Cell Ordering May Depend on Nuclear Size

The geometric packing of biological cells often changes dramatically during organism development, but the mechanisms controlling such changes remain mysterious. In new experiments on human-lung cells growing on a spherical substrate, researchers have shown that the cells pack into increasingly well-ordered patterns as development proceeds [1]. The key driver of the change appears to be the rigidity of the cell nuclei—as a cell becomes larger, this rigidity has a greater effect on the cell’s shape, leading to a tighter packing with its neighbors. This understanding, the researchers suggest, may help in designing artificial bio-inspired materials such as smart fabrics or artificial skins.

Many human organs such as lungs, blood vessels, and intestines, have cells on their outer surfaces that perform important biological tasks. These surface cells actively coordinate their positions to form various tissue structures, says Ming Guo, a computational biologist at MIT. “But we still don’t know how they achieve this coordination among their relative positions,” he says.

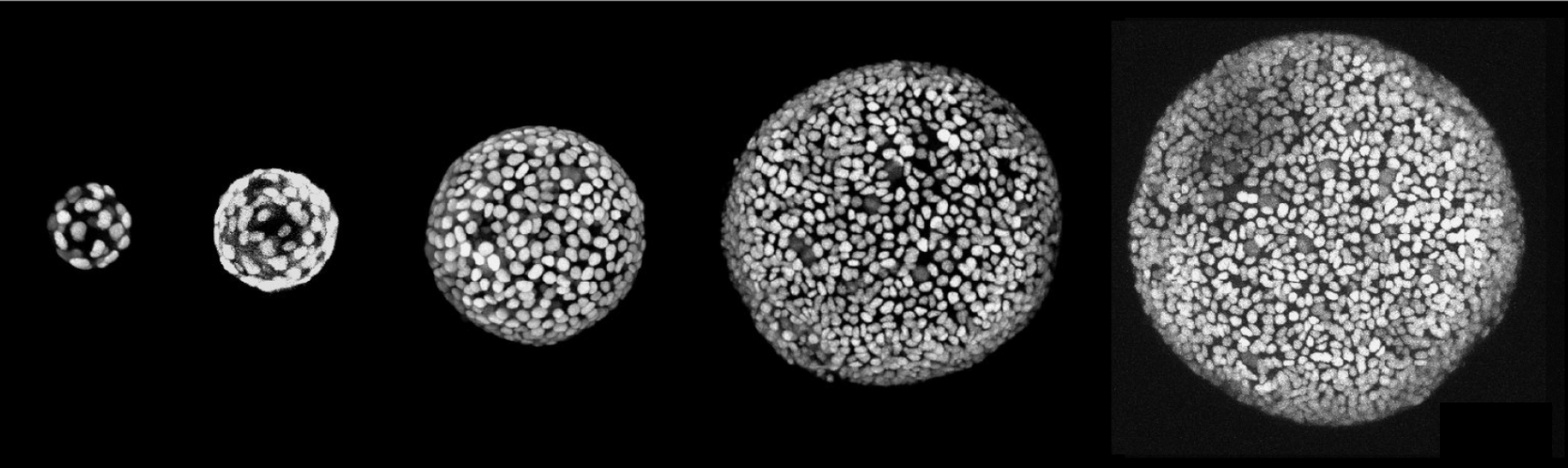

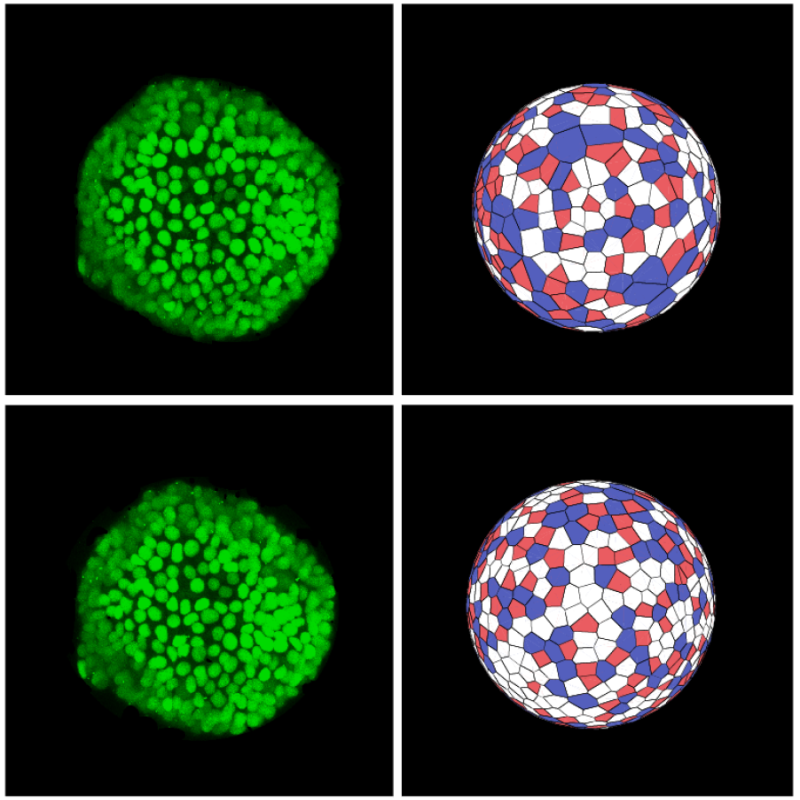

In an attempt to gain some understanding, Guo and colleagues undertook controlled experiments using alveolar epithelial cells, which form small air sacs called alveolospheres in the lungs. These air sacs are located at the ends of air tubes, where they allow oxygen and carbon dioxide to be exchanged between the air and the blood. To model these structures, the team grew monolayers of alveolar epithelial cells on the surfaces of spheres made of a nutrient gel. As the cells multiplied and developed, the artificial alveolospheres grew in size. The researchers measured individual cells using microscopy, and they tracked the relative size of the cell nuclei using a standard technique that involves green fluorescent proteins.

To represent the cellular network within an alveolosphere, the team created tiling patterns, where each polygon-shaped tile corresponded to a cell and the number of sides on a tile represented the number of nearest neighbors. The most common tile shapes were pentagons, hexagons, and heptagons. For small alveolospheres, pentagons were the dominant motif, but larger structures had a higher number of hexagons. This change to more hexagons—and thus to more uniformity in the cell-to-cell orientation—implied that the cell packing became more ordered as the alveolospheres grew bigger. The researchers also compared the observed network structures with those of a baseline model of random packing on a sphere and found evidence that the alveolosphere packing is influenced by some internal factor within the cells.

