Make your Spins Spin

Many devices used for computing, information storage, and other electronic applications rely on controlled manipulation of the spin angular momentum carried by electrons. Recent advances in spin-dependent phenomena hold promise for future technologies, but often these effects are hard to detect. In Physical Review Letters, Ronghua Liu and co-workers from Emory University in Atlanta, Georgia, combine two spin effects in a design that takes us closer to further insight and more applications of spin-dependent electronic (spintronic) phenomena [1].

One of the spin effects the authors use is spin transfer torque, which occurs when the spins of an electronic charge current rotate the magnetization orientation of a magnetically ordered material. The other effect used is the spin Hall effect, which occurs when electrons move through a conductor under the influence of an applied electric field. This, in turn, splits the electrons into spin-up and spin-down populations that move towards opposite sides of the sample.

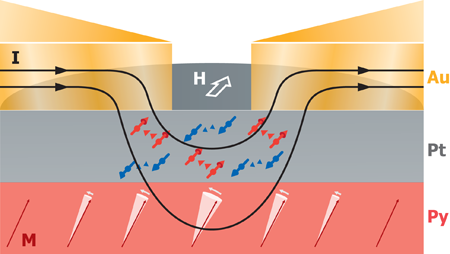

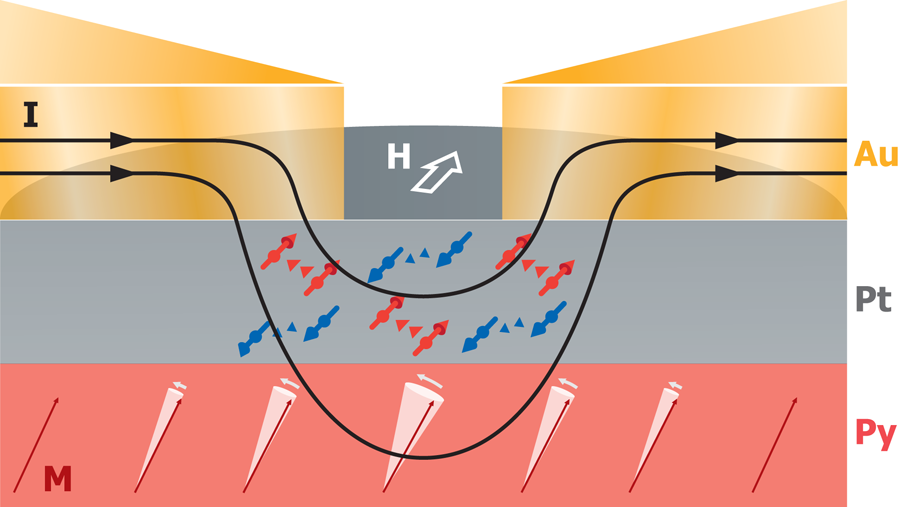

With these effects, Liu et al. were able to detect magnetization dynamics using electrical transport measurements with devices (Fig. 1) that contained just one single ferromagnetic component—Permalloy (a magnetic nickel-iron alloy)—instead of the commonly used two-component systems. One of the main advances of this work is that compared to earlier experiments, this detection does not require sophisticated optical spectroscopy or complex device structures, therefore this experimental approach will be accessible to a wide range of research groups. This result should thus provide both a different approach for spintronic devices as well as a better understanding of magnetic dynamics.

So, how does one achieve these spin effects? One common way of creating spin transfer torque is by passing a charge current through a ferromagnetic conductor, which induces a net spin polarization. When such a spin-polarized charge current subsequently enters another ferromagnetic material, the interactions of the spins with the magnetization may give rise to a change of the direction (switching) of the magnetization or the excitation of sustained precession (dynamics) of the magnetization. In order to generate the high spin-current densities required to induce sufficient spin transfer torque for applications, experiments on these phenomena are generally limited to small-scale contacts or pillars, which may be challenging to fabricate. Nevertheless, even with this limitation, devices based on spin transfer torque effects already have been used in nonvolatile memory and small-scale microwave generation.

The second ingredient in the team’s approach is the spin Hall effect. This is a way of generating spin currents without relying on direct electrical injection of spin-polarized charge currents from additional ferromagnetic conductors. The spin Hall effect is based on the coupling between electron spin and orbital motion that exists even in nonmagnetic materials. Because of this coupling, electrons moving through a conductor are split up by and separated by spin, which results in a spin accumulation—an imbalance of spin populations—at the surfaces of a charge-current-carrying layer. This spin accumulation can also give rise to spin transfer torque effects and has several interesting advantages over direct electrical injection. For spin transfer torques generated via direct electrical injection, each current-carrying electron can only transfer the angular momentum of one spin to the magnetization of the ferromagnet. In contrast, in the case of spin Hall effects, each electron can transfer several times its spin angular momentum to the ferromagnet by repeatedly scattering at the interface between the conductor and the ferromagnet. Therefore the net spin current generated in a device based on spin Hall effects can exceed the electric charge current. Furthermore, since the spin current is generated in a direction transverse to the charge direction, there is no need for the ferromagnetic material to be conducting, and because of this, the spin transfer torque can also occur in insulating ferromagnetic materials.

