Sonic booms at kelvin

The Relativistic Heavy Ion Collider (RHIC), now in its eighth year of running, provides the means to create and study “super-hadronic” matter, whose energy density far exceeds that of the interior of a proton. At temperatures above , the nucleons melt into a plasma of quarks and antiquarks. The super-hadronic state created in a central collision of the 100-GeV Au ions lasts about , before cooling to the point where thousands of hadrons appear and are finally emitted approximately after the initial collision. Strong collectivity dominates phenomena at RHIC. The angular distribution of emitted particles, arising from the anisotropic pressure gradients caused by the elliptic anisotropy of the initial collision region in noncentral collisions, is consistent with nearly zero viscosity and has inspired the phrase “perfect fluid” [1,2]. Hydrodynamic behavior is especially remarkable for glancing collisions where the transverse diameter is only and the quasiparticle density is . In a paper in Physical Review C, R. B. Neufeld and B. Müller (Duke University) and J. Ruppert (Goethe University and McGill University) analyze whether one of the most dramatic hydrodynamic phenomena—acoustic shock waves (sonic booms) and the resulting Mach cones—can occur in the quark matter produced at RHIC [3].

Hydrodynamic behavior implies low viscosity. Primarily based on the analysis of elliptic flow at RHIC, an upper limit for the viscosity-to-entropy ratio of the partonic phase (i.e., the fluid of quarks and gluons) appears to be [4], while theoretical limits suggest a lower limit of [5]. Even at the upper limit, the viscosity of the partonic liquid would be the lowest of any known liquid. The unique nature of the partonic fluid derives from the strong coupling and from the large number of partonic degrees of freedom. Whereas a relativistic gas of electrons is made of two species (spin-up and spin-down), partons effectively have species once one accounts for quarks and gluons with degeneracies related to spin, particle-antiparticle, flavor, and color. A partonic fluid thus has dozens of strongly interacting quasiparticles within a volume defined by the thermal wavelength.

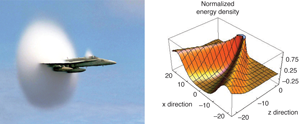

The existence of Mach cones would be even more surprising in such small systems [6,7]. Mach cones originate from supersonic disturbances (Fig. 1, left) with sound waves being emitted at the Mach angle , for velocity in a medium with sound speed . In this case, the disturbance is a jet moving with velocity (where is the speed of light) and the speed of sound is . “Jets” refers to partons created by hard collisions during the initial touching of the nuclei. Jets occur infrequently and have energies many times larger than the partons in the thermalized medium. Since jets are strongly damped in the RHIC environment [8,9], the observation of a high-energy jet signals that the production point was near the surface. From momentum conservation, every jet is accompanied by an away-side jet, which in a proton-proton collisions is roughly 180° opposite the triggering jet. However, due to strong jet quenching, the initially supersonic away-side jet is absorbed into the medium in heavy-ion collisions. Double peaks in the away-side spectrum are observed at appropriate angles for a Mach cone [10,11]. The away-side jet is absorbed by the medium, and the remnants produce the double-peaked structure in the opposite direction, consistent with the shape expected from a Mach cone.

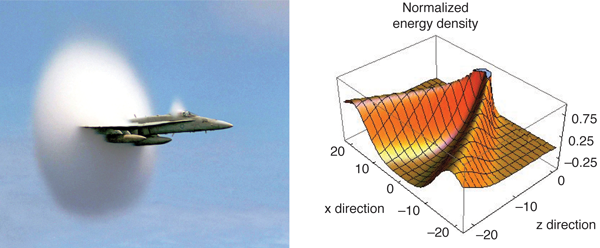

The paper by Neufeld et al. [3] addresses whether the concept of a Mach cone is applicable for jets at RHIC. The hadron jet is treated as a driving source in the hydrodynamic equations of motion where the color fields generated by the jets impart energy and momentum to the fluid. The source term is proportional to the square of the QCD color field and extends a distance determined by the color screening length fm (also known as the inverse Debye mass). Whereas an idealized Mach cone is driven by a point-like disturbance, Neufeld et al. [3] solve for the detailed space-time structure of the source term, with the screening length providing the critical length scale, which determines the sharpness of the pulse (Fig. 1, right). This picture corresponds to collisional energy loss, whereas radiation is considered to be the greater source of the stopping.

The authors consider the response of the fluid to the perturbing source, then follow the medium assuming viscous equations of motion. The second length scale that appears is the length over which the sound modes of wave number decay, which is a function of shear viscosity , and the energy density and the pressure of the medium . The characteristic wave number is determined by the distance over which the jet travels before quenching. When falls below the characteristic size of the medium, damping and spreading of the wave become important, and if comes close to the screening length, the structure of the shock becomes completely washed out. The sonic perturbation is strongly damped if is near the upper limit , but propagates smoothly at the Kovtun-Son-Starinets [5] limit, . Thus, validation of shock waves would provide the strongest and most dramatic evidence for the nearly perfect nature of the partonic fluid created at RHIC.

The new work by Neufeld et al. [3] demonstrates that shock waves should exist at RHIC, but by no means proves that the observations at RHIC are due to Mach cones. A host of other explanations exist: Cerenkov radiation [12,13], large-angle gluon radiation [14,15], deflection by collective radial flow [16], and path-length dependent energy loss [17]. First, the cone-like correlations involved particles with momenta near 1–2 GeV—several times higher than the thermal momentum. Since Mach cones are a hydrodynamic phenomena, the structure needs to be verified for particles with thermal energies. Furthermore, realistic three-dimensional models of the partonic fluid evolution need to be developed. It is not yet known how collective expansion and the traversal through the hadronic phase (which has a much slower speed of sound) modifies the behavior of the Mach cone, or modifies any of the other explanations listed above.

References

- D. Teaney, J. Lauret, and E. V. Shuryak, Phys. Rev. Lett. 86, 4783 (2001)

- P. Huovinen, Phys. Lett. B 503, 58

- R. B. Neufeld, B. Müller, and J. Ruppert, Phys. Rev. C 78, 041901 (2008)

- P. Romatschke and U. Romatschke, Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 172301 (2007)

- P. K. Kovtun, D. T. Son, and A. O. Starinets, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 111601 (2005)

- H. Stoecker , Nucl. Phys. A 750, 121 (2005)

- J. Casalderrey-Solana, E. V. Shuryak, and D. Teaney, J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 27, 22 (2005); Nucl. Phys. A 774, 577 (2006)

- J. Adams et al. (STAR Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 072304 (2003)

- S. S. Adler et al. (PHENIX Collaboration), Phys. Rev. Lett. 91, 072303 (2003)

- B. I. Abelev et al. (STAR Collaboration), arXiv:0805.0622

- N. N. Ajitanand (PHENIX Collaboration), AIP Conf. Proc. 842,122 (2006)

- I. Dremin, Nucl. Phys. A 767, 233 (2006)

- V. Koch, A. Majumder, and X-N. Wang, Phys. Rev. Lett. 96, 172302 (2006)

- A. D. Polosa and C. A. Salgado, Phys. Rev. C 75, 041901 (2007)

- I. Vitev, Phys. Lett. B 630, 78 (2005)

- N. Armesto, C. A. Salgado, and U. A. Wiedemann, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 242301 (2004)

- C. B. Chiu and R. C. Hwa, Phys. Rev. C 74, 064909 (2006)