Testing gravity in gas-rich galaxies

The rotation curve of a galaxy is the orbital speed of material as a function of distance from the center of the galaxy. In the 1970s, the astronomer Vera Rubin measured the rotation curves of several of the nearest spiral galaxies. To her astonishment, the curves remained flat beyond the edge of the galaxy’s stellar disc [1]. Under the standard theory of gravity this implies that the mass in the outskirts of these systems far outweighs that of the detected gas and stars. Today, the flatness of spiral galaxy rotation curves remains key evidence for dark matter, which, broadly defined, is matter that obeys the law of gravity but does not emit any light.

Dark matter is an integral component of the currently favored cosmological model, in which over 90% of the matter in the Universe is made up of massive (“cold”) particles, which interact only via gravity. The model is named Lambda-Cold Dark Matter ( ΛCDM), with Λ denoting a cosmological constant (sometimes called “dark energy”) that accelerates expansion at late cosmological times. An impressive array of observations fit this picture, from the spectrum of fluctuations in the cosmic microwave background (the first free-streaming photons in the Universe, e.g., Ref. [2]), to the luminosities of distant supernovae [3,4]. The astrophysical community has adopted ΛCDM as the standard cosmological model, which makes the nature of dark matter one of the most important outstanding questions in the field.

But not all cosmologists are happy with this picture. Some are uneasy with the unknown components in the standard model, and worry that cosmology in the last 30 years has degraded into “naming the unknown” (e.g., Ref. [5], but see also Ref. [6]). In spiral galaxies at least, an alternative to invoking dark matter is to modify the theory of gravity in regions where there is a discrepancy between the mass inferred from dynamics (using standard gravity) and the baryonic mass (i.e., the census of normal material detected in stars and gas). The most successful of these ideas is MOND (Modified Newtonian Dynamics [7]), which modifies gravity at small accelerations to produce flat galactic rotation curves. For gravitational accelerations a less than some critical value a0, the usual Newtonian relation F=ma is modified to F=ma2/a0, and therefore the circular velocity around a mass M asymptotes to a constant value vf=(GMa0)1/4. Once the universal constant a0 is fixed observationally, MOND explains the rotation curve shapes of galaxies using their baryonic mass alone, while simultaneously accounting for the observed correlation between their rotation velocities and luminosities.

By construction, MOND requires that the baryonic mass of a galaxy is proportional to the 4th power of its circular velocity: Mb∝v4f. An independent verification of this relationship is impractical in typical spiral galaxies in which stars dominate the baryonic mass, because it is difficult to reliably infer the total stellar mass M*. Although most of the light in a galaxy comes from massive stars, most of the stellar mass in the galaxy is hidden inside faint low-mass stars. To estimate the stellar mass of a galaxy from how much light it emits, one needs a model that combines well-understood stellar physics with estimates of the mass and age distributions of the stars in the galaxy. Such models exist (e.g., Ref. [8]) but suffer from significant systematic uncertainties that may correlate with mass. To avoid these uncertainties, one is forced to invoke MOND to measure M* from galaxy rotation curves, which imposes the Mb∝v4f relation on the data. In this scenario this relation is not a prediction of MOND, but rather a consequence of imposing MOND to obtain Mb at the outset.

