Self-Repelling Species Still Self-Organize

Many biological processes depend on chemical reactions that are localized in space and time and therefore require catalytic components that self-organize. The collective behavior of these active particles depends on their chemotactic movement—how they sense and respond to chemical gradients in the environment. Mixtures of such active catalysts generate complex reaction networks, and the process by which self-organization emerges in these networks presents a puzzle. Jaime Agudo-Canalejo of the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization, Germany, and his colleagues now show that the phenomenon of self-organization depends strongly on the network topology [1]. The finding provides new insights for understanding microbiological systems and for engineering synthetic catalytic colloids.

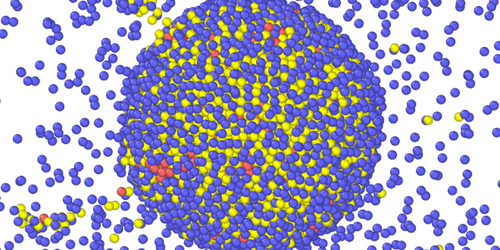

In a biological metabolic network, catalysts convert substrates into products. The product of one catalyst species acts as the substrate for another species—and so on. Agudo-Canalejo and his team modeled a three-species system. First, building on a well-established continuum theory for catalytically active species that diffuse along chemical gradients, they showed that systems where each species responds chemotactically only to its own substrate cannot self-organize unless one species is self-attracting. Next, they developed a model that allowed species to respond to both their substrates and their products. Pair interactions between different species in this more complex model drove an instability that spread throughout the three-species system, causing the catalysts to clump together. Surprisingly, this self-organization process occurred even among particles that were individually self-repelling.

The researchers say that their discovery of the importance of network topology—which catalyst species affect and are affected by which substrates and products—could open new directions in studies of active matter, informing both origin-of-life research and the design of shape-shifting functional structures.

–Rachel Berkowitz

Rachel Berkowitz is a Corresponding Editor for Physics Magazine based in Vancouver, Canada.

References

- V. Ouazan-Reboul et al., “Network effects lead to self-organization in metabolic cycles of self-repelling catalysts,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 131, 128301 (2023).