Fluctuation diamagnetism in high-temperature superconductors

More than two decades after the discovery of the cuprate high-temperature superconductors, there is still healthy debate concerning the character of the highly anomalous “normal” state above the superconducting transition temperature Tc. An unresolved issue is the extent of the temperature and magnetic-field regime in which superconducting fluctuations persist, and how best to characterize this regime theoretically. One reason for this lack of clarity is that other types of order parameter fluctuations are also significant, making disentangling the contributions from the different kinds of fluctuations highly complex.

STM and ARPES measurements show evidence of incipient order above Tc, and of a single-particle gap that persists into the normal state. However, distinguishing a superconducting gap from a density-wave gap is a subtle task. An extremely revealing set of measurements has also been carried out [1,2] on the Nernst effect, a thermoelectric phenomenon in which a voltage transverse to a temperature gradient is created in a conducting sample subjected to a magnetic field. The Nernst effect, however, is highly sensitive not only to superconducting fluctuations, but also to any type of order that leads to a reconstruction of the Fermi surface. A priori, the ideal method to detect short-range superconducting order would be to measure the magnetization. The diamagnetic response of an ordered superconductor is many orders of magnitude stronger than that of any other known state of matter, meaning that even when the superconducting correlation length is finite, the fluctuation diamagnetism can be large compared to the “background.” Moreover, magnetization is a thermodynamic quantity, and as such is not subject to the uncertainties in interpretation that arise concerning dynamical and/or nonequilibrium properties.

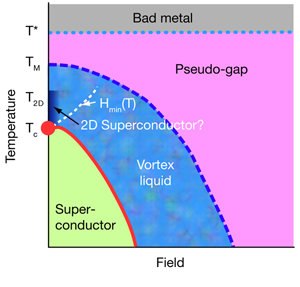

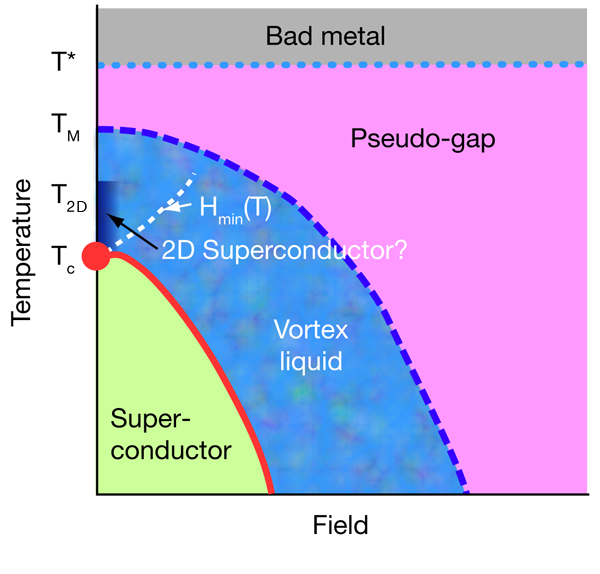

In a paper by Lu Li and co-workers appearing in Physical Review B [3], the group of N. Phuan Ong in Princeton, US, together with collaborators at Tsinghua University, China, Central Research Institute of Electric Power Industry and Osaka University, both in Japan, and Brookhaven National Laboratory, US, have compiled the results of a major experimental study of the magnetization of several important families of cuprate high-temperature superconductors over a broad range of temperatures and magnetic fields. From these, they infer a field-dependent onset temperature, TM, below which superconducting fluctuations are strong, as shown qualitatively in Fig.1. It is refreshing to find important results presented in a comprehensive and scholarly paper of adequate length. In particular, this paper takes care to justify the analysis of the raw data that is performed prior to its being interpreted.

The magnetization is measured using torque magnetometry, a technique that has the added benefit that there is essentially no spin contribution to the measured magnetization [4]. Li et al. observe a weakly-temperature-dependent paramagnetic signal at high temperatures ( T>TM), which they attribute to van Vleck paramagnetism, unrelated to superconducting fluctuations. Specifically, for T>TM, the magnetization is linear in H over the entire accessible range, and can be well fit by the expression M=(A+BT)H, with A>>BT. Li et al. assume that this contribution is present, more or less unchanged, over the entire range of T and H, and thus in their analysis they plot a “diamagnetic contribution” to the magnetization:

where Mexp is the measured magnetization. This subtraction is the only way in which the raw data is modified. None of the strong nonlinear T or H dependences observed by Li et al. can be artifacts of this subtraction. Although in much of the phase diagram the subtracted term is small compared to Mexp, close to T=TM, where the diamagnetic fluctuations are becoming undetectably small, the subtraction has a large effect on the analysis. However, other than small uncertainties in the precise value of TM, it seems unlikely that the subtraction could produce misleading results.

