Particles go with the flow

When dropping small particles into a turbulent fluid, we know from daily experience that the particles will be swept up in the swirling eddies and vortices of the fluid motion. But how will the particles be arranged in the flow, and does the addition of these particles smooth out the flow or make it more turbulent? These questions not only have industrial and technological implications, but are at the heart of our understanding of turbulence. It is also a puzzle that has resisted conventional fluid dynamics analysis. Now, in a paper published in Physical Review Letters, Tanaka and Eaton [1] of Stanford University have scrutinized a set of experimental measurements of particle motion in turbulent flows and find that a new dimensionless parameter, the particle momentum number Pa, can be used to assess whether particles will enhance or attenuate the turbulence.

Understanding turbulence has been a longstanding challenge. The press release accompanying the 1982 Physics Nobel Prize awarded to Kenneth G. Wilson for his theory of critical phenomena [2] cited “fully developed turbulence” as a prime example of an important and yet unsolved problem in classical physics. Mathematically, turbulence is described by the Navier-Stokes equations, and in 2000, the Clay Mathematics Institute called unlocking the secrets of these equations one of seven “Millenium Problems” and offered a $1 million prize for their solution [3]. Turbulence is such a difficult problem because of its multiscale character: Although the large length scales (of the order of some maximal outer length scale L, for example, the size of the container) can be many orders of magnitude larger than the inner length scales of order η (where the smoothing effects of viscosity become important), they are nevertheless strongly coupled to each other. The problem becomes worse the larger the Reynolds number Re (the ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces, for which high or low values characterize turbulent vs laminar flow, respectively) because L/η∼Re3/4. While the transition to turbulence occurs at a Reynolds number of several thousands (depending on the geometry), typical turbulent flow in the lab would have Re∼106 , and in the atmosphere, flows with Re∼109 can easily occur.

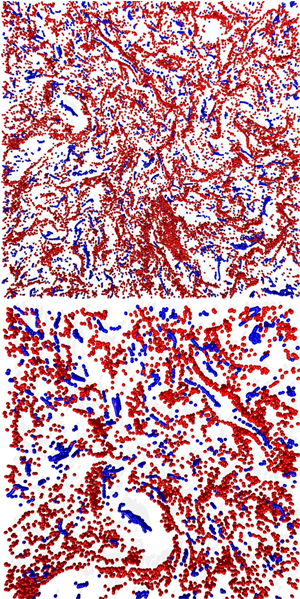

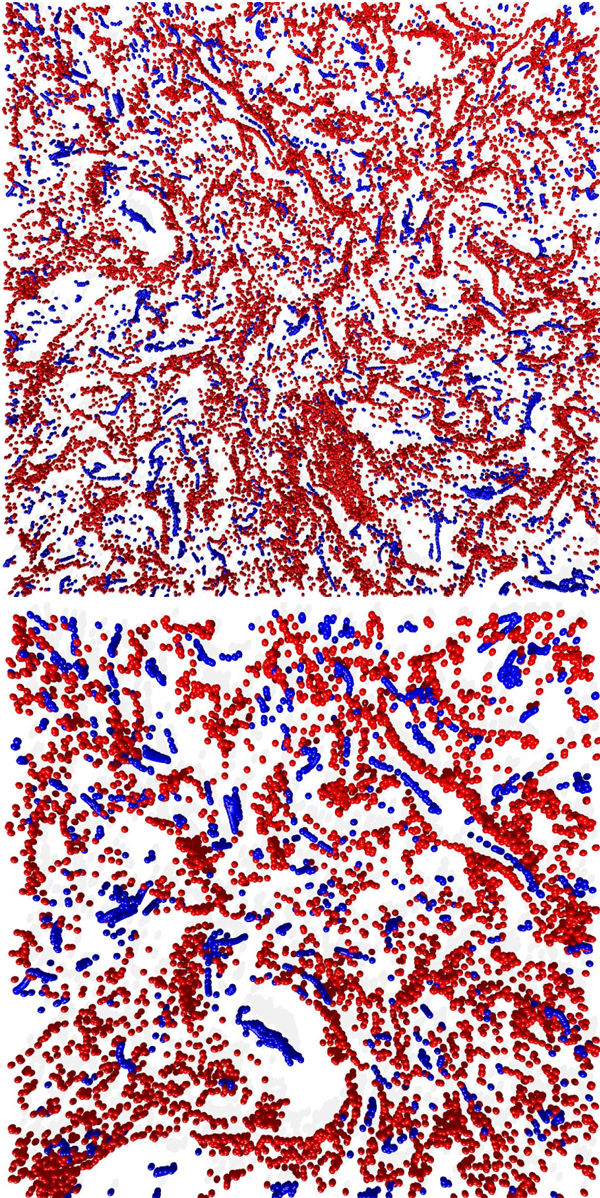

The problem obviously becomes further complicated when the turbulent flow transports particles—a situation that is omnipresent in nature and technology. Examples include aerosols, rain drops, snow flakes or dust particles in the atmosphere (and especially in clouds), plankton in the ocean, or catalytic particles and bubbles in process technology. For these situations it is a priori not clear how the particles distribute in the turbulent flow, which consists of vortices of various sizes—clearly, the distribution will be inhomogeneous (Fig. 1). Particles heavier than the carrier fluid are thrown out of the vortices due to centrifugal forces, whereas light particles accumulate close to the vortex cores—an effect that everybody can easily observe when stirring a glass of bubbly water. Neither is it a priori clear whether the particles enhance or attenuate the turbulence (see Ref. [4] for a classical review article). Take heavy particles in turbulent water: On one hand, one could argue that the particles thrown into still water will sink and thus excite some flow and therefore the flow should also be enhanced when starting with a turbulent flow situation. On the other hand, putting heavy particles in motion and rotation in turbulent flow costs energy and therefore the turbulence intensity should decrease.

