might surely ask if metallic could also be a superconductor? If so, then deuteration experiments could again be helpful in determining whether the underlying mechanism for superconductivity is attributable to the familiar coupling of electrons to lattice dynamics. For this mechanism the superconducting transition temperature is generally expected to drop for a heavier isotope, but this is not what happens, for example, in the hydrogen bearing system. Rather, in alloys of palladium-hydrogen ( ), palladium-deuterium ( ), and even palladium-tritium ( ), the hydrogenic isotope effect is dramatically inverse [8]. This type of behavior has also been predicted to occur for superconductivity in pure metallic hydrogen [9].

At the length scales of interest to the condensed matter sciences, extended systems can be viewed as assemblies of positively charged nuclei embedded in neutralizing equivalents of much lighter but highly quantum and Fermionic electrons. At this level, all interactions are strictly Coulombic and, as Dirac showed 80 years ago [10], the fundamental quantum mechanical problem can be established exactly. All of the electrons are involved and the role of high-pressure physics has been to force those nominally “valence” electrons into the regions between the nuclei (and away from the cores with their locally spherical symmetry). Eventually, relentless increase of pressure can literally strip away the traditionally “nonvalence” electrons from the nuclei, as we know happens in stellar, and some planetary, interiors.

Solving the all-electron problem within the Born-Oppenheimer approximation (least well satisfied, as it turns out, for hydrogen) has involved an enormous level of effort since Dirac’s time, both in experimental and theoretical terms, and in the domains of chemistry, condensed matter physics, and elsewhere. The later notable advances in electronic density functional techniques and other electronic structure calculational methods actually allow us to ask whether stoichiometries and combinations of light element binaries other than those associated with common valences could in fact be predicted? This seems to be the case now, even for combinations of hydrogen with another Group I element [11], but it is clearly an area open for wider exploration.

Though perhaps fanciful when considered at the 140 year mark, we might wonder about Mendeleev’s further progress had he benefited from some very extensive additional data [12]. The properties and regularity of the elements in various compounds led, in part, to his ability to systematize them. But, of course, these regularities were observed at atmospheric pressures. Suppose Mendeleev had also been in command of similar data from combinations corresponding to, say, four- to fivefold condensed phase compressions? The appearance of different sequences of regularities in higher density compounds may have indicated electron distributions significantly altered from those at one atmosphere. More generally the concept of a precise valence, already known to fluctuate in some binary systems, might then begin to appear to be a low-density construct. With the ability of pressure to reduce average internuclear separations considerably, it leaves us with the question: In the end, will there be any rigorous difference between valence and core electrons as pressure inexorably drives systems towards plasma states, hydrogen being a prominent case [13]?

The paper from Strobel et al. demonstrates the critical ongoing importance of experiment in addressing these questions, even while acknowledging great strides made in electronic structure calculations. And the pressure variable is also seen to continue to hold very considerable promise in illuminating the electronic and structural physics of systems with ever increasing densities.

Acknowledgments

Support of the National Science Foundation under Grant DMR 09-0907425 is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- T. A. Strobel, M. Somayazulu, and R. J. Hemley, Phys. Rev. Lett. 103, 065701 (2009)

- I. F. Silvera, Rev. Mod. Phys. 52, 393 (1980)

- P. Loubeyre, F. Occelli, and R. LeToullec, Nature 416, 613 (2002)

- X-J. Chen, V. V. Struzkin, Y. Song, A. F. Goncharov, M. Ahart, Z. Liu, H-K. Mao, R. Hemley, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 20 (2008)

- M. I. Eremets, I. A.Trojan, S. A. Medvedev, J. S. Tse, Y. Yao, Science 319, 1506 (2008)

- N. W. Ashcroft, Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 187002 (2004)

- V. V. Khmelenko, E. P. Bernard, S. Vasilev, D. M. Lee, Russian Chemical Reviews 76, 1107 (2007)

- J. E. Schirber, J. M. Mintz, and W. Wall, Solid State Commun. 52, 837 (1984)

- K. Moulopoulos and N. W. Ashcroft, Phys. Rev. B 59, 12309 (1999)

- P. A. M. Dirac, Proc. R. Soc. A 123, 714 (1929)

- E. Zurek et al. (submitted for publication)

- D. A. Young, Phase Diagrams of the Elements (University of California Press, Berkeley,1991), especially the last chapter[Amazon][WorldCat]

- E. Fortov et al., Physics of Strongly Coupled Plasma, International Series of Monographs on Physics Vol. 135 (Oxford Science Publications, Oxford, 2006)[Amazon][WorldCat]