The boundary between the superconducting and normal states (the solid red line in Fig.1) marks a thermodynamic phase transition and is unambiguous in that the resistance is zero in the superconducting state and nonzero beyond it. The remaining lines in the phase diagram are, to the best of our current knowledge, crossovers from one state to another and hence less sharply defined. The region labeled “vortex liquid” is identified as a region of strong superconducting fluctuations because of several characteristic features of the magnetization curves: the magnetization is opposite in direction to H (diamagnetic), it is large compared to (for example) the Landau diamagnetism in conventional metals, and it is a nonlinear function of H. TM is thus identified as the point at which Md vanishes, and where Mexp changes from being a linear function of H (for T>TM) to nonlinear (for T<TM).

The nonlinearity is an expected feature of superconducting fluctuations. For small H, one expects M to grow linearly Md=-χflucH, where χfluc is the diamagnetic susceptibility. However, for H in excess of a characteristic field (that one might think of as being the mean-field Hc2), the magnetization should tend to zero. This leads one to expect that for temperatures between TM and Tc, M should exhibit a minimum as a function of applied field at a nonzero, Hmin. The fact that such behavior is observed in the “vortex liquid” region above Tc is the strongest piece of evidence for a superconducting origin of the observed effects. The authors observed that in all the materials studied here, other than optimally doped YBa2Cu3O7, Hmin→0 as T→Tc, but Hmin grows increasingly large with increasing T above Tc, as shown schematically by the green dashed line in Fig.1. The large magnitude of Hmin at elevated temperatures implies that high applied fields (up to 45 T in the present paper) are needed to observe this field dependence clearly. Indeed, because the mean-field Hc2 in the high-temperature superconductors is so large, in most cases even experiments carried out up to 45 T only access fields somewhat in excess of Hmin. The values of Hc2 at most temperatures less than TM are higher than have been achieved, so the high field portions of the schematic phase diagram in Fig.1 must be obtained by extrapolation.

Li et al. present another argument to confirm the superconducting origin of the observed diamagnetism. There is general consensus that the resistive transition at temperatures T<Tc marks the boundary between a superconducting phase and a vortex liquid. The vortex liquid is characterized by strong, local, superconducting correlations and a well-defined short-distance superfluid stiffness that is degraded, at long distances, by vortex motion. It is therefore significant that the thermal evolution of the magnetization at moderate fields in the range Hmin<H<Hc2, is smooth through Tc, and only shows a qualitative change as T approaches TM. Taken together, these various observations constitute extremely compelling evidence of a broad range of superconducting fluctuations above Tc as a generic feature of the phase diagram of the cuprate high-temperature superconductors.

Two dramatic features of the data do not follow straightforwardly from simple considerations of superconducting fluctuations.

(1) At least in two families of cuprates, Bi2Sr2CaCu2O8+x and Bi2Sr2-yLayCuO6, the low field magnetization exhibits apparently nonanalytic behavior, in that M∼|H|x with x<1 as H→0, for a range of temperature T2D>T>Tc (shown as the shaded bar in Fig.1). If this behavior truly extends to arbitrarily small H, it implies a divergent susceptibility, which in turn suggests that T2D is a critical point, suggesting a new, distinct, critical phase of matter, the onset of which occurs below this temperature. An idea of what such a phase might look like was proposed by Oganesyan et al. [5]. They observed that in a layered superconductor with zero Josephson coupling between planes, the critical phase below the Kosterlitz-Thouless transition temperature of the individual layers has a diamagnetic magnetization at small H given by the scaling relation

While this is not quite of the same form as reported by Li et al. and in an earlier study by Wang et al. [6], it resembles the data at least to the extent that it produces a divergent susceptibility for a range of temperatures. An apparent problem with this interpretation is that even weak but finite interplane Josephson coupling inevitably leads to a 3D superconducting transition with Tc>T2D. (A different interpretation of the vortex liquid as an “incompressible superfluid” was proposed by Anderson [7].)

(2) It is not obvious why Hmin should tend to vanish as T→Tc. Given that it does, simple scaling arguments imply that near Tc, the characteristic field strength Hmin∼ϕo/ξ2 with ϕ0=hc|2e.

