The Little Engine That Could

A car engine is an everyday example of a heat engine—a device that turns thermal energy into mechanical work. Scaled down to microscopic sizes, however, these devices can harness work from otherwise unwanted random thermal motion. But such stochastic heat engines are typically nonautonomous because they rely on an external control system to operate. As a result, they consume more energy than the work they produce. Chiara Daraio and Marc Serra-Garcia from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH), Zurich, and colleagues have now come up with a design for an autonomous, classical stochastic heat engine. The system could be an ideal toy model with which to study thermodynamics on the microscale.

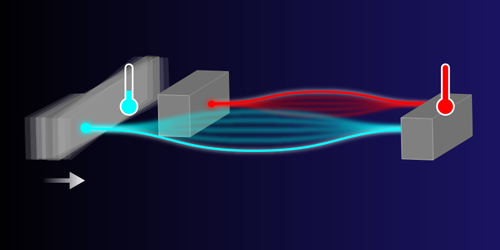

Their concept is analogous to that of a Stirling engine, which transforms heat into work by cyclic compression and expansion of a working fluid in contact with a cold and a hot thermal reservoir. It consists of a cantilever, two coupled ribbons (main and secondary), and one hot and one cold heat bath. The main ribbon is in contact with the cold bath and plays the role of the fluid: it heats up, expands, cools down, and compresses. The ribbon’s compression and expansion are driven by the push and pull of the cantilever, which uses energy that, via the secondary ribbon, comes from random thermal motion in the hot bath. Geometric nonlinearities in the ribbons regulate the coupling to the baths, allowing the main ribbon to heat up and cool down in synchrony with the cantilever motion and bypassing the need for an external control unit.

The researchers demonstrate that their engine works autonomously using a setup that is actually macroscopic in size. But using numerical simulations they show that the device is equally functional when shrunk to microscopic dimensions.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Ana Lopes

Ana Lopes is a Senior Editor of Physics.