Artificial magnetism for ultracold atoms

Recent progress in cooling and trapping of atoms has stimulated intense studies of the physical properties of the atomic Bose-Einstein condensates (BECs) and the degenerate Fermi gases. These systems are formed typically at densities of atoms per and temperatures in the nano-Kelvin range. Much current research in atomic quantum gases is motivated by the possibility of simulating a variety of condensed-matter phenomena [1–4] such as the transition between a superfluid state and an insulating state. An advantage of using atomic systems is the high degree of control: One can relatively easily change the physical parameters of the system including the number of the trapped atoms, the shape of the trapping potential, and the strength of the atom-atom coupling.

On the other hand, the atoms forming the quantum gases are electrically neutral particles and there is no Lorentz force acting on them. Thus there is no direct analogy between the properties of the degenerate atomic gases and magnetic phenomena involving electrons in solids, such as the quantum Hall effect discussed in a recent Viewpoint [5]. Now, Yu-Ju Lin and colleagues at NIST in Gaithersburg, Maryland, report in Physical Review Letters an important experimental advance towards producing an artificial magnetic field for an atomic Bose-Einstein condensate [6].

The usual way to imitate the magnetic field in a cloud of electrically neutral atoms is to rotate the system [7–9]. In the rotating frame of reference the Hamiltonian for the atomic motion acquires a vector-potential-type term describing the Coriolis force. The latter has the same mathematical structure as the Lorentz force for a charged particle in a uniform magnetic field. Additionally, inertial effects push the atoms away from the center of the rotating cloud. When the rotation frequency approaches the frequency of the atomic trap, the trapping is canceled by the centrifugal effect and the problem reduces to the cyclotron motion of a charged particle in a constant magnetic field. Using this method it is possible to produce vortex lattices in the atomic Bose-Einstein condensates [1].

Limitations in the experimental techniques have so far prevented researchers from reaching higher artificial magnetic fields where cold atoms could enter the fractional quantum Hall regime. Furthermore, the method of rotation usually applies to atomic clouds confined by cylindrically symmetric traps with a small anisotropic rotating potential added [1,7–9]. However, there are important trapping configurations like atom chips [10] lacking axial symmetry. Therefore it is desirable to have alternative methods for producing artificial magnetic fields for cold atoms without rotation. For atoms trapped in an optical lattice, the artificial magnetic field can be generated by inducing an asymmetry in the atomic tunneling between the lattice sites [11–13]. To simulate a magnetic flux there should be a nonvanishing phase for the atomic transfer around an elementary cell of the lattice known as the Peierls phase.

It is possible to create an artificial magnetic field for cold atoms without a trapping lattice. In these proposals, several laser beams are used to induce transitions between different atomic internal states in a position-dependent manner [14–17]. The laser fields alter (“dress”) the internal atomic eigenstates, which become superpositions of the original atomic states. It is the position-dependence of these dressed eigenstates that changes the momentum operator to for the atomic center-of-mass motion in the internal state [18,19]. The appearing effective vector potential represents an atomic momentum associated with the internal dressed state. Adopting the adiabatic approximation, one can ignore transitions to other atomic levels. The atomic motion in the dressed state then becomes equivalent to a motion of a particle of a unit charge in the magnetic field . Several schemes have been proposed providing a nonzero effective magnetic field for electronically neutral atoms in the laser fields [15–17]. Yet up to now there has been no experimental evidence of generating the artificial magnetic field using methods other than rotation.

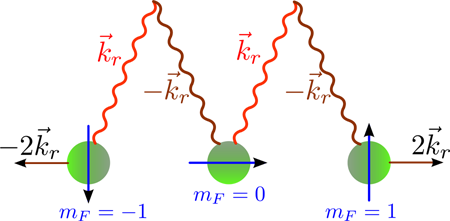

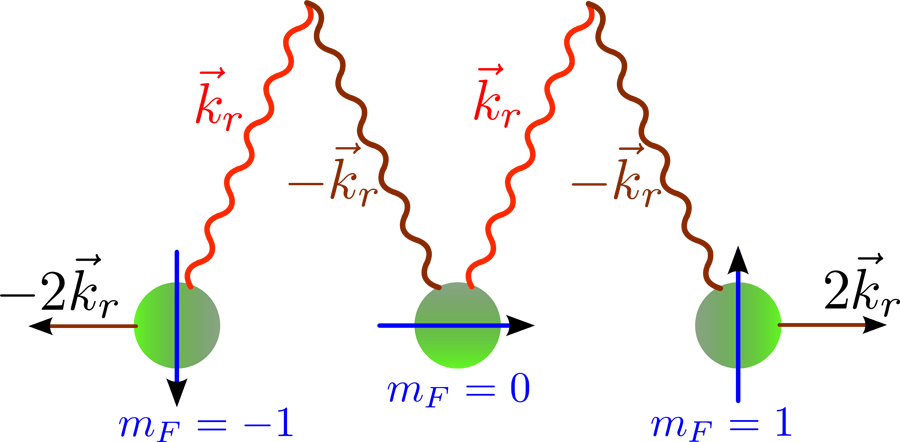

The experiment by Y.-J. Lin et al. [6] makes use of two counter-propagating laser beams that act on a of atoms characterized by a total spin . The atoms contain three magnetic ground states corresponding to different spin projections . Two laser beams induce the Raman transitions between the magnetic states with . The Raman process involves the absorption (emission) of a photon with a wave vector from one beam, and emission (absorption) of a photon from another beam with the opposite wave vector as shown in Fig. 1. As a result the laser beams couple the atomic states differing in spin projection and the linear momentum . In such a situation the laser-dressed atomic states are the superpositions of the combined spin and the center-of-mass motion states , where is the probability amplitude for the atom to have the spin projection . The states have a minimum energy at a certain wave vector , which depends on the detuning from the two-photon resonance. The corresponding momentum plays a role of a spatially uniform effective vector potential, shifting the origin of the atomic momentum. To simulate a Lorentz force , the effective vector potential should be spatially dependent and have a nonzero curl: .

