Liquid Helium Mimics a Superconductor

Superfluid helium flows without viscosity, just as superconductors conduct electricity without resistance, and both are explained by similar quantum mechanical theories. Although physicists have understood the deep analogies between the two systems for a long time, last year a team first demonstrated the Josephson effect–one of the most striking phenomena from superconductivity–in superfluid helium. SQUID’s, the basis for the most sensitive motion detectors, make use of the Josephson effect. In the 10 August PRL the discoverers of the superfluid effect demonstrate an important step in the development of superfluid SQUID’s and possibly other sensitive detectors: They show that simply measuring the net fluid flow through a set of small holes at various pressures gives the resonance frequencies of the fluid chamber.

Experiments with the Josephson effect are among the few quantum mechanical systems that are accessible by classical measurements, explains J.C. Seamus Davis, of the University of California at Berkeley. “You can use ammeters and voltmeters to measure a quantum state,” he says. In the early 1960’s physicists discovered that if two superconductors are connected by a “weak link,” and a constant voltage is maintained across it, the current across the link is not constant in one direction, but oscillates back and forth sinusoidally. The frequency depends on the difference in phases of the (quantum mechanical) wave functions of superconducting electrons on each side of the link, which in turn depends on the applied voltage. The Josephson effect is exploited in the superconducting quantum Interference device (SQUID), which is the essential part of ultrasensitive commercial brain scanners, precision position sensors, and advanced magnetic field detectors.

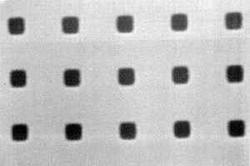

Last year Davis, his Berkeley colleague Richard Packard, and their research groups, observed the clearest example yet of the superfluid helium analog to the Josephson effect. Using the latest microfabrication methods, they made a 50-nm-thick membrane containing an array of thousands of 100-nm-diameter holes to serve as the weak link. They cooled the system to within a degree of absolute zero, and with pressure applied across the membrane (analogous to a voltage), they heard a high-pitched whistling as the helium atoms rapidly oscillated across the membrane. The demonstration suggested that a SQUID-like device based on liquid helium might be possible.

In their latest work the team focused on the net flow of helium atoms through the membrane (rather than the oscillations), analogous to the dc component of electric current. According to the Josephson effect, each value of the pressure corresponds to a specific “Josephson frequency.” They found that the net flow dramatically increased when the pressure corresponded to a Josephson frequency matching a mechanical resonance in the chamber. At those values of pressure the two synchronized vibrations–one at the membrane and the other from the chamber–combined in such a way that they produced the increased flow.

The analogous superconductivity effect was observed long ago, but this experiment shows that a critical part of the helium SQUID is workable: The amount of fluid flow at the resonant frequencies can be measured very precisely and gives information on important parameters of the system, based on simple equations. The team verified the accuracy of these relationships. The authors also speculate that such a system could be used as a detector of very small vibrations because they would have the same strong influence on the net helium flow.

“This is great stuff,” says Eric Cornell, of the University of Colorado at Boulder. He finds it “amazing” that these macroscopic quantum mechanical effects can be observed in a liquid. He is also impressed with the general result showing such a deep consistency between systems as seemingly disparate as electrons in a solid and atoms in a liquid. He adds that the Berkeley group has shown their technical prowess by going beyond the original “whistling” experiment, which itself was extremely difficult.