Microsoft’s Claim of a Topological Qubit Faces Tough Questions

Much of the oxygen at the American Physical Society’s Global Physics Summit in Anaheim, California, was taken up by discussions of “topological qubits.” These quantum devices are theorized to be much less error prone and easier to scale up than other qubit technologies, but building one has been far from easy. Researchers from the Microsoft Azure Quantum team recently hinted that they had a working topological qubit, and yesterday the team’s leader, Chetan Nayak, presented their evidence at a high-octane session at the Summit. Many physicists attending the talk, however, expressed doubts about the claim.

Nayak’s presentation came in the wake of a controversy involving a Microsoft announcement last month. Following a Nature publication [1], Microsoft issued a press release describing the realization of the world’s first chip powered by topological qubits, which “could lead to quantum computers capable of solving meaningful problems in years, not decades.” However, this claim went beyond what was presented in the peer-reviewed material—Nature’s editorial team wrote in a note that the results do not represent evidence for topological modes, but the research offers a platform for manipulating such modes in the future (see Research News: Experts Weigh in on Microsoft’s Topological Qubit Claim). At the time, Nayak said the evidence would be offered by his presentation at the Summit.

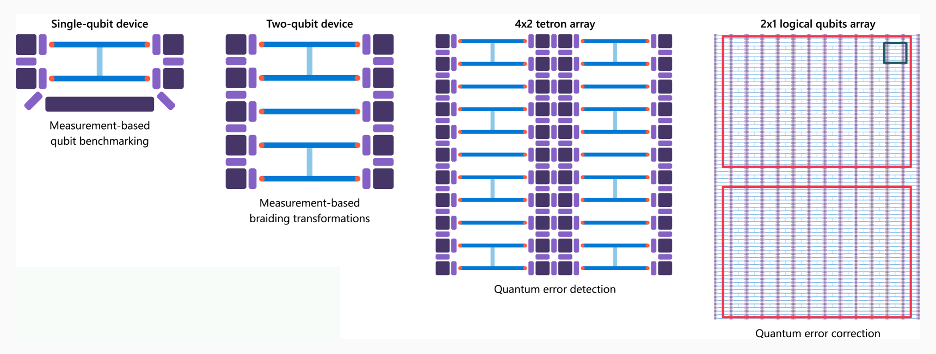

Understandably, his talk attracted a lot of attention: “Microsoft” and “Chetan Nayak” were the top two searches in the Summit’s program according to APS staff’s analysis of the 14,000 attendees’ online activity. In a large hall packed to capacity, Nayak presented his team’s new data on Microsoft’s “tetron” qubit, an H-shaped structure involving two nanowires connected by a superconducting bridge (Fig. 1). The wires are designed to host Majorana zero modes (MZMs), solid-state versions of Majorana particles, which condensed-matter researchers have attempted to detect for well over a decade.

MZMs are collective particle-like excitations predicted to exist at the boundaries of certain superconductors. Their relevance for quantum computing lies in the possibility of building qubits that encode quantum information in MZMs, which are inherently stable thanks to their “topological features.” Such topological qubits would be robust against environmental disturbances and thus much less error prone than conventional qubits—implying a tremendous simplification of the hardware required to build a useful quantum computer.

In the tetron device, MZMs are expected to appear at the four ends of the H-shaped structure. To test for the presence of these modes, Microsoft’s researchers applied the so-called “topological gap protocol (TPG),” a measurement and analysis procedure designed to ferret out MZM signals while ruling out spurious origins linked to imperfections, material disorder, and other nontopological, or trivial, effects [2]. Using this protocol, Nayak and his colleagues found experimental conditions, such as the strength of an applied magnetic field, under which both wires in the tetron passed the protocol.

Nayak then presented data on the qubit behavior of the tetron. In the device, 0 and 1 qubit states correspond to states of the coupled nanowires with different “parity.” Parity here is related to having an odd or even number of charges in the wires, which depends on the presence of MZMs. The team carried out different measurements to establish qubit behavior. In particular, through so-called “X” measurements, they sought to produce quantum superpositions of 0 and 1 states—the litmus test for quantum bits. Nayak showed a noisy curve that, after some processing, revealed a signal oscillating between two X values. Bimodal signals are expected to arise from quantum interference effects in the qubit. (Nayak acknowledged that “you can’t see [the bimodal signal] with the naked eye.”)

