The Twins of Turbulence Research

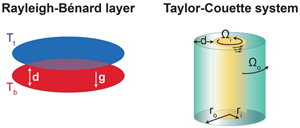

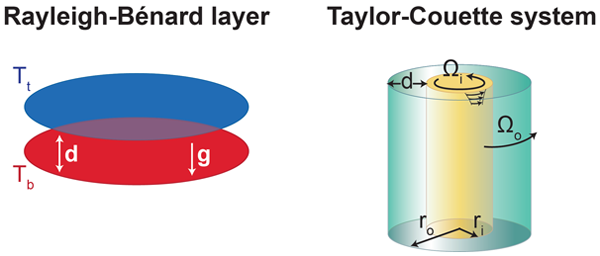

Thermal convection in a fluid layer heated from below (Rayleigh-Bénard layer) and flows between coaxial differentially rotating cylinders (Taylor-Couette system) have been investigated for more than a century, experimentally as well as theoretically. Both are attractive systems for laboratory investigations of fluid turbulence because visualizations and data gathering are easier than in experiments on pipe and channel flows. According to two recent papers [1,2] in Physical Review Letters, sufficiently high intensities of turbulence have now been achieved in the two cases such that the “asymptotic” regime has been attained where simple relationships between turbulent transports and external parameters hold. The Rayleigh- Bénard case was investigated by Xiaozhou He and colleagues at the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self Organization, Germany, and the Taylor-Couette system by Sander Huisman and colleagues at the University of Twente, Netherlands.

The asymptotic relationships are not only important for engineering applications but are also needed for the understanding of turbulent transports in natural systems, such as the Earth’s atmosphere and oceans and the atmospheres of planets and stars. Based on the experimental results, it will be possible to obtain more reliable expressions for those transports.

Although the two experimental configurations shown in Fig. 1 look rather different, they have much in common. As Rayleigh [3] already noticed, the basic stability criteria for inviscid fluids are essentially the same. The angular velocity distribution Ω(r) as a function of the distance r from the axis of the cylinders is stable with respect to axisymmetric disturbances as long as

holds. The analogous criterion for the Rayleigh-Bénard layer states the rather trivial result that the static configuration is stable as long as

holds, where z is the vertical coordinate opposite to the direction of gravity g, and the density ρ is a function of z. In the realistic case of viscous fluids, the stability criteria (1) and (2) must be replaced by Ta<Tac and by Ra<Rac, where the Rayleigh number Ra and the Taylor number Ta are defined by

Here, ν is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid, κ is its thermal diffusivity, α is the coefficient of thermal expansion, and η is the radius ratio of the cylinders, η=ri/ro. d denotes the height of the convection layer and also the gap width between the cylinders, d=ro-ri. The Rayleigh number can thus be interpreted as the ratio of buoyancy to viscous and thermal dissipation effects, and the Taylor number represents the square of the ratio of inertial force versus viscous friction. In the limit

the relationship ˆΩ(√Tac-ˆΩ)=Rac holds, which demonstrates the close connection of the two stability conditions as first noted by Low [4]. Here the definition ˆΩ≡(Ωi+Ωo)d2/2ν for the dimensionless mean rotation rate has been used.

The exact mathematical equivalence of the stability criteria continues to hold with ˆΩ(√Ta-ˆΩ)=Ra for the fully nonlinear equations of the two problems if the attention is restricted to two-dimensional solutions and if the Prandtl number (which compares viscous diffusion with thermal diffusion) is set equal to unity, Pr≡ν/κ=1. In the three-dimensional case, the two systems differ substantially since the Rayleigh-Bénard convection problem is isotropic in the horizontal plane, while the Taylor-Couette problem is strongly anisotropic. This difference becomes less important as turbulence develops since the large-scale circulation in the convection box indicates a preferred horizontal direction, just as the azimuthal shear does in the Taylor-Couette system.

Both turbulent convection and turbulent Taylor-Couette flow represent transport processes characterized by turbulent interiors and boundary layers close to the solid walls. These boundary layers can still be nearly laminar since the fluctuating velocity field vanishes at the boundaries. In the case of Rayleigh-Bénard convection, one must distinguish between thermal and kinetic boundary layers when the Prandtl number differs significantly from unity. But since in the experiment [1] the values of ν and κ do not differ much, there is no need here to worry about this distinction. In the asymptotic or ultimate regime of high Reynolds numbers, the boundary layers will be just as turbulent as the interior. This regime has been the focus of both papers [1,2].

Grossmann and Lohse [5] have recently studied, from a theoretical point of view, the asymptotic regime when the turbulence of the bulk engulfs the boundary layers and new balances affect the transport processes and the level of turbulence. They have derived relationships of the form:

Rayleigh-Bénard system

Taylor-Couette system

for the Nusselt numbers Nu and Nuω and for the Reynolds numbers Rew ( Reeff in [1] ) based on a characteristic turbulent velocity vw, Rew=vwd/ν. The Nusselt numbers are defined as the ratio between the total transport of heat or angular momentum and the transport that would occur solely through the action of viscosity or thermal conductivity. The important property of the above results is that the relationships (7) and (9) for the Reynolds numbers Rew hold without the logarithmic corrections that are significant for the transport efficiencies (6) and (8). This result is in contrast to similar relationships derived by Kraichnan [6] who found logarithmic correction factors also for the dependences of the Reynolds numbers.

The main achievement of the experimental investigations [1,2] is that their measurements confirm the scaling relationships (6)–(9) and provide numerical values for the proportionality factors. To reach this goal the experimenters had to overcome many obstacles. To increase Rew in the Rayleigh-Bénard case, the gas sulphur hexafluoride ( SF6) was used at high pressures up to 19 bars in order to minimize ν and κ. The height d was increased to 2.24m, which was possible only through the use of a low aspect ratio, i.e., the “horizontal layer” was confined to a vertical cylinder with a diameter equal to half its height. Similarly, the dimensions of the Taylor-Couette apparatus were enlarged considerably beyond those of earlier experiments.

The transition to the ultimate state, characterized by the relationships (6)–(9), occurs discontinuously over a range of Rayleigh numbers from Ra*1=1013 to Ra*2=5×1014 in the case of turbulent Rayleigh-Bénard convection. It is remarkable that in this range multistability occurs, i.e., several different states of turbulent convection may be realized depending on initial conditions. This may explain in part the discrepancies between different experimental measurements that have given rise to controversies in the past. In the case of the Taylor-Couette system, the transition to the ultimate state has not yet been explored in detail.

In all areas of science where turbulent transports play a role, such as astrophysics, atmospheric science, and others, more reliable expressions for turbulent transports dependent on external parameters are highly desirable. The experimental results of [1,2] represent an important step in this direction.

References

- X. He, D. Funfschilling, H. Nobach, E. Bodenschatz, and G. Ahlers, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 024502 (2012)

- S. G. Huisman, D. P. M. van Gils, S. Grossmann, C. Sun, and D. Lohse, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 024501 (2012)

- Lord Rayleigh, Proc. London Math. Soc. 11, 57 (1880); Proc. R. Soc. London A 93, 148 (1917)

- A. R. Low, Nature 115, 299 (1925)

- S. Grossmann and D. Lohse, Phys. Fluids 23, 045108 (2011)

- R. H. Kraichnan, Phys. Fluids 5, 1374 (1962)