Do alpha particles cluster inside heavy nuclei?

In the early part of the 20th century as physicists became aware of the existence of the nucleus, they speculated that the nucleus might be composed of particles [1]. This picture of the nucleus was eventually supplanted by the shell model, which considers nuclei to consist of neutrons and protons held together by an average potential generated by nucleon-nucleon interactions. This model is highly successful in describing both ground-state properties and excited states in nuclei under the assumption that the building blocks are individual protons and neutrons. However, in the 1960s, excited states in nuclei that comprise equal numbers of protons and neutrons, (e.g., and ) were identified that could not be described by the shell model, and it was suggested by Ikeda and others that these states could be associated with configurations composed of particles [2].

Alpha clustering in light nuclei is now well established [3]. These states are found at the decay thresholds in nuclei with neutron number equal to the atomic number ( ) and having total mass . In many instances, they are associated with chains of particles forming elongated, exotic shapes. For instance, the so-called Hoyle state in , whose existence is essential for the nucleosynthesis of carbon via the triple- process, is an example of an -cluster state. Because these configurations cannot be described by the shell model, so-called cluster models have been developed to characterize these states. In heavier nuclei, cluster states have not been observed. Nevertheless, the concept of particles existing inside the nucleus even in heavier systems is employed in order to describe decay, which is a common decay mode for heavy nuclei. For example, the -decay width for is an order of magnitude larger than predicted by the shell model. As a consequence, the ground-state properties of can only be reproduced by assuming both shell model and clusters states exist in . On the other hand, the shell model can describe reasonably well the known excited states in without invoking a cluster model. Thus it has been unclear whether states in exist that can be associated with a cluster configuration.

