Cells Go with the Crowd

Many biological cells can perform chemotaxis—sensing a chemical, or “chemoattractant,” and moving in the direction of increasing concentration. For example, white blood cells seek invaders, and embryonic cells follow biochemical cues during development. In some cases, only clusters of cells are capable of detecting a concentration gradient, not individual cells, but researchers don’t understand exactly how such “collective” chemotaxis works. Now a team led by Wouter-Jan Rappel of the University of California, San Diego, has developed a simple mathematical model for the process.

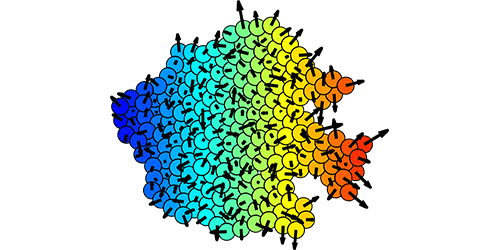

The model assumes that each cell has a fluctuating “polarity” that determines its direction and speed of motion. In the model equations, which are based on experimental observations, the polarity of a cell has a preference to point away from its neighbors, so that cells near the edges of a cluster want to move outward. But the equations also specify that the strength of this outward-moving tendency is proportional to the local concentration of the chemoattractant. So whichever edge experiences the highest concentration pulls the hardest and moves the cluster in that direction.

The researchers’ simulations and analytical results show that the model, which assumes no gradient sensing by single cells, produces chemotaxis for cell clusters. It also predicts the speed and direction of motion of a cluster and the effects of cluster shape, size, and orientation. The chemotactic velocity of a two-cell cluster, for example, depends on the pair’s orientation with respect to the concentration gradient, and the team proposes looking for this effect with real cells as a test of the model.

See a video from the paper that shows the simulated trajectories of 1-, 2-, 7-, and 19-cell clusters based on the authors’ model.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–David Ehrenstein