In their experiments, Liu et al. use thin layers of platinum for the nonmagnetic conductor since platinum is well known to have relatively strong spin Hall effects [2,3]. At the same time, they use Permalloy for the ferromagnetic layer; Permalloy has very low magnetic anisotropy and damping (effects that inhibit both switching and dynamics) and hence is well suited for studying magnetization dynamics. The team passes a current through the platinum and Permalloy layers via the gold contacts, while the whole device is under the influence of a magnetic field. The use of a direct charge current for generating microwave magnetization dynamics has already been demonstrated for devices using spin Hall effects for spin current generation by three different research groups, but in these previous experiments, the detection of the magnetization dynamics relied on very weak inductive voltages [4], optical detection [5], or integration of a magnetic tunnel junction sensor [6], none of which are trivial to realize. By contrast, Liu et al. directly analyze the microwave spectrum generated from the applied dc charge current, which also passes partially through the ferromagnetic layer, where the magnetization dynamics are excited (see Fig. 1). This typically generates microwaves at several gigahertz because the electrical resistance in ferromagnets depends on the relative angle between charge current and magnetization direction, an effect known as anisotropic magnetoresistance. Therefore, for certain magnetic field directions, the magnetization dynamics and concomitant resistance changes can give rise to voltage oscillations at the microwave frequency characteristic for the magnetization dynamics.

Beyond opening up the field to a wide range of researchers, this approach has a high spectral resolution, especially compared to optical spectroscopy [5], which allows for a detailed investigation of the magnetization dynamics. For example, Liu et al. detected changes of the linewidth as a function of dc current or temperature, which were previously obscured in measurements based on optical detection. Furthermore, the temperature-dependent studies revealed surprising changes, with additional modes appearing at higher temperatures, which clearly points to the need for further investigations of the spin-Hall-driven magnetization dynamics in the future.

Undoubtedly, there are many open questions that remain. In particular, the actual charge-current distribution in the sample is very complex, and therefore there is most likely a very inhomogeneous temperature distribution, which may affect magnetization dynamics. The role of these current and temperature distributions in these samples is not yet resolved, and exploring these issues further will certainly reveal further surprises in our understanding of spin transfer torque effects and spin Hall effects.

From an applied point of view, the simple planar geometry may have advantages for device fabrication, avoiding the necessity for small patterned complex multilayered structures. Furthermore, there is still plenty of room for optimizing the generated microwave power through carefully changing the geometry and choice of materials. Although platinum is one of the materials with relatively high spin Hall efficiencies compared to many other materials [2,3], there have been recent reports of other materials with significantly stronger spin Hall effects, such as copper-bismuth alloys [7], -phase tantalum [8], and tungsten [9]. In addition, the planar geometry may enable better synchronization of several spin transfer torque oscillators, which could offer a viable pathway for higher power microwave generation. Similarly, the planar geometry also allows for direct access to the magnetization dynamics, which may open up new opportunities for actuators and sensors [10]. It will be interesting to see, how the work by Liu et al. will inspire others to add their own spin on this kind of physics.

References

- R. H. Liu, W. L. Lim, and S. Urazhdin, “Spectral Characteristics of the Microwave Emission by the Spin Hall Nano-Oscillator,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 147601 (2013)

- O. Mosendz, V. Vlaminck, J. E. Pearson, F. Y. Fradin, G. E. W. Bauer, S. D. Bader, and A. Hoffmann, “Detection and Quantification of Inverse Spin Hall Effect from Spin Pumping in Permalloy/Normal Metal Bilayers,” Phys. Rev. B 82, 214403 (2010)

- M. Morota, Y. Niimi, K. Ohnishi, D. H. Wei, T. Tanaka, H. Kontani, T. Kimura, and Y. Otani, “Indication of Intrinsic Spin Hall effect in 4 and 5 Transition Metals,” Phys. Rev. B 83, 174407 (2011)

- Y. Kajiwara et al., “Transmission of Electrical Signals by Spin-Wave Interconversion in a Magnetic Insulator,” Nature 464, 262 (2010)

- V. E. Demidov, S. Urazhdin, H. Ulrichs, V. Tiberkevich, A. Slavin, D. Baither, G. Schmitz, and S. O. Demokritov, “Magnetic Nano-Oscillator Driven by Pure Spin Current,” Nature Mater. 11, 1028 (2012)

- L. Liu, C.-F. Pai, D. C. Ralph, and R. A. Buhrman, “Magnetic Oscillations Driven by the Spin Hall Effect in 3-Terminal Magnetic Tunnel Junction Devices,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 186602 (2012)

- Y. Niimi, Y. Kawanishi, D. H. Wei, C. Deranlot, H. X. Wang, M. Chshiev, T. Valet, A. Fert, and Y. Otani, “Giant Spin Hall Effect Induced by Skew Scattering from Bismuth Impurities inside Thin Film CuBi Alloys,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 156602 (2012)

- L. Liu, C.-F. Pai, Y. Li, H. W. Tseng, D. C. Ralph, and R. A. Buhrman, “Spin-Torque Switching with the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tantalum,” Science 336, 555 (2012)

- C.-F. Pai, L. Liu, H. W. Tseng, D. C. Ralph, and R. A. Buhrman, “Spin Transfer Torque Devices Utilizing the Giant Spin Hall Effect of Tungsten,” Appl. Phys. Lett. 101, 122404 (2012)

- X. Wang, G. E. W. Bauer, and A. Hoffmann, “Dynamics Of Thin-Film Spin-Flip Transistors With Perpendicular Source-Drain Magnetizations,” Phys. Rev. B 73, 054436 (2006)