A Trapped Nanoparticle Listens In

In the mid 1980s, scientists at Bell Labs showed that the radiation pressure from a tightly focused beam of light was capable of holding microscopic particles stable in a trap [1]. Since then, the technique of using these “optical tweezers” has been instrumental in condensed matter and physical chemistry experiments, and an important diagnostic tool for fundamental and applied research [2,3]. Optical traps can manipulate dielectric objects ranging in size from nanometers to micrometers. With the introduction of so-called holographic optical tweezing methodologies, it is now possible to control trapped particles in three dimensions [4,5]. The technique is particularly useful for manipulating biological objects, because the optical field is nondestructive.

Most applications of optical trapping study the trapped particle in equilibrium—the particle is held at the trap minimum. But as the technique reaches new levels of precision, researchers are interested in seeing if an optically trapped particle could be used to measure nonequilibrium fluctuations in the particle’s environment. In a paper appearing in Physical Review Letters, Alexander Ohlinger and co-workers at Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich in Germany demonstrate an experiment where these fluctuations can be detected. They have constructed an optical trap that acts as a highly sensitive “ear,” capable of tracking the minute changes in position of an optically trapped gold nanoparticle as it is displaced from equilibrium by pressure waves from a nearby sound source [6].

The basis of an optical trap is a focused laser beam, which creates a strong electric field gradient that can grab and control various objects, including nanoparticles [7–9]. Radiation pressure provides an attractive or repulsive force on a particle, depending on the refractive index mismatch between the particle and the surrounding medium, which is often water or a solvent. The field gradient creates a three-dimensional potential well that limits the particle’s motion to roughly the focal volume of the focused laser beam. Scientists first showed they could trap particles a few tens of nanometers ( ) in size in all three dimensions in the early 1990s [7]; more recently a group at the University of Copenhagen used similar techniques to manipulate particles ranging in size from less than to a few hundred nanometers [8]. The same group showed that for nanoparticles with diameters less than , the trap stiffness (a parameter similar to the stiffness of a spring) is proportional to the volume of the particle [9]. In principle, the parameters describing the trapping potential well in optical tweezers, such as the position power spectra and strength of the trap, can be deduced, which offers a fairly simple approach to calibrate optical tweezers.

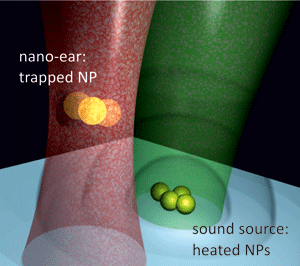

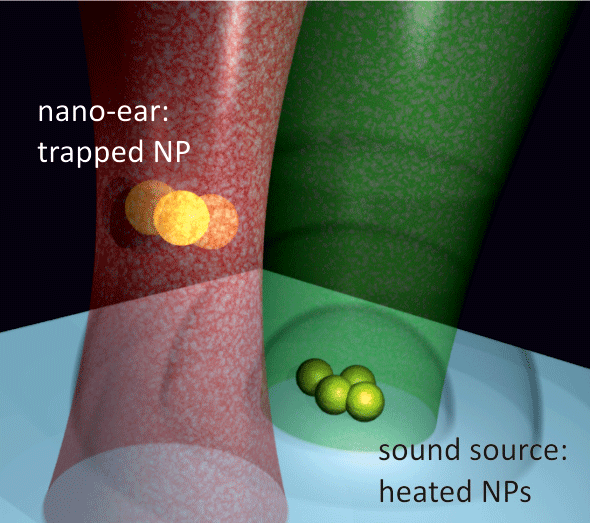

In optical traps where the laser used to trap the particle exceeds the particle’s dimensions, the particle acts like an electric dipole in the electric field. Thus acoustic vibrations can mechanically perturb dielectric particles and voltage changes can be measured by detecting the gold nanoparticle’s tiny displacement, which is typically around —roughly equivalent to a micro-electron-volt increase in the nanoparticle’s kinetic energy. Ohlinger et al.’s setup consists of two sound sources embedded in a water-based medium and an “ear”—a gold nanoparticle trapped in a laser beam. One sound source is a tungsten needle glued on a loudspeaker and immersed into a water drop. A second, more microscopic sound source is provided by an aggregate of gold nanoparticles printed on a glass substrate (Fig. 1). Ohlinger et al. use a laser to excite plasmons on the surface of these nanoparticles, which in turn heats the particles and causes them to generate acoustic waves (photoacoustic effect) at a frequency of hertz ( ).

Turning on either sound source causes the distribution of the trapped particle’s position to spread out along the same direction as the propagating sound wave—evidence that oscillating water near the nanoparticle is exerting a driving force in addition to the trapping potential. To test the ultimate sensitivity of their device, Ohlinger et al. analyze the frequency dependence of the nanoparticle’s position at the same frequency as the thermally generated sound waves emitted from the nanoparticle aggregate. When this sound source is switched on, a clearly recognizable single peak at the frequency of the sound source appears superimposed on the spectrum of Brownian motion. Ohlinger et al. estimate that their nanoacoustic device can detect vibrations at a power level as low as decibels (i.e., orders of magnitude more sensitive than the threshold for human hearing).

The concept introduced by Ohlinger et al. may open new ways for obtaining useful information on micro objects that produce acoustic vibrations. Furthermore, a new type of acoustic microscopy with an optical readout of nonequilibrium fluctuations of the particle’s environment could be built based on a set of nanoears distributed in a sample that “listens” to acoustic signals and collects amplitudes, phases, and propagation directions of acoustic waves to get an insight into the sources. Furthermore, their study suggests that optical tweezers may provide a novel way to sense energy dissipation (in the form of vibrations) or surface plasmons [10].

References

- A. Ashkin, J. M. Dziedzic, J. E. Bjorkholm, and S. Chu, Opt. Lett. 11, 288 (1986)

- C. Lapointe, T. Mason, and I. I. Smalyukh, Science 326, 1083 (2009)

- K. Schutze, H. Pösl, and G. Lahr, Cell. Mol. Biol. 44, 735 (1998)

- J. Liesener, M. Reicherter, T. Haist, and H. J. Tiziani, Opt. Commun. 185, 77

- D. G. Grier, Nature 424, 810 (2003)

- A. Ohlinger, A. Deak, A. A. Lutich, and J. Feldmann, Phys. Rev. Lett. 108, 018101 (2012)

- K. Svoboda and S. M. Block, Opt. Lett. 19, 930 (1994)

- P. M. Hansen, V. K. Bhatia, N. Harrit, and L. B. Oddershede, Nano Lett. 5, 1937 (2005)

- L. Bosanac, T. Aabo, P. M. Bendix, and L. B. Oddershede, Nano Lett. 8, 1486 (2008)

- N. J. Halas, S. Lal, W.-S. Chang, S. Link, and P. Nordlander, Chem. Rev. 111, 3913 (2011)