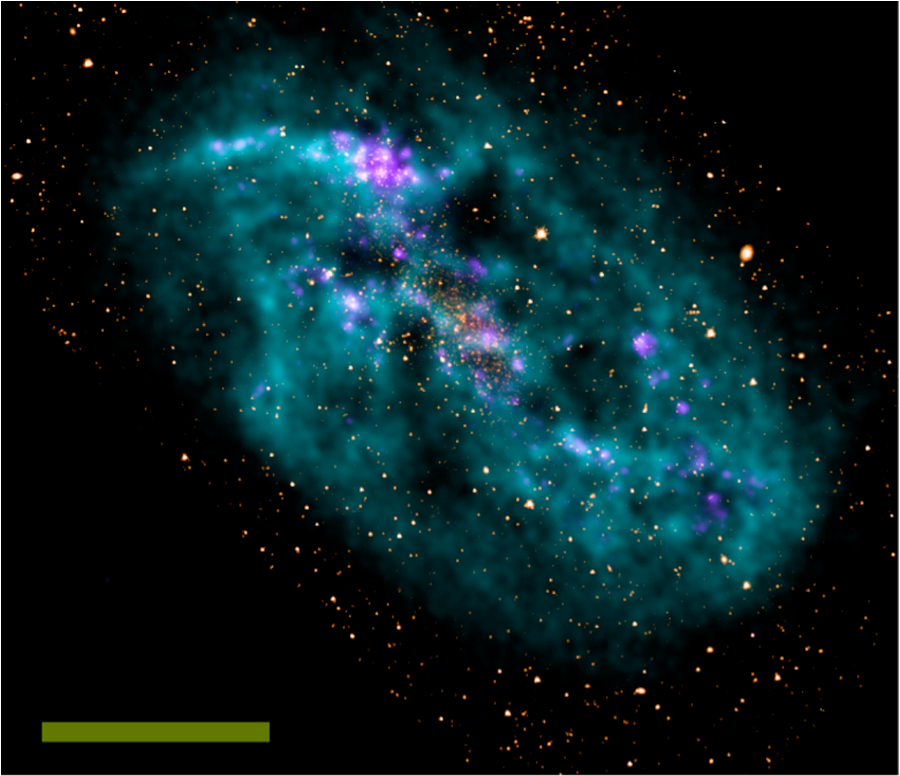

In a paper in Physical Review Letters [9], Stacy McGaugh at the University of Maryland, US, suggests that for a class of galaxies with stellar masses that are outweighed by their atomic gas masses (e.g., Fig. 1), the Mb∝v4f relation can be used to test the validity of MOND. Unlike stellar masses, atomic gas masses are straightforward to measure using the “ 21cm line”—an emission line at a rest wavelength of 21cm (observable with radio telescopes), which is produced by the hyperfine spin-flip transition of ground-state atomic hydrogen. Because atomic hydrogen gas is the primary contributor to Mb in these galaxies, systematic uncertainties in stellar masses become unimportant. Mb and vf can therefore be measured independently from any cosmological or gravity theory and used to test MOND.

McGaugh collects from the literature a sample of 47 gas-rich galaxies, for which recent 21cm spectral line observations provide reliable estimates of both their atomic gas masses (which are combined with stellar population model masses to produce Mb) and their asymptotically flat rotation velocities vf. These data show an impressive match with the MOND prediction of Mb∝v4f, and also agree well with the acceleration parameter a0 required to fit the rotation curves of star-dominated galaxies. McGaugh further claims that the data have no scatter about the MOND prediction beyond measurement errors. This statement appears to be premature since statistical incompleteness, large distance uncertainties (many of the galaxy masses rely on estimated distances only), and other observational realities do not seem to have been taken into account. These will introduce biases into the observed scaling and have been shown to reduce the observed scatter (e.g., Ref. [13]). Such biases will most likely not significantly change the observed correlation, but they cast doubt on the exact details, particularly the interpretation of the scatter.

The Mb∝v4f relationship can be interpreted in ΛCDM, only by requiring a particular scaling between the baryonic and dark-matter mass of a galaxy (specifically that the detectable fraction of baryons is proportional to the rotation velocity). There are well-known astrophysical processes—such as energetic feedback from star formation—that produce the right qualitative trend, but some tuning is required to match the details. That MOND so readily explains the observed relationship is a new triumph for the model in the context of these gas-rich galaxies.

McGaugh’s result adds a new facet to the argument that MOND is better at explaining galaxies than standard cosmology. However, as McGaugh admits, MOND cannot compete with ΛCDM as a full cosmological theory. Attempts to generalize MOND into a fully relativistic theory of gravity abound, but even the most promising ones (e.g., tensor-vector-scalar, or TeVeS [14]) struggle to interpret the combination of large-scale observations of the Universe that ΛCDM explains so well. The tuning required in MOND, most notably to explain the dynamics of galaxy clusters, is more severe than that faced by ΛCDM to match galaxy rotation curves. We know that standard but poorly understood baryonic physics plays an important role in shaping the properties of galaxies in ΛCDM. Reconciling MOND with galaxy clusters, on the other hand, requires invoking significant amounts of the missing matter, which MOND was conceived to avoid in the first place.

The test proposed by McGaugh is a critical one for MOND, and his application of it to recently observed gas-rich galaxies is an important proof of concept. An ideal sample for this test should soon be within reach as surveys with the next generation of radio telescopes produce large catalogs of spatially resolved gas-rich galaxies. Whether or not MOND fares as well with future samples as McGaugh finds in this work, it is clear that no viable cosmological scenario is complete unless it can explain the remarkable success of the MOND phenomenology in spiral galaxies.

References

- V. C. Rubin, W. K. J. Ford, and N. Thonnard, Astrophys. J. 238, 471 (1980)

- E. Komatsu et al., Astrophys. J. Supp. 180, 330 (2009)

- A. G. Riess et al., Astron. J. 116, 1009 (1998)

- S. Perlmutter et al., Astrophys. J. 517, 565 (1999)

- U. Sawangwit and T. Shanks, Astron. Geophys. 51, 5.14 (2010)

- T. Giannantonio, A. Lewis, and R. Crittenden, Astron. Geophys. 51, 5.16 (2010)

- M. Milgrom, Astrophys. J. 270, 365 (1983)

- C. Maraston, Mon. Not. R. Astron. Soc. 300, 872 (1998)

- S. S. McGaugh, Phys. Rev. Lett. 106, 121303 (2011)

- F. Walter, E. Brinks, W. J. G. de Blok, F. Bigiel, R. C. Kennicutt, M. D. Thornley, and A. Leroy, Astron. J. 136, 2563 (2008)

- R. C. Kennicutt et al., Publ. Astron. Soc. Pac. 115, 928 (2003)

- A. Gil de Paz et al., Astrophys. J. Suppl. 173, 185 (2007)

- K. L. Masters, C. M. Springob, M. P. Haynes, and R. Giovanelli, Astrophys. J. 653, 861 (2006)

- J. D. Bekenstein, Phys. Rev. 70, 083509 ( (2004)