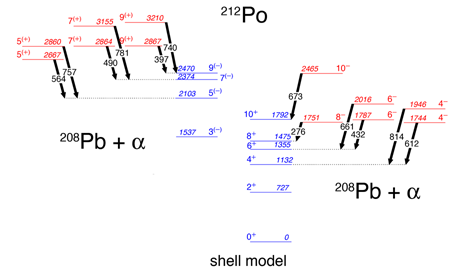

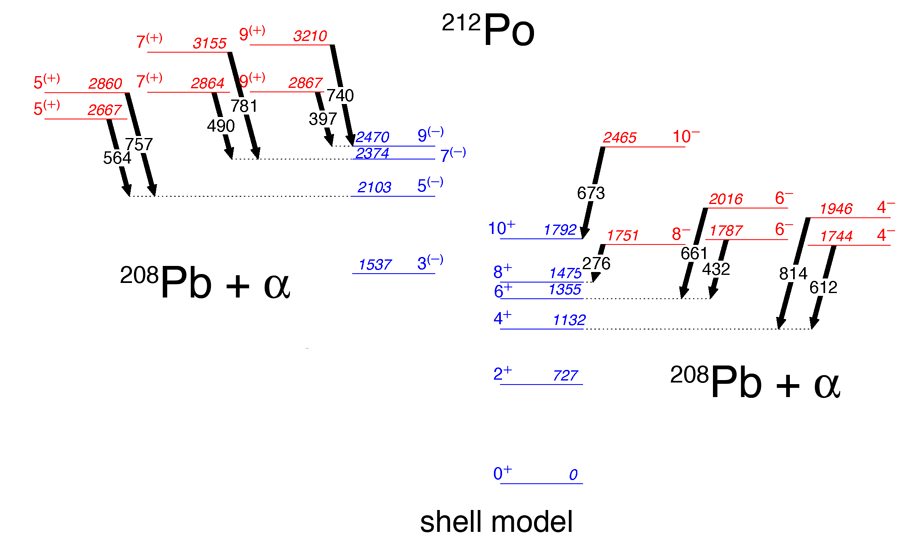

Now, in a paper in Physical Review Letters, Alain Astier and colleagues in France, Bulgaria, and Romania report a study identifying excited levels in whose properties can be understood with a model that associates these states with a configuration [4]. In order to search for such cluster states, the authors performed an experiment using an -transfer reaction where an - beam, supplied by the Vivitron tandem accelerator of IRES (Strasbourg), was incident on a foil. States in were populated when an particle was transferred from the beam to the target. The motivation for using this reaction was that if states associated with a configuration exist in , they would be preferentially populated using an −transfer reaction. Once the transfer takes place, the nucleus is left in an excited state and decays back to the ground state by the emission of rays. For this experiment, the emitted rays were detected by the Euroball IV -ray detector array [5], which consisted for this experiment of 71 Compton-suppressed high-purity germanium (HPGe) detectors. HPGe detectors are used because of their superior energy resolution when measuring energies of individual rays ( - FWHM energy resolution for - rays). The large number of detectors allowed for the collection in excess of events where three or more rays were detected in coincidence. These multicoincidence data allow for the construction of nuclear level schemes, which are mappings of excited levels in nuclei (see Fig. 1 ).

From the analysis of the data, previously unknown excited states have been identified in . Information obtained from -ray angular distributions, as well as transition selection rules, allows for the assignment of spin and parity to some of the newly observed levels. In addition, if rays are emitted by the nucleus while it is slowing down in the target, these transitions will have a non-Gaussian peak shape associated with them. By analyzing the line shape of a -ray transition as a function of detector angle relative to the velocity direction of the recoiling nucleus, the lifetime of the state emitting the ray can be deduced. For the reaction used in this experiment, rays emitted from states with lifetimes on the order of picosecond will exhibit line shapes.

Figure 1 shows a partial level scheme for . Known states associated with the ground state configuration (positive parity, even spin) and states coupled to an octupole vibrational excitation (negative parity, odd spin) are shown in blue. These states can be well understood within the framework of the shell model. In addition, a new set of states which have even-spin, negative parity (Fig. 1, right side) and a set of states with odd-spin, positive parity (Fig. 1, left side) have been identified. The former set of levels decay to members of the ground-state band, while the latter members decay to levels comprising the octupole vibrational band. These new states cannot be explained by the shell model. The connecting transitions between these new sets of states and the shell model states (represented as arrows in Fig. 1 ) have an electric-dipole multipolarity ( ), and, based on the lifetime measurements, they are relatively fast ( picoseconds).

The observed transitions are several orders of magnitude faster than one would expect between shell model states. Such “enhanced” transitions are rare in nuclei and are usually associated with nuclei having an asymmetric mass distribution. For example, electric-dipole transitions with similar decay strengths as measured in have been observed in some actinide nuclei, and these states have been associated with octupole deformed shapes [6]. As pointed out by Astier and collaborators, the configuration also has an asymmetric mass distribution. Using a model where they assumed the particle moves in the average field of the nucleus, they were able to show that the sequence of states assigned to the cluster configuration in Fig. 1 is what is expected when an particle vibrates against the core, however, the ordering of the states does not agree with expectations due to mixing with the shell model states.

While more theoretical work is needed to better quantify the observed spectrum of excited states, one could also imagine similar states existing in, for example, , which can be thought of as consisting of two particles outside a core. In this instance, the particles could behave coherently resulting in a similar set of states observed in or independently resulting in a more complex ordering of states associated with the cluster configuration.

References

- H. A. Bethe and R. F. Bacher, Rev. Mod. Phys. 8, 82 (1936)

- K. Ikeda, N. Takigawa, and H. Horiuchi, Prog. Theor, Phys. Suppl. Extra Number, 464 (1968)

- W. von Oertzen, M. Freer, and Y. Kanada-En’yo, Phys. Rep. 432, 43 (2006)

- A. Astier, P. Petkov, M-G. Porquet, D. S. Delion, and P. Schuck, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 042701 (2010)

- J. Simpson, Z. Phys. A 358, 139 (1997)

- I. Ahmad and P. Butler, Ann. Rev. Nucl. Part. Sci. 43, 71 (1993)