Many physicists in the audience questioned what the signals implied. The noise in the X measurements was an issue for condensed-matter-physicist Eun-Ah Kim of Cornell University. “I would have loved to see the signal jumping out at me,” she says, but wasn’t convinced the data offered signatures of qubit behavior. Javad Shabani, an expert on quantum materials and devices at New York University, agrees. “It might be some sort of a qubit, but they can’t control it. And I don’t yet see evidence that it’s topological,” he says. Caltech theorist Jason Alicea says there is value in establishing those measurements as tools for characterizing these architectures. “But I feel pretty strongly that there should be a much higher threshold for claiming the discovery of a topological qubit,” he adds.

In an earlier talk at the Summit, one physicist raised a fundamental objection to the TGP used by Microsoft to establish that their devices host MZMs. “The gap protocol is flawed,” said Henry Legg of the University of St Andrews, UK. Presenting an analysis he posted on arXiv, he argued that the protocol produces results that depend on measurement choices and input parameters, rather than on underlying device properties, and is likely to deliver “false positives,” that is, tag trivial phases as topological. He added that the protocol can’t detect a superconducting gap—which is necessary for the parity measurements. “The foundations to build a topological qubit aren’t there, and anyone claiming they have built one today is selling a dangerous fairy tale,” he concluded. Microsoft’s researcher Roman Lutchyn stood up and objected to Legg’s conclusions. He concedes that the TGP does deliver false positives, but he says that it does so with a negligible likelihood. “We stand behind the results of our papers,” said Lutchyn. “The [topological gap] protocol has merit, and the concerns have merit. My hope is that some of this criticism will help find ways to improve things,” says Alicea.

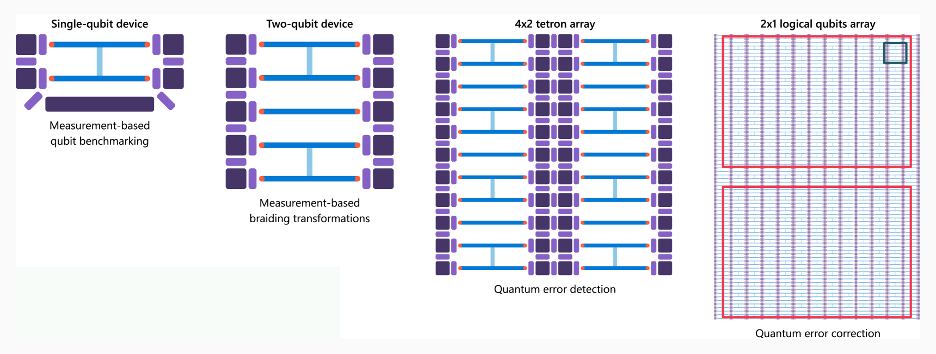

Nayak doesn’t dismiss the critical arguments: “I have never felt that there’d be one moment where everyone would be fully convinced.” But he says that an increasing number of researchers are convinced by Microsoft’s results. The team’s confidence, he says, comes from having a deep understanding of these devices, the materials, and the characterization techniques—layers of information that people not involved in the work may not appreciate. (He acknowledges that Microsoft isn’t able to share some relevant, proprietary information.) He foresees a number of advances in device fabrication—such as reducing disorder and improving the superconducting materials—that should lead to cleaner signals and offer prospects for larger-scale devices (Fig. 2) [3]. “As the devices progress you end up stress testing our understanding more and more,” he says.

Shabani says that different kinds of experiments—such as those observing the fusion of pairs of MZMs—are needed to convince him that Microsoft has topological devices. According to Kim, this research direction is still very young. But the potential features of a topological-qubit processor—robustness to errors and a competitive advantage in scaling up—are a great motivation to pursue it. “Reducing errors will require increasing the ‘topological gap,’ which is a huge engineering and materials science challenge,” she says. “Building topological qubits is a worthwhile goal, and we should all root for it,” says Alicea. The approach pursued by Microsoft faces enormous difficulties but “it’s still the best path we have in the near term,” he says. Shabani added that Microsoft’s chances of success would be much greater if it engaged more with the scientific community through collaborations.

–Matteo Rini

Matteo Rini is the Editor of Physics Magazine.

References

- Microsoft Azure Quantum, “Interferometric single-shot parity measurement in InAs–Al hybrid devices,” Nature 638, 651 (2025).

- D. I. Pikulin et al., “Protocol to identify a topological superconducting phase in a three-terminal device,” arXiv:2103.12217.

- D. Aasen et al., “Roadmap to fault tolerant quantum computation using topological qubit arrays,” arXiv:2502.12252v1.