A breakthrough observation for neutron dripline physics

The neutron halo is one of the most spectacular phenomena that nuclear structure physicists have observed in their exploration of the isotopes at and close to the neutron dripline (the curve on a plot of atomic number versus neutron number beyond which neutron-rich nuclei begin “leaking” neutrons) using exotic beam facilities. Atomic nuclei are usually uniformly dense objects with surfaces that are nearly well defined, having only a modest amount of diffuseness. However, in halo nuclei one or more nucleons have wave functions that extend far outside the nucleus so that the matter distribution has a long tail.

The first halo nucleus observed was [1], which has two correlated neutrons in its halo [2]. The experiment that resulted in the observation of the halo was performed at Lawrence Berkeley Laboratory with the Bevalac, the only relativistic heavy-ion accelerator in the world in the mid 1980s. Researchers slammed a high-energy beam of the stable isotope into a “production target,” and then separated the short-lived products of that “fragmentation” reaction using magnets mounted on the beam line. The resulting short-lived (half-life ) nuclei were then steered onto targets of beryllium, carbon, and aluminum and the cross-sections for these resulting reactions measured.

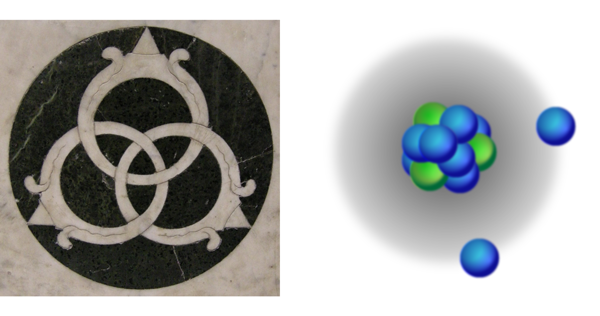

The radius of a nucleus as a function of atomic mass number can typically be calculated as ( , which for would give . The initial analysis of the data of Tanihata et al. gave a large rms matter radius of , but refinements to the reaction model eventually resulted in a conclusion that the rms radius is even larger ( [3]). Weak binding is critical to the formation of a halo, and with a two-neutron separation energy of , provided the prototypical example of this as well. Finally, essentially consists of three pieces—two neutrons and a “core”—that all must be present for the system to be bound since is unbound. Such a three-body quantum system where all three parts must be present for the existence of the system is called “Borromean” after the three interlocking rings on the th century coat of arms of the Borromeo family in northern Italy (Fig. 1). The three rings are connected in such a way that the cutting of one ring results in the separation of all three.

With advances in the production of exotic beams that have involved both improvements in the accelerators for the “primary” stable beams and the development of highly sophisticated magnetic spectrometers to separate the exotic products of the fragmentation reactions between the stable beams and the production targets, detailed studies of dripline isotopes of heavier elements have become possible. As K. Tanaka and colleagues from several institutions in Japan now report in Physical Review Letters, the Radioactive Isotope Beam Factory at RIKEN [4], which delivered its first beam in 2006, has now been used to measure a two-neutron halo in the dripline nucleus [5].

The sensitivity of the measurement is impressive, having been performed with a beam rate of only ten nuclei per hour. With twice as many protons and neutrons as , is the heaviest Borromean nucleus yet observed. The rms matter radius of deduced for differs markedly from the “standard” nuclear radius of ( . Furthermore, the cross section for the breaks sharply from the trend exhibited by the measurements of lighter carbon isotopes that Tanaka et al. also performed.

As is loosely bound, so is (although further mass measurements on this nucleus are certainly called for—Tanaka et al. quote a value of ). The authors also argue, on the basis of the systematic behavior of interaction cross sections for the heavy carbon isotopes, that the two halo neutrons preferentially occupy the orbit in the shell. This is in some contrast to the situation in , where the contribution to the ground-state wave function of the halo neutrons is divided approximately equally between the and shell model configurations [6].

In the case of , the large role played by the neutron orbit signals the disappearance of the major shell closure that exists in stable nuclei. The shifting of shell closures near the neutron dripline is a major theme of studies of exotic nuclei, with such shifts occurring systematically in neutron-rich isotopes (for example, see Refs. [7,8]). Such shifts also play an important role in the formation of the neutron halo in : The presence of an shell closure in neutron-rich isotopes, recently highlighted by the determination of the doubly-closed-shell nature of the neighboring isotone [9,10], drives the purity of the ground-state wave function of the neutron halo in .

In fact, a comparison of the three dripline nuclei— , and —provides a beautiful illustration of the core dynamic of nuclear structure physics: the sensitive dependence of nuclear behavior on proton and neutron numbers. Despite the presence of the shell closure in all three of these isotones, their geometries are quite different. is weakly bound and, as Tanaka et al. have shown, possesses a clear neutron halo (rms radius of ). and are much more tightly bound—the single neutron separation energies in both and are several —and Ozawa et al. [11] showed that their matter radii are much closer to the “normal” nuclear values of ( (the radii reported in Ref. [11] are and for and , respectively, while the corresponding values of ( are and ). In fact, while has now been shown to be one of the most exotic of the known isotopes, the neighboring isotone has proven to display, in many respects, the behavior of a conventional doubly-magic nucleus [9,10] (even if the shell closure is exotic).

In this context, it is worth noting that at only one proton above , the neutron dripline jumps from to (the heaviest bound fluorine isotope is [12]). This phenomenon continues to challenge our understanding of nuclear behavior in extreme conditions. In short, the discovery of a neutron halo in by Tanaka et al. [5] is not just a tour de force of the application of frontier experimental techniques to the search for exotic nuclear behavior. When taken together with the recent advances in the understanding of the neighboring isotone , the measurement provides a critical step forward. Detailed studies of heavier isotopes along the neutron dripline will become possible during the next decade as new exotic beam facilities and more sensitive detectors come online. These studies will reveal new halo nuclei, novel shell effects, and perhaps even phenomena that are completely unexpected in our understanding of the basic physics of the neutron dripline.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Science Foundation and the State of Florida.

References

- I. Tanihata, H. Hamagaki, O. Hashimoto, Y. Shida, N. Yoshikawa, K. Sugimoto, O. Yamakawa, T. Kobayashi, and N. Takahashi, Phys. Rev. Lett. 55, 2676 (1985)

- P. G. Hansen and B. Jonson, Europhys. Lett. 4, 409 (1987)

- J. S. Al-Khalili and J. A. Tostevin, Phys. Rev. Lett. 76, 3903 (1996)

- T. Motobayashi and Y. Yano, Nuclear Physics News 17, Issue 4, 5(2007)

- K. Tanaka et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 104, 062701 (2010)

- H. Simon et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 83, 496 (1999)

- J. Fridmann et al., Nature (London) 435, 922 (2005)

- B. Bastin et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 022503 (2007)

- C. R. Hoffman et al., Phys. Lett. B 672, 17 (2009)

- R. Kanungo et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 102, 152501 (2009)

- A. Ozawa et al., Nucl. Phys. A 691, 599 (2001)

- H. Sakurai et al., Phys. Lett. B 448, 180 (1999)

- Photograph by Sailko, http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tempietto,_formelle_18_impresa_personale_di_lorenzo_de%27_medici.JPG; See also http://www.liv.ac.uk/~spmr02/rings/medici.html