As to what that internal factor might be, Guo and his colleagues turned their attention to the cell nucleus, as the nucleus is the largest cellular organelle in eukaryotic cells and is considerably more rigid than the rest of the cell interior. “Because of these properties, we wondered if cell nuclear size might play a major role in regulating the cell–cell distance and coordinating the packing pattern,” Guo says.

He adds that this hypothesis would be consistent with other findings. For example, he points to a recent study of fruit flies that shows that cell packing in the brain and in the eyes can be tighter if each cell has a higher fraction of its area occupied by its nucleus.

To test this idea further, the researchers undertook another set of experiments in which they applied pressure to the cells. The pressure compressed the squishy outer portions of the cells, while the stiffer nuclei remained roughly the same size. As a result, the relative sizes of the nuclei increased. At the same time, the packing of cells became more ordered. These observations indicate, Guo says, that cells with relatively large nuclei are more rigid and thus are more constrained in how they arrange with respect to their neighbors.

The team plans to follow up this work with an investigation into whether this packing behavior might have an influence on biological function, such as the maturation of alveolospheres. Guo also sees potential technological opportunities in mimicking the packing behavior of cells. For example, this work might benefit the design of wearable electronics, where engineers need to tile electronic components efficiently onto curved human bodies.

“This research is a beautiful example of how the physics of packing is so important in biological systems,” says physicist Peter Yunker of the Georgia Institute of Technology. He says the researchers introduce the idea that cell packing can be controlled by the relative size of the nucleus, which “is an accessible control parameter that may play important roles during development and could be used in bioengineering.”

–Mark Buchanan

Mark Buchanan is a freelance science writer who splits his time between Abergavenny, UK, and Notre Dame de Courson, France.

References

- W. Tang et al., “Topology and nuclear size determine cell packing on growing lung spheroids,” Phys. Rev. X 15, 011067 (2025).