One would hope to be able to predict the enhancement or attenuation of turbulence in the way common to fluid dynamics—by looking at the appropriate dimensionless numbers, such as the Reynolds number mentioned before. The classical dimensionless parameters for this problem would be the large scale Reynolds number Re of the turbulent flow, the density ratio of the dispersed particles and the carrier fluid, the volume concentration of particles, and the Stokes number St, which is the ratio of the particle relaxation time and the intrinsic timescale of the turbulent flow.

Tanaka and Eaton [1] have now mapped out 30 experimental data sets taken from literature with different combinations of Re and St, arguing that the particle concentration and the density ratio should only lead to a quantitative effect with regard to turbulence enhancement or attenuation. However, they did not find any systematic trend in the turbulence modification in this Re-St plane. Data sets showing either turbulent kinetic-energy attenuation or augmentation were seemingly randomly scattered over the Re-St plane, suggesting that the Stokes number is not the correct control parameter for turbulence modification.

This finding and their further dimensional analysis of the underlying Navier-Stokes equations with an extra forcing term due to the dispersed particles, led Tanaka and Eaton to introduce a new type of dimensionless parameter, which they call the particle momentum number Pa. One version of this parameter can be written as Pa=Re2St(η/L)3, which one would expect should scale as ∼Re-1/4St, given the aforementioned expression for L/η. Now, in the Re-Pa plane the 30 analyzed data sets do fall into different groups: For Pa<103 the turbulence is augmented, for 103<Pa<105 it is attenuated, and for Pa>105 it is augmented again. This finding is surprising as (i) the dependence of the turbulent kinetic energy is nonmonotonic as a function of Pa, and (ii) one would assume that a simple rescaling of St with Re-1/4 would not all of a sudden lead to a grouping of the data sets.

Without any doubt this paper will trigger much further analysis. Presently, only data sets that show at least 5% attenuation or augmentation have been included in the study, in order to overcome experimental inaccuracies. I would expect the relative inaccuracies of the turbulent kinetic-energy modification to be smaller in numerical simulations of two-way-coupled point-particles in Navier-Stokes turbulence, such as those done in Refs. [5–8], where the particles act back on the flow, supplying an additional driving mechanism. Although the Reynolds numbers achieved in such simulations are considerably smaller than those in the data analyzed by Tanaka and Eaton [1], they would allow calculation of three-dimensional plots of the turbulent kinetic-energy modification as a function of Re and Pa, from which systematic trends could be derived. The gap between numerical simulations and experiment could be narrowed by extending Tanaka and Eaton’s analysis of experimental data towards smaller Reynolds numbers. Another extension of the parameter space would involve particles lighter than the carrier fluid, such as bubbles in turbulent flow, for which a wealth of numerical [9,10] and experimental [11,12] data on the energy modification exist. Tanaka and Eaton’s work thus gives hope that we can finally obtain order from the mist of turbulent data points on dispersed multiphase flow.

Acknowledgments

I thank Enrico Calzavarini (Ecole Normale Supérieure, Lyon, France) for providing Fig. 1 and for many stimulating discussions over the years. Moreover, I would like to thank the Fundamenteel Onderzoek der Materie (FOM) for continuous support.

References

- T. Tanaka and J. K. Eaton, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 114502 (2008)

- http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1982/press.html

- http://www.claymath.org/millennium/Navier-Stokes_Equations

- R. Gore and C. T. Crowe, Int. J. of Multiphase Flow 15, 279 (1989); S. Elghobashi, Appl. Sci. Res. 52, 309 (1994)

- K. D. Squires and J. K. Eaton, Phys. Fluids A 2, 1191 (1990)

- S. Elghobashi and G. C. Truesdell, Phys. Fluids A 5, 1790 (1993)

- O. A. Druzhinin and S. Elghobashi, Phys. Fluids 10, 685 (1998)

- A. Ferrante and S. Elghobashi, Phys. Fluids 15, 315 (2003)

- E. Climent and J. Magnaudet, Phys. Rev. Lett. 82, 4827 (1999)

- I. M. Mazzitelli, D. Lohse, and F. Toschi, Phys. Fluids 15, L5 (2003)

- M. Lance and J. Bataille, J. Fluid Mech. 222, 95 (1991)

- J. Rensen, S. Luther, and D. Lohse, J. Fluid Mech. 538, 153 (2005)

- E. Calzavarini, M. Cencini, D. Lohse, and F. Toschi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 101, 084504 (2008)

- E. Calzavarini, M. Kerscher, D. Lohse, and F. Toschi, J. Fluid Mech. 607, (2008)