Pulsars Probe Early Universe

The early Universe’s vacuum may have abruptly changed its state—like a liquid turning solid. Such a phase transition, which is predicted in certain “beyond-standard-model” particle physics theories, would have bathed the Universe in gravitational waves. These transition-induced waves might be detectable with pulsars, whose signals are predicted to fluctuate in the presence of gravitational waves. Two separate groups have now identified a hint of this fluctuation signature in their pulsar data, but they interpret the signature differently. The North-America-based NANOGrav Collaboration assumes the hint is real and derives from it possible transition parameters [1]. The Australia-based Parkes Pulsar Timing Array (PPTA) Collaboration assumes the hint is noise, allowing them to place new constraints on transition models [2]. The two collaborations are currently working on fusing their data, with the hope of uncovering a definitive gravitational-wave signature.

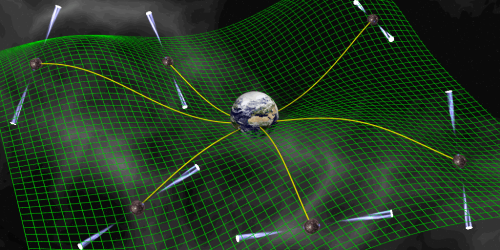

Pulsars are rotating neutron stars that emit beams of light. On Earth, we see these beams as flashes at extremely regular time intervals. Astronomers from around the world monitor these flashes, looking for timing fluctuations that would arise from gravitational waves passing between the pulsars and Earth. A year ago, the NANOGrav Collaboration detected a feature—a so-called common-spectrum process—in the timing fluctuations (see Cosmic Ringtones in Pulsar Data?). The team now finds that, if interpreted as a gravitational-wave signal, this feature is compatible with a strong cosmological phase transition at a low energy (less than 10 MeV).

The PPTA Collaboration has also detected a common-spectrum signal, but they interpret it as a systematic error, coming perhaps from intrinsic noise in pulsar flashes. They argue that the conclusive proof of gravitational waves is a correlation in the fluctuations of pulsars near to each other in the sky. That correlation has not been observed, allowing the PPTA team to place new limits on the strength of low-energy (1–100 MeV) cosmological phase transitions.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics Magazine based in Lyon, France.

References

- Z. Arzoumanian et al. (NANOGrav Collaboration), “Searching for gravitational waves from cosmological phase transitions with the NANOGrav 12.5-year dataset,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 251302 (2021).

- X. Xue et al. (The PPTA Collaboration), “Constraining cosmological phase transitions with the Parkes pulsar timing array,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 127, 251303 (2021).