Remote Controlled Entanglement

Quantum entanglement is not only one of the most puzzling features of quantum mechanics, but it is also a useful resource that can be consumed to realize tasks that would otherwise be impossible. Famous examples are quantum teleportation and quantum cryptography, which are most useful when entanglement is shared between remote parties. Although nearby entangled states can routinely be created using a host of physical systems, optical photons are the natural choice for entangling spatially separated systems. But in Physical Review Letters, Nicolas Roch, from the University of California at Berkeley, and colleagues reported realizing this feat using microwave radiation to measure, and thereby entangle, superconducting circuits separated by meters of coaxial cable [1].

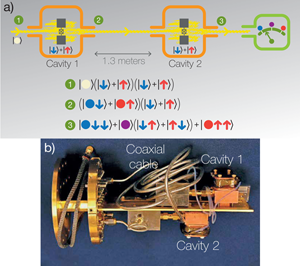

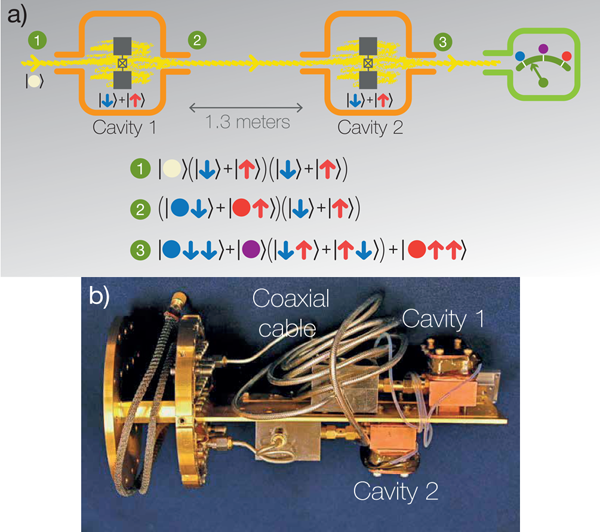

Both the Berkeley results and recent results from Delft [2] represent truly tour de force experiments, combining essentially all of the recent breakthroughs in the field of superconducting quantum circuits into a single working package. As schematically illustrated in Fig. 1(a), both experiments rely on superconducting qubits [3]—two pads of aluminum linked by a Josephson junction—that are placed inside copper cavities. While the Delft researchers put both qubits in the same cavity, the Berkeley experiment used two qubits in distinct cavities separated by meters of copper coaxial cable, although the limited space required that cable to be curled up so that the two cavities were within a few centimeters, as shown in Fig. 1(b). A true separation of more than a meter would help to close a logical loophole for testing quantum locality with this apparatus using Bell’s inequality, but it would almost certainly not affect the results.

Rather than using a two-step, create-then-share, approach, both groups prepared an entangled state of two superconducting qubits by jointly measuring them in such a way that the outcome is, with probability, an entangled state. Such entanglement by measurement has also been demonstrated in atomic and solid-state systems using optical photons. But how can measurement produce entanglement when, in quantum mechanics, measurement typically destroys quantum coherence? The trick is simple and consists of designing the measurement in such a way that it cannot distinguish between all states that the system might occupy, only between different subsets of states. The experiment thus starts by preparing the system in a uniform coherent superposition of all possible states. Then, a measurement probabilistically yielding a result corresponding to one of those subsets will leave the system in a fully coherent superposition of the states within that subset, a superposition that can be entangled.

This is realized by Roch and colleagues by first preparing both superconducting qubits in a superposition of their two logical states, represented by colored arrows in Fig. 1. A microwave tone, with a frequency close to that of one of the modes of the cavities but far detuned from the qubit, is then sent to the first cavity. Representing the state of the microwave field by the color of circle, this step is labeled in Fig. 1. As it goes through the cavity and interacts with the qubit, the microwave tone picks up a phase shift that depends on the state of the qubit. This correlation between the qubit and the phase results in an entangled state of the qubit and the propagating microwave photons at the output of the first cavity, corresponding to step in Fig 1. Such qubit-photon states have already been well characterized experimentally [4]. Measuring the phase of the field at that point would reveal the qubit state and destroy this superposition, leaving the qubit in one of its basis states.

However, rather than being measured, the field is sent via the coaxial cable to another cavity containing the second qubit which is, until then, not entangled with the field. As before, after interaction with this second qubit, the field at the output of the second cavity acquires a qubit-state-dependent phase shift, see step in Fig. 1. Although the four possible states of the two qubits could, in general, be distinguished by a phase measurement, the Berkeley experiment is set up in such a way that the phase can take only one of three values. As illustrated schematically in Fig. 1, the phase will be different if both qubits are up , or both down . The phase will however take the same value (purple circle in the figure) if the qubits have opposite states . Since the qubits were initially in a coherent superposition, measurement of the phase will therefore probabilistically lead to the entangled state of the two remotely located qubits.