An important ingredient of the experiment by Y.-J. Lin et al. [6] is the application of a real magnetic field in addition to the laser beams. The magnetic field removes the initial degeneracy of the spin levels with via the linear and quadratic Zeeman effects. By changing the strength of the magnetic field one can increase or decrease the two-photon detuning and thus alter the effective vector potential . Lin et al. have managed to transfer adiabatically the condensate atoms to the state with in the presence of the Raman laser beams and the magnetic field. Subsequently, the condensate was allowed to expand by removing the trap. The time-of-flight measurements have determined the atomic momentum as a function of the detuning , showing a good agreement with the theoretical calculations [6].

The vector potential produced in this way is uniform and thus corresponds to a zero effective magnetic field: [6]. The technique can be extended to generate nonuniform vector potentials for cold atoms. To accomplish this Lin et al. propose to apply a nonhomogeneous real magnetic field [6], resulting in the distance-dependent detuning . This provides the spatial dependence of the wave vector and leads to the nonzero effective magnetic field . In this way, it is a combination of the inhomogeneous real magnetic field and the counter-propagating laser beams that results in the artificial magnetic field and the Lorentz force acting on the electrically neutral atoms. The suggested scheme [6] can serve as an alternative to the previous proposals relying on the spatial variation of the laser beam profiles [15–17] or the optical lattices [11–13]. The future will show which of these approaches works better in creating the artificial magnetism.

If this could be achieved, we would have within our grasp the experimental realization of gauge potentials for cold atoms that would allow us to properly simulate a range of fascinating condensed-matter and high-energy physics. An important issue to be explored would be the creation of the non-Abelian gauge potentials for cold atoms [21–26]. The non-Abelian effects can appear if the atoms have degenerate dressed states and hence the atomic center-of-mass motion is described by a multicomponent wave function. The light-induced vector potential becomes then a matrix, the Cartesian components of which do not necessarily commute. By choosing the proper light fields, one can simulate a number of intriguing phenomena, such as formation of non-Abelian magnetic monopoles for cold atoms [22,26].

References

- I. Bloch, J. Dalibard, and W. Zwerger, Rev. Mod. Phys. 80, 885 (2008)

- M. Greiner, O. Mandel, T. Esslinger, T. Hänsch, and I. Bloch, Nature 415, 39 (2002)

- Z. Hadzibabic, P. Krüger, M. Cheneau, B. Battelier, and J. Dalibard, Nature 441, 1118 (2006)

- M. Greiner, C. A. Regal, and D. S. Jin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 110401 (2005)

- H. A. Fertig, Physics 2, 15 (2009)

- Y-J. Lin, R. L. Compton, A. R. Perry, W. D. Phillips, J. V. Porto, and I. B. Spielman, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 130401 (2009)

- K. W. Madison, F. Chevy, W. Wohlleben, and J. Dalibard, Phys. Rev. Lett. 84, 806 (2000)

- J. R. Abo-Shaeer, C. Raman, J. M. Vogels, and W. Ketterle, Science 292, 476 (2001)

- E. Hodby, G. Hechenblaikner, S. A. Hopkins, O. M. Marago, and C. J. Foot, Phys. Rev. Lett. 88, 010405 (2002)

- R. Folman, P. Krüger, J. Schmiedmayer, J. Denschlag, and C. Henkel, Adv. At. Mol. Opt. Phys. 48, 263 (2002)

- D. Jaksch and P. Zoller, New J. Phys. 5, 561 (2003)

- E. J. Mueller, Phys. Rev. A 70, 041603 (2004)

- A. S. Sørensen, E. Demler, and M. D. Lukin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 94, 086803 (2005)

- R. Dum and M. Olshanii, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 1788 (1996)

- G. Juzeliūnas and P. Öhberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 93, 033602 (2004)

- G. Juzeliūnas, J. Ruseckas, P. Öhberg, and M.Fleischhauer, Phys. Rev. A 73, 025602 (2006)

- K. J. Günter, M. Cheneau, T. Yefsah, S. P. Rath, and J. Dalibard, Phys. Rev. A 79, 011604 (2009)

- F. Wilczek and A. Shapere, Geometric Phases in Physics (World Scientific, Singapore, 1989)[Amazon][WorldCat]

- A. Bohm, A. Mostafazadeh, H. Koizumi, Q. Niu, and J. Zwanziger, The Geometric Phase in Quantum Systems (Springer, New York, 2003)[Amazon][WorldCat]

- M. Cheneau, S. P. Rath, T. Yefsah, K. J. Günter, G. Juzeliūnas, and J. Dalibard, Europhys. Lett. 83, 60001 (2008)

- K. Osterloh, M. Baig, L. Santos, P. Zoller, and M. Lewenstein, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 010403 (2005)

- J. Ruseckas, G. Juzeliūnas, P. Öhberg, and M. Fleischhauer, Phys. Rev. Lett. 95, 010404 (2005)

- J. Y. Vaishnav and C. W. Clark, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 153002 (2008)

- G. Juzeliūnas, J. Ruseckas, A. Jacob, L. Santos, and P. Öhberg, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 200405 (2008)

- N. Goldman, A. Kubasiak, P. Gaspard, and M. Lewenstein, Phys. Rev. A 79, 023624 (2009)

- V. Pietilä and M. Möttönen, Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 080403 (2009)