Topological Origami

Fold a flimsy sheet of paper in half and it becomes stiffer. Keep adding folds and the paper can be transformed into a rigid structure that retains its shape. New theoretical work shows that origami and kirigami (origami in which folds are accompanied by cuts) can be designed to be stiff at one end and floppy at the other by tuning the angles of the folds and the position of the cuts. The resulting constructions fall into one of two distinct topological phases with well-defined mechanical properties.

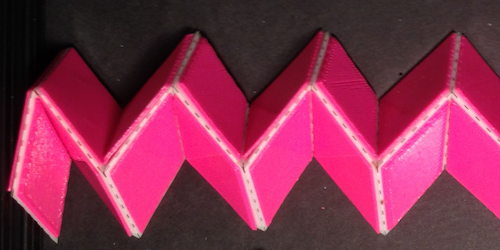

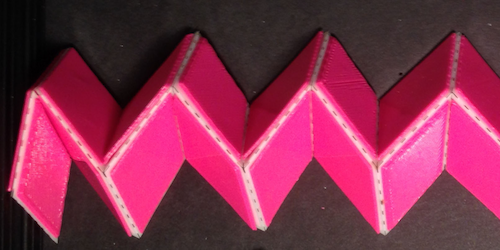

Bryan Gin-ge Chen, now at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, and colleagues connected a series of four-sided plastic units together, using hinges, to create a long, thin rectangular structure. This structure was squashed between two plates, forcing the material to spontaneously buckle like a concertina into a series of mountains and valleys. The group designed the cell patterns so that the rigidity of the origami was asymmetric along the length of the material. The folds of the resulting structures gradually transitioned from sharp (soft) at one end to shallow (rigid) at the other. The origami was classified into one of two topological phases depending on whether the left or right end was the softest. According to the authors’ predictions, larger square structures with asymmetric mechanical properties may also be designed, but only if sections of the pattern are completely cut out (kirigami). Without holes the folded structures would be uniformly soft at the structure’s edge and rigid in the middle. Chen and his colleagues suggest that their patterns could be used to design materials with tailored mechanical properties.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Katherine Wright