High-Precision Measurements Using Lots of Cold Atoms

A research team in Germany has used about ultracold atoms in an array of traps to demonstrate a sensitive detector that exploits the atoms’ quantum properties. The team measured a magnetic field with high precision, but the same technique could lead to precise tests of general relativity or to improved accuracy of atomic clocks.

Atom interferometry allows sensitive measurements of anything that can perturb the quantum waves of atoms, such as gravitational or magnetic fields. The technique can be particularly precise if the atoms are placed in a so-called Bose-Einstein condensate (BEC), an ultracold state in which they are all in the same quantum state and act like a single quantum entity.

For example, to measure a magnetic field with high precision, researchers can place a BEC in the field and determine the frequency of microwave radiation needed to drive a specific atomic transition between two magnetically sensitive states. To improve the precision in such experiments, it helps to measure as many atoms as possible, to increase the amount of averaging and reduce the uncertainty. But increasing the number of atoms is tricky. If you try to pack more atoms into a BEC of a fixed volume, the higher density causes some of them to pair up into molecules, precipitating them from the BEC. If you make the trap bigger to keep the density constant, it becomes harder to keep the BEC under control.

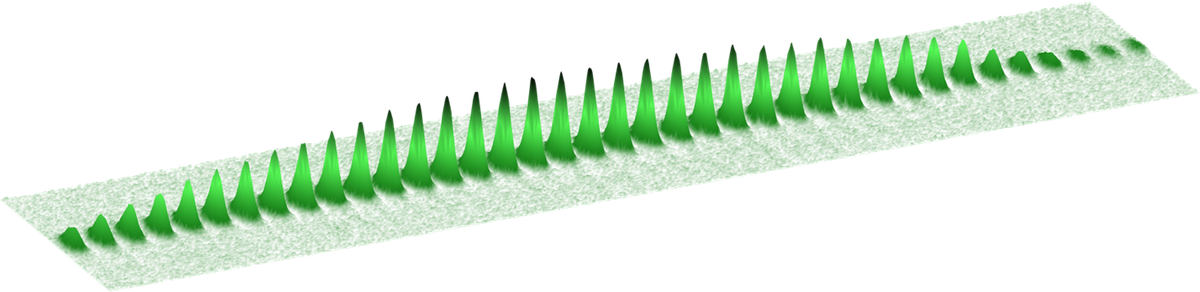

Markus Oberthaler and co-workers at the University of Heidelberg in Germany have now found a way to overcome this problem. Instead of making one big BEC, they have made many small ones, held in an optical trap in which the interference of laser beams creates a kind of one-dimensional corrugated array of trapping sites micrometers apart. Each BEC is independent of the others, but they can all be measured at the same time. The team has made up to BECs, each comprising – atoms of rubidium- cooled to around nanokelvin.

Having more atoms reduces the statistical uncertainty, but the team further improved their measurement precision with a technique called spin squeezing, which has previously been used with individual BEC’s [1,2]. Squeezing means reducing the quantum uncertainty in one variable, such as position, in exchange for increasing it in another, such as momentum. The uncertainty principle requires only that the product of the two remain above a minimum value.

The variable that Oberthaler and his colleagues squeezed was related to the difference in the atomic populations of two specific quantum states, denoted and . They used precisely timed trains of microwave pulses to manipulate the quantum states of the BECs and generate the squeezing. The team then transformed the BECs in order to put those in state into a magnetically sensitive state . This switching enabled the team to make a very precise measurement of a magnetic field by looking at how the field perturbed the energy separation between and .

The researchers found their system had a sensitivity as small as 310 picotesla for magnetic field measurements, and they also detected magnetic field gradients of just picotesla per micrometer. “Our magnetometer combines good magnetic field sensitivity with high spatial resolution,” says Heidelberg team member Wolfgang Muessel. “This makes it an ideal system for magnetic field microscopy, which is used for solid-state surface characterization.” He says that since atomic states can also be sensitive to motion, the technique could enable precision tests of general relativity or the detection of gravitational waves.

“This very challenging experiment is beautifully conducted and analyzed,” says Max Riedel, a consultant at Siemens in Munich. “A system like this would be suitable to measure a wide variety of gradients, from magnetic DC fields to radiofrequency or microwave gradients.” Because of the precision introduced by the measurement of many atoms simultaneously, he adds, “the system could in principle also compete with atomic clocks.” Robert Sewell of the Institute of Photonic Sciences in Barcelona, Spain, says that the new work “takes a significant step towards practical applications of these techniques.”

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Philip Ball

Philip Ball is a freelance science writer in London. His latest book is How Life Works (Picador, 2024).

References

- C. Gross, T. Zibold, E. Nicklas, J. Estève, and M. K. Oberthaler, “Nonlinear Atom Interferometer Surpasses Classical Precision Limit,” Nature 464, 1165 (2010)

- M. F. Riedel, P. Böhi, Y. Li, T. W. Hänsch, A. Sinatra, and P. Treutlein, “Atom-Chip-Based Generation of Entanglement for Quantum Metrology,” Nature 464, 1170 (2010)