Peering into Jupiter

Attaining in situ data from planets in our solar system is an extremely difficult undertaking. Decades of planning go into designing missions, and careful consideration is made for what measurements should be made to yield the greatest scientific gain, and to make the cost and risks worthwhile. NASA’s Galileo mission, whose detailed planning began in 1970s, studied the Jovian system from 1995 to 2003. The Galileo entry probe was released from the main spacecraft, and plummeted into Jupiter’s atmosphere at on December 7, 1995. The data that was returned on the abundances of atoms and molecules in the planet’s atmosphere are unique constraints on our quantitative understanding of the interior structure, thermal evolution, and formation of the planet. Since Jupiter is our prototype giant planet, in a class that now numbers nearly “gas giants” in other planetary systems, this data is even more valuable than it was years ago. In a recent work in Physical Review Letters [1], Hugh Wilson and Burkhard Militzer from the University of California at Berkeley, US, have used an ab initio calculation of the mixing properties of noble gases under extreme conditions to explain one of the more curious measurements from the Galileo probe—the low abundances of the two lightest noble gases.

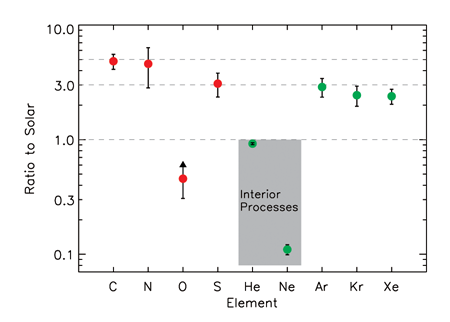

Jupiter is composed mostly of and , like the Sun. However, we can look at the enhancements or decrements in the abundances of the atoms more massive than (“metals” in astronomical parlance), compared to the measured abundances in the Sun and meteorites, to give us clues about the formation and interior physics of the planet itself. The probe stopped returning data at a pressure of only bars, while most of the planet is at significantly higher pressure, in the range – ( – ). However, efficient convection is expected to dominate in the interior, homogenizing the composition of the vast - envelope. Data from the Galileo probe showed that of the nine elements measured, six were enhanced by factors of to times that of the Sun [2–4] (see Fig. 1). These included the noble gases , and the abundant elements , and . Oxygen was depleted by a factor of , but a detailed visual and computational study of the probe entry point shows that it entered through one of the anomalously dry regions that make up a few percent of Jupiter’s visible surface [5]. The in situ measurements allow precise models to be devised of the composition of the solid “planetesimals” that were incorporated into Jupiter during its formation.

The abundances of and were depleted, which is particularly odd, since the three other noble gases (which also do not participate in solar system chemistry) are enhanced by a uniform factor of . The depletion of was expected by some, since in the 1970s it was calculated that He should have a limited solubility in the liquid metallic hydrogen that makes up the bulk of Jupiter’s mass [6,7]. Recently, ab initio models yielded good agreement with this earlier work [8,9]. The pressure-temperature region where phase separation is expected to occur ( – , ) is barely accessible to experiment. The pure phase diagram has been sparsely explored with dynamic experiments, but has never been explored for , let alone for mixtures. If phase separates from the mixture, and coalesces to form droplets that rain down to deeper layers, this could deplete from layers above the rain region as well, due to homogenization of composition by convection [10]. The modest depletion in Jupiter’s atmosphere is strong evidence that phase separation has started in Jupiter and will continue for the lifetime of the planet.

The very strong depletion in has always been a bit curious. Just before Galileo arrived at Jupiter, Roulston and Stevenson [11] published a one paragraph abstract suggesting that would dissolve into the separated He droplets, and would also be lost to deeper layers. Indeed, this was exactly what was seen, but there has always been lingering dissatisfaction, since no details of this suggestion were ever published. How strong should the depletion be in this picture? Can it match observations? Would the heavy noble gases dissolve as well? If so, this would “contaminate” the measured noble gas abundance levels that theorists have been incorporating into detailed formation models.

Wilson and Militzer have now provided the foundation for understanding the Galileo probe measurements for and . has been shown to strongly prefer the -rich droplet phase, leading to the measured strong depletion in the normal -rich phase that makes up the visible atmosphere. A further detailed study of shows that it does not share this behavior, and that the atmospheric abundance of this atom is the planet’s “true” value. It would be worthwhile in the future to consider if other elements that were measured by the entry probe strongly prefer one phase over another. Perhaps an alternative to the “weather” explanation for the low abundance of oxygen could be found?

This work has applications far beyond Jupiter. Saturn, which is only of Jupiter’s mass and has a lower pressure and colder interior, should be much further into the pressure-temperature space of phase separation. Saturn has not had an entry probe, but difficult spectroscopic measurements indicate a larger atmospheric depletion of He than found in Jupiter, but the error bars are large [12]. The -rain in Saturn is calculated to be so prevalent in the planet’s deep interior that this planet-wide differentiation process explains the long-noted excess luminosity of the planet [13]. If a Saturn entry probe is finally sent, a much stronger depletion in , but a similar ratio of depletion between and compared to Jupiter, is expected. phase separation and corresponding depletion surely happens in several-gigayears-old Jovian planets found around other stars as well. We are gradually beginning to understand these planets as a class of astrophysical objects. It is the wide-ranging study of these extrasolar planets, along with the complementary detailed study of the planets close to home, which will move us forward on this path.

References

- H. F. Wilson and B. Militzer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 121101 (2010)

- U. von Zahn, D. M. Hunten, and G. Lehmacher, J. Geophys. Res. 103, 22815 (1998)

- P. R. Mahaffy, H. B. Niemann, A. Alpert, S. K. Atreya, J. Demick, T.M. Donahue, D.N. Harpold, and T. C. Owen, J. Geophys. Res. 105, 15061 (2000)

- M. H. Wong, P. R. Mahaffy, S. K. Atreya, H. B. Niemann, and T. C. Owen, Icarus 171, 153 (2004)

- A. P. Showman and A. P. Ingersoll, Icarus 132, 205 (1998)

- D. J. Stevenson, Phys. Rev. B. 12, 3999 (1975)

- D. J. Stevenson and E. E. Salpeter, Astrophys. J. Supplement Series 35, 221 (1977)

- M. A. Morales, E. Schwegler, D. Ceperley, C. Pierleoni, S. Hamel, and K. Caspersen, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 1324 (2009)

- W. Lorenzen, B. Holst, and R. Redmer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 115701 (2009)

- D. J. Stevenson and E. E. Salpeter, Astrophys. J. Supplement Series 35, 239 (1977)

- M. S. Roulston and D. J. Stevenson, Eos 76, 343 (1995)

- B. J. Conrath and D. Gautier, Icarus 144, 124 (2000)

- J. J. Fortney and W. B. Hubbard, Icarus 164, 228 (2003)

- K. Lodders, H. Palme, and H. Gail, arXiv:0901.1149