Making Invisible Cracks Visible

A new acoustic imaging concept could make it easier for engineers to find dangerous defects in bridges or airplane wings. Researchers demonstrated the technique’s ability to image cracks in an aluminum block. The system is the first that can locate so-called acoustic nonlinearities—places where multiple sound waves don’t add up as one might expect—in a simple and practical manner. Regions of nonlinearity are often sites of cracks or extreme fatigue, so the technique’s developers hope it will provide an important tool for inspectors.

Traditional “linear” acoustic imaging techniques use an array of transducers to send sound pulses into a material and then measure the reflections, for example, to pinpoint potentially hazardous cracks in a highway bridge. But some cracks aren’t visible with linear imaging. Hairline fractures or cracks oriented edge-on to the incoming sound pulse might generate very small reflected waves.

But cracks have another important acoustic property—in response to a single input frequency, they can generate sound waves of other frequencies. Cracks generate these other frequencies in part because broken bonds allow them space to vibrate in ways that the intact material cannot. The extra frequencies can also come from regions near a crack where fatigue has altered the material’s microstructure. Detecting this property, known as nonlinearity, would allow more cracks to be identified, but nonlinear acoustic techniques in the past have had difficulty locating a specific source of nonlinearity. Practical nonlinear imaging could also be useful for identifying pathologies in biological tissue and for distinguishing different types of rock in geological research, says Jack Potter of the University of Bristol in the UK.

Potter, working with Bristol colleagues Paul Wilcox and Anthony Croxford, has now demonstrated a simple, nonlinear acoustic imaging technique that uses the standard linear imaging equipment. Their system combines two established linear methods. In the first, “parallel” method, sound pulses are sent from all transducers at once, but with a slight delay applied to each transducer, to focus the waves at a single focal point in the material. The transducers then detect the reflected waves. In the second, “sequential” method, each transducer fires in sequence, and the array detects a separate response from each one. For this method, the reflected waves are combined later, in the data processing stage, when the delays are added to give the equivalent of parallel inputs.

These two methods give identical results when applied to a purely linear material, but not when there are nonlinear effects. The difference in the amplitudes of the responses from these two methods, the team realized, is a measure of the nonlinearity at the focal point. By repeating the process with different focal points, they could build up an image of the nonlinearity in the material.

To test their technique, the team created fatigue cracks in an aluminum block by subjecting it to thousands of compression/release cycles, according to a standard protocol. To image a crack, they used an ultrasound device with 64 transducers to send sound pulses into the block with both the parallel and sequential methods. Rather than detecting the immediately-reflected waves, the researchers waited a millisecond before recording the sound level. By that time, the sound had bounced around enough that the intensity was equal everywhere inside the block but still a direct measure of the material’s response at the focal point. They generated an image of the nonlinearity by subtracting the two signals at every point, and the crack showed up cleanly in the image. But it was barely visible with linear imaging.

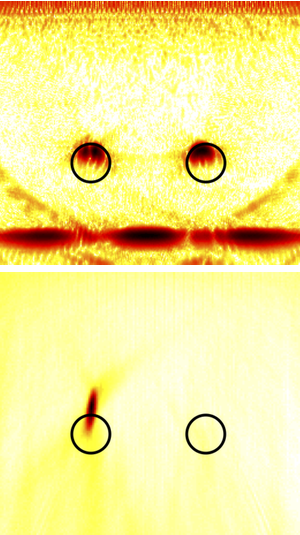

As an additional test, the team drilled a 5-mm-wide hole touching a 2.5-mm-long crack, to mimic the damage at a bolt hole in a load-bearing part. They also drilled a second hole away from the crack, for comparison. The linear method revealed the two holes, but the crack was invisible because it was small and overwhelmed by the strong signal from the nearby hole. The nonlinear method showed the location of the crack clearly, with hardly any sign of the holes.

“For a crack detecting technique to be used, it has to be a practical process,” says Tony Dunhill of Rolls-Royce and the University of Nottingham in the UK. “Techniques that require high levels of precision can fail in practice,” but this one seems practical and accurate, he says.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Emily Conover

Emily Conover is the science writer for APS News.