Unexpected Turbulence in a Splash

Liquid droplets falling onto liquid—such as rain hitting puddles or the sea surface—can generate complex, delicately patterned splashes. Now a team has shown that hidden patterns in these impacts explain why the rim of the splash may break up into a chaotic frenzy of droplets. The researchers used computer simulations and high-speed video to observe the details of a splash as it was created by a drop impact. The structure of a splash can have important effects in the ocean and in industrial processes such as spray-coating.

When it rains over the ocean, the raindrops splash and generate tiny droplets that evaporate to leave airborne salt crystals. These crystals may then affect the formation of clouds, and a better understanding of the initial splash events could help researchers learn more about this process. The structures of such splashes could also affect technological operations such as spray-coating and the dispersal of sprayed pesticides.

Sigurdur Thoroddsen of the King Abdullah University of Science and Technology in Saudi Arabia and his colleagues have previously used high-speed video recording to watch the evolution of splashes generated by droplets falling onto a liquid. They found that if the impact is fast enough and the fluid not too viscous, the droplet throws out a thin, ring-shaped “ejecta sheet,” beginning the moment the bottom of the droplet contacts the liquid surface. The sheet may then shed droplets from its top edge.

Now the team reports that at higher impact speeds this sheet can disintegrate almost at once into a spray of little drops. They recorded splashes from droplets in various liquids, striking with a range of speeds, and characterized the different situations with the Reynolds number, a dimensionless quantity that depends on the ratio of drop velocity to fluid viscosity. With additional input from computer simulations, the researchers determined how the orderly splash switches to a disorderly one as Reynolds number increases.

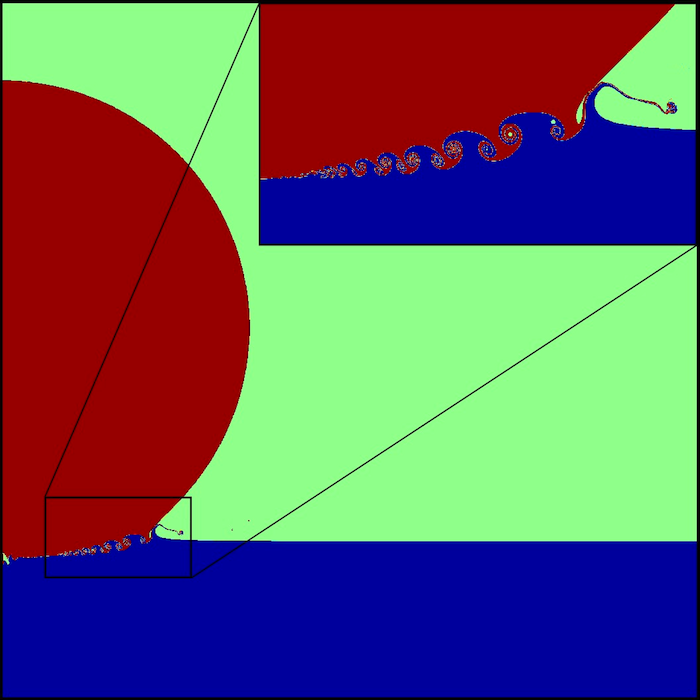

Simulating this flow process was extremely challenging, since it involved a wide range of length scales. The ejecta sheet, for example, becomes extremely thin at its rim: a 6-millimeter droplet can produce a sheet as thin as 300 nanometers. To cope with that, the researchers have developed a simulation technique in which the grid the computer uses to divide up space changes size at each location, depending on the size of the features it must capture. “All previous simulations of this phenomenon have been woefully under-resolved, missing the most interesting aspects of our results,” says Thoroddsen.

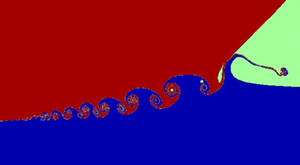

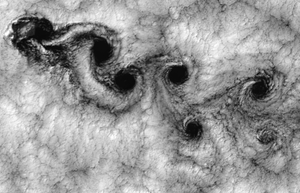

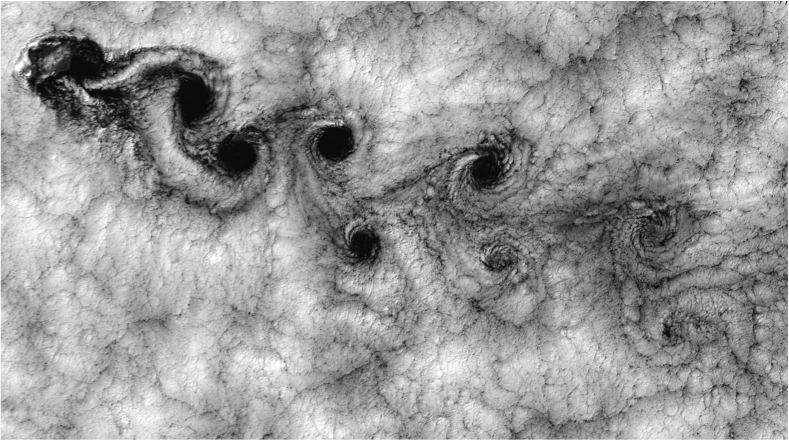

The team found that, if the Reynolds number is large but not too large, a series of concentric, ring-shaped vortices appears at the interface of the two fluids when the drop hits, and the vortices persist as it sinks below the surface. This submerged interface is visible in cross section in the simulations, with a vertical slice through the center of the drop. Viewed edge-on, the ring-shaped vortices are recognizable as a “von Kármán vortex street,” a pattern that often appears when a high Reynolds number fluid flow is disturbed.

In the cross-section view from the simulations, the vortices can be seen forming at the base of the ejecta sheet and moving inward. This “shedding” of vortices begins just after the moment of impact and can make the sheet oscillate up and down, because the vortices rotate in alternating directions. This oscillation promotes the sheet’s breakup into microdroplets. The breakup is further promoted by bubbles trapped in the eddies of the vortex street—these bubbles can form if the sheet hits the side of the falling drop. The simulated breakup into microdroplets matched the team’s video recordings of real splashes.

“What is new is the vortex street, which was neither known nor expected before,” says Michael Brenner, a theorist at Harvard University who has also studied drop splashing. “Despite its ubiquity,” he adds, “the mechanism for splashing in these situations was not even qualitatively understood before.”

The next challenge, says Thoroddsen, is to see the vortex formation experimentally. But since it happens extremely fast—in a few microseconds—he admits that “the imaging will be quite challenging.”

–Philip Ball

Philip Ball is a freelance science writer in London. His latest book is How Life Works (Picador, 2024).

More Information

YouTube videos of simulated von Kármán vortex streets: first video; second video