It is not possible to extract accurate critical exponents from the published data; the existing data is consistent with the scaling behavior Hmin∼(T-Tc)2ν, with 2ν∼1. This is reasonable for a 3D classical critical point, or even a 2D Ising transition, but not remotely consistent with 3D XY (Kosterliz-Thouless) scaling. Given the small magnitude of the interplane couplings in these materials, it would be surprising to find 3D critical scaling over a broad range of temperatures above Tc.

What are the implications of these two observations? To begin with, it is worth noting that a phase diagram with a similar topology to that shown in Fig. 1 was recently inferred [8] from transport and other measurements on the stripe-ordered high-temperature superconductor La2-xBaxCuO4, with x=1/8. Here, an order of magnitude drop in the inplane resistivity marks the transition into some form of vortex liquid, while the interplane resistivity continues to grow with decreasing temperature. While a relatively weak diamagnetic signal persists to a higher temperature TM (similar to what is observed in La2-xSrxCuO4, with x∼1/8), in the present case, a sharp increase in the diamagnetic contribution to the susceptibility occurs at the same temperature, T′M, as the resistive anomaly. ( T′M is also the point at which spin-stripe ordering occurs, as determined by neutron scattering.) T2D appears dramatically in this material as the point at which the in-plane resistivity becomes immeasurably small, although the interplane resistivity remains large, so that for a range of temperatures below T2D, this material appears to be literally a 2D superconductor. Finally, Tc is the point at which flux expulsion, in the sense of perfect diamagnetism, first appears. (There is an intermediate temperature, T2D>T3D>Tc , below which the interplane resistivity becomes immeasurably small.)

In the case of the superconductor La2-xBaxCuO4, we have presented a plausible theoretical scenario in which the existence of a spatially modulated superconducting phase, which we called a pair-density-wave (PDW), produces the observed anomalies [9,10]. Because the PDW order oscillates in sign, in many geometries [10] the interplane Josephson coupling can cancel exactly, producing an emergent layer decoupling and a delicate, 2D superconducting state. Moreover, in contrast to a usual superconductor, the long-range phase coherence of this phase is, generically, disrupted by even very weak disorder, possibly leading to a superconducting glass phase. Only when a usual, uniform, component of the superconducting order parameter develops can 3D correlations begin to grow, leading to a superconducting phase with true long-range order. While there are many aspects of the data that warrant further study, it seems to us likely that the same circle of ideas can account for the anomalous magnetization data in the bismuth-based high-temperature superconductors.

The observation of a clear thermodynamic signature of local superconducting order in a substantial portion of the pseudogap regime is an important step forward for the field. However, the pseudogap is often observed to onset at a significantly higher temperature, T*>TM, as shown schematically in Fig. 1. It it is also clear, from a variety of experiments, that other types of ordered states contribute significantly to the changes that occur at T∼T*. For instance, the recent studies of Daou et al. [2] reveal the growth of a large, anisotropic component of the Nernst effect below T* that continues to grow through TM, suggestive of an intrinsic electronic tendency to spontaneous breaking of the point-group symmetry—electron nematic order [11]. Sorting out the relations between the different types of order and order-parameter fluctuations remains a key open problem.

References

- Y. Wang et al., Phys. Rev. B 64, 224519 (2001)

- R. Daou et al., Nature 463, 519 (2010)

- L. Li, Y. Wang, S. Komiya, S. Ono, Y. Ando, G. D. Gu, and N. P. Ong, Phys. Rev. B 81, 054510 (2010)

- The spin contribution to the magnetization is small at these elevated temperatures in any case. Moreover, since spin-orbit coupling is weak, the spin magnetization is approximately parallel to the applied magnetic field, whereas the torque is proportional to the component of the magnetization perpendicular to the magnetic field

- V. Oganesyan et al., Phys. Rev B. 73, 94503 (2006)

- Lu Li et al., Europhys. Lett. 72, 451 (2005)

- P. W. Anderson, Phys. Rev. Lett. 100, 215301 (2008)

- Q. Li et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 98, 247003 (2007); J. M. Tranquada et al., Phys. Rev. B 78, 174529 (2008)

- E. Berg et al., Phys. Rev. Lett. 99, 127003 (2007)

- E. Berg et al., New J. Phys. 11, 115004 (2009)

- For a review, see E. Fradkin et al., arXiv:0910.4166