The Hole Crystal

Ordinarily, a crystal is a regular array of particles, such as atoms. But now a team of researchers has described the opposite–a crystal made entirely of holes immersed in a sea of particles. In the 2 December PRL they report computer simulations showing that, under the right conditions, the holes within a semiconductor’s electron “sea” can crystallize. They suggest how such crystals could be coaxed to form and note that similar crystals might occur naturally within stars and other astronomical objects.

Metals and semiconductors are essentially crystals of positively-charged ions arrayed in a sea of negatively-charged electrons. The electron sea surrounding the ions is complex, with several energy levels, or bands. An electron that jumps up from a lower level to a higher one leaves behind a “hole”.

Even though a hole is just the absence of an electron, it can act a lot like a particle. Holes are positively charged, and they have an apparent, or “effective,” mass–just as electrons do–that reflects their ability to move through a given material. A hole could be effectively “heavy” if collisions with atoms in the material cause it to respond sluggishly to an external electric field. Because holes can act like particles, condensed matter physicists have hypothesized for decades that they might be able to form crystals. Now Michael Bonitz of the Christian Albrechts University in Kiel, Germany, and his colleagues, have come up with the conditions such a “hole crystal” would require.

The researchers calculated that a hole crystal could form spontaneously in a semi-conductor if three requirements are met: The material has to be cold enough to slow the holes, but not the electrons–perhaps tens of degrees Kelvin–and the holes have to be both numerous and heavy. To help them stay put in a crystal, the team calculates the holes must be at least 80 times heavier than the electrons.

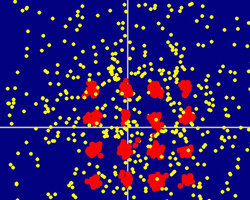

The team envisions an experiment in which a laser zaps the semiconductor, causing a bunch of electrons to hop up to a higher energy band and leave holes behind. If there are enough holes, and the semiconductor is cold enough, the slow, heavy holes should settle into a lattice that lasts until the electrons fall back to their original energies in a few microseconds. Very few semiconductors provide a hole to electron mass ratio of 80 to 1, but Bonitz and his colleagues claim it could be done with the right mix of elements. In fact, a few experimentalists have already started trying, Bonitz says.

Hugh DeWitt of Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory in California says that hole crystals and related phenomena occur in the super dense cores of white dwarfs and neutron stars. “We’re at the point where we need to do serious quantum mechanical simulations of the interiors of stars,” and the models done by Bonitz’s group are very good examples of that, he says. Bonitz points out that hole crystals are not just strange curiosities–most matter in the universe is made up of positively and negatively charged particles like holes and electrons in extreme conditions that might be right for crystals. The hole crystal may be more common than we think.

–Kim Krieger

Kim Krieger is a freelance science writer in Norwalk, Connecticut.