Why Like Charges Attract

Two negatively charged beads floating in water repel one another, but not if they’re near a wall, according to experiments going back to 1994. This and similar puzzling results have led to a long list of complex theories attempting to explain the apparent attraction between like charges in some situations. Now, in the 4 December PRL, a team proposes a simple explanation for at least some of the results: Each bead is repelled by the charged wall, and as it moves away, it drags water–and its partner bead–along for the ride, in a flow that brings the beads together. The team’s computer simulations agree with experiments, and the theory seems to solve the mystery for at least one class of the surprising phenomena. But it remains unclear how other closely related results fit into the picture.

One set of experiments by David Grier and Amy Larsen of the University of Chicago in 1997 involved positioning a pair of 1-µm-diameter plastic beads in water at a series of separations using laser tweezers and releasing them many times. Grier and Larsen followed the particle positions with time after release, and found that for certain starting separations–and whenever the beads were close to the chamber’s glass bottom–the negatively charged beads moved toward one another. According to other experiments, large collections of like-charged beads in water can form “crystals” whose properties seem to require that the beads attract one another. The attraction of beads in these cases “completely stands knowledge of electrostatics on its head,” if taken at face value, says Michael Brenner of MIT.

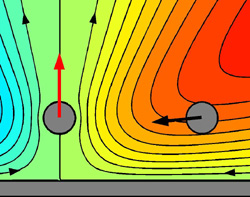

Brenner and graduate student Todd Squires of Harvard University realized that the apparent attraction in the Chicago experiments could be caused by movement of the beads away from the glass, which becomes negatively charged in water. That slight vertical motion might not have been picked up in the Chicago team’s automated experiments. From a small bead’s perspective, water is thicker than honey, and as a particle is pushed away from a surface, water is drawn behind it, from both sides, setting up a long-distance fluid flow that could pull in another particle, Squires and Brenner found. Imagine the amount of fluid flow caused by lifting a plate lodged at the bottom of a sink full of water, Squires suggests. The fluid flow is quite different for particles far from a surface.

Squires and Brenner worked out the equations and then ran computer simulations of the Chicago experiments. With just one undetermined parameter (the charge on the glass), their results agreed well with the experimental data. “This could very well settle a long-standing controversy,” says Grier, although “the jury’s still out” on the value of that one parameter.

According to Grier, most of the other experiments showing anomalous attraction between beads were done in equilibrium, with the beads in Brownian motion around their average positions. The new results don’t directly explain those cases, so there may be some other still unexplained mechanism operating. Some other experts are concerned that a single theory should cover both types of experiments. But David Weitz of Harvard says the paper gives “a very simple and elegant explanation” for the effect and accounts for the data better than any of the complex theories did. “Coulomb is still correct,” adds Weitz.

More Information

The Larsen/Grier experiments are in Nature (London) 385, 230 (1997).