The degree of entanglement can be characterized by a quantity called the concurrence, which ranges from for separable states to for perfectly entangled states. Roch and coauthors find a concurrence of . This is significantly lower than what can be achieved by turning on and off direct interactions between qubits fabricated on the same chip [5,6] but is nevertheless a very encouraging start, especially because addressing technical problems such as losses and detection efficiency should increase this number to [1]. The Delft experiment measured a similar concurrence but took advantage of a feedback protocol to succeed in preparing an entangled states with probability.

An alternative remotely entangled state—a pair of photons propagating in distinct transmission lines on the same chip—has also recently been realized experimentally using the so-called Hong-Ou-Mandel effect [7]. Finally, Roch and co-workers also used the framework of quantum trajectories [8] to, in essence, “film” the entangled state as it is created by the measurement.

Both the Berkeley and the Delft experiments pave the way to quantum networks [10] in the microwave frequency range where both strong coupling to superconducting qubits [11] and large photon nonlinearities [12] are easily realizable. An important remaining challenge is to reduce losses between the two cavities, especially in components like circulators that are used to ensure directionality of the information transfer. However given that superconducting cables have essentially the same losses per meter as optical fiber, there is no reason to believe that more complicated networks cannot be realized.

References

- N. Roch, M. E. Schwartz, F. Motzoi, C. Macklin, R. Vijay, A. W. Eddins, A. N. Korotkov, K. B. Whaley, M. Sarovar, and I. Siddiqi, “Observation of Measurement-Induced Entanglement and Quantum Trajectories of Remote Superconducting Qubits,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 170501 (2014)

- D. Riste, M. Dukalski, C. A. Watson, G. de Lange, M. J. Tiggelman, Y. M. Blanter, K. W. Lehnert, R. N. Schouten, and L. DiCarlo, “Deterministic Entanglement of Superconducting Qubits by Parity Measurement and Feedback,” Nature 502, 350 (2013)

- J. Koch, T. M. Yu, J. Gambetta, A. A. Houck, D. I. Schuster, J. Majer, A. Blais, M. H. Devoret, S. M. Girvin, and R. J. Schoelkopf, “Charge-Insensitive Qubit Design Derived From the Cooper Pair Box,” Phys. Rev. A 76, 042319 (2007)

- C. Eichler, C. Lang, J. M. Fink, J. Govenius, S. Filipp, and A. Wallraff, “Observation of Entanglement between Itinerant Microwave Photons and a Superconducting Qubit,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 109, 240501 (2012)

- O.-P. Saira, P. Groen, J. J. Cramer, M. Meretska, G. de Lange, and L. DiCarlo, “Entanglement Genesis by Ancilla-Based Parity Measurement in 2D Circuit QED,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 070502 (2014)

- J. M. Chow, J. M. Gambetta, E. Magesan, S. J. Srinivasan, A. W. Cross, D. W. Abraham, N. A. Masluk, B. R. Johnson, C. A. Ryan, and M. Steffen, “Implementing a Strand of a Scalable Fault-Tolerant Quantum Computing Fabric,” arXiv:1311.6330v1 (2013)

- C. Lang, C. Eichler, L. Steffen, J. M. Fink, M. J. Woolley, A. Blais, and A. Wallraff, “Correlations, Indistinguishability and Entanglement in Hong–Ou–Mandel Experiments at Microwave Frequencies,” Nature Phys 9, 345 (2013)

- H. M. Wiseman and G. J. Milburn, “Quantum Measurement and Control,” (Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2009)[Amazon][WorldCat]

- K. W. Murch, S. J. Weber, C. Macklin, and I. Siddiqi, “Observing Single Quantum Trajectories of a Superconducting Quantum Bit,” Nature 502, 211 (2013)

- H. J. Kimble, “The Quantum Internet,” Nature 453, 1023 (2008)

- A. Blais, R.-S. Huang, A. Wallraff, S. M. Girvin, and R. J. Schoelkopf, “Cavity Quantum Electrodynamics for Superconducting Electrical Circuits: An Architecture for Quantum Computation,” Phys. Rev. A 69, 062320 (2004)

- G. Kirchmair, B. Vlastakis, Z. Leghtas, S. E. Nigg, H. Paik, E. Ginossar, M. Mirrahimi, L. Frunzio, S. M. Girvin, and R. J. Schoelkopf, “Observation of Quantum State Collapse and Revival due to the Single-Photon Kerr Effect,” Nature 495, 205 (2013)