Negative Ions in Cold Storage

Negative ions (anions) play an important role in chemical reactions in interstellar space and planetary atmospheres. Molecular anions were, for example, observed in the ionosphere of Saturn’s moon Titan, and their collisions with neutral atoms and molecules are thought to affect the production of unsaturated carbon and nitrogen chain molecules in the interstellar medium [1]. Laboratory experiments with anions are, however, difficult, as the ions are easily disturbed by background radiation or collisions with other particles. These effects can be mitigated in ion traps that have radiation shielding and extremely low pressures. But ion trapping is limited to experiments with ions at rest, while many anion interactions of interest are better studied when the ions move at high speeds. Using a new cryogenic ion-storage ring, Erik Bäckström and colleagues at Stockholm University, Sweden, have successfully stored a -kilo-electron-volt (keV) beam of negative sulfur ions ( ) for, on average, seconds (s). The long storage time allowed them to measure a natural decay time of s for the only excited bound state of the ion [2], the longest lifetime measurement of a negative ion in a stored beam. The new storage machine, and similar facilities planned around the world, will allow scientists to study negative ions with lifetimes of minutes or hours—such as the atomic and molecular ions found in planetary ionospheres and astrophysical environments.

The formation of an anion (binding of an electron to a neutral atom) and a cation (removal of an electron) involve different forces. To form an anion, a neutral atom binds an excess electron because the “intruder” electron polarizes the atom’s electronic shell. This distortion generates a dipolar electric field that, in turn, attracts the electron. In general, the stability of a negative ion depends on the electron cloud’s charge distribution and, in particular, on electron–electron correlation effects. These interactions are small compared to the direct electrostatic forces in most neutral atoms and positive ions (cations). But they often dominate in negative ions. Because of this sensitivity, negative ions, and specifically the lifetimes of their excited states, are excellent tests of the theory of quantum-mechanical, many-body motion in atomic electron shells [3].

Measuring these excited states is, however, an experimental challenge. In anions, the long-range attractive potential acting on an excited electron isn’t Coulomb-like, and, as a result, these ions have a much smaller number of bound excited electronic quantum states than neutral atoms or cations. And, with few exceptions, symmetry laws suppress the emission of light as the anion transitions between states, ruling out the use of conventional spectroscopy. In addition, the ions have to be in an extremely low-pressure environment to minimize collisions with other particles. Even at millibars, experiments have only been able to store negative ions for tens of seconds [4], limiting studies to the excited states of heavier ions like selenium and tellurium, which have relatively short lifetimes. Lighter and more abundant elements, such as sulfur and oxygen, have anionic excited states that are expected to live much longer, with predicted for the excited state and up to hours for that in [4].

In their experiments, Bäckström et al. measured the lifetime of negative sulfur ions using the method of laser photo detachment [3]. This technique detects the neutral atom left when the anion absorbs a photon and emits an electron. The minimum (threshold) photon energy needed to detach the electron from the anion in its ground state is the binding energy. Smaller photon energies are sufficient for detachment when the anion is in an excited state. Hence, the lifetime of an excited state can be deduced by observing the subthreshold photodetachment signal as a function of time. Photodetachment events from a fast beam of negative ions generate fast neutral atoms, which can be easily separated from the remaining ions and detected one by one.

The remaining challenge is finding a way to store the ions for long enough to measure their lifetimes. Magnetic storage rings—essentially smaller versions of synchrotrons—can, for example, be used for atomic and molecular physics [5] and allow storage times of tens of seconds for most low-ionization state ions. Similar ion-beam storage devices can be built using electrostatic instead of magnetic deflecting fields [6], and this is the approach Bäckström et al. follow. Electrostatic rings are more limited in beam energy. But they are also more compact than magnetic ones and can handle a wider mass range of ions, including heavy atoms and molecules.

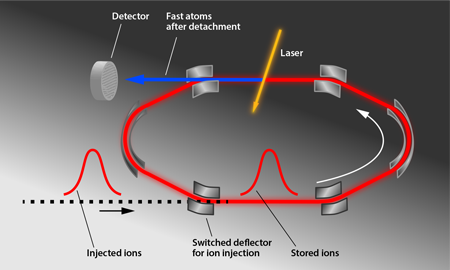

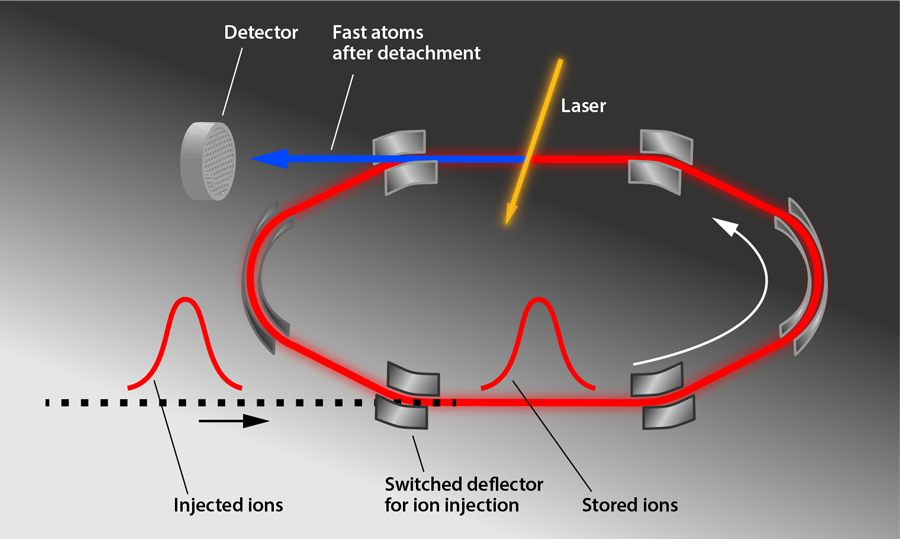

Figure 1 shows the storage ring (DESIREE for “Double Electrostatic Ion Ring Experiment”) used in the experiments by Bäckström et al. The storage ring itself is meters in diameter and is enclosed in a separate vacuum container that is cooled to —the essential step to achieving a long storage time. This container is housed in a cryostat that is surrounded by an insulating vacuum and radiation shields. A -keV pulse of ions, which were produced by sputtering an target with ionized cesium atoms, was injected into the ring, and electrostatic deflectors were switched on to keep the ions circulating in a closed orbit. The cold, shielded environment allows the researchers to reach a pressure on the order of millibars and to minimize blackbody radiation, thus limiting particle collisions and unwanted photon absorption. A laser intersects the ions’ path and induces photodetachment, producing neutral atoms that are counted by an ion detector for up to an hour. The researchers analyzed the decrease of the subthreshold photodetachment signal to determine the ions’ excited-state lifetime ( ), a value slightly longer than predicted ( ) [4]. In comparison, the heavier anions selenium and tellurium had measured lifetimes that were shorter than predicted [2,4]. Taken together, the experiments hint that predictions of anion energy levels may need to be revised.

The DESIREE storage ring is one of several existing or planned experiments that are allowing scientists to explore ion collisions at low temperatures, like those that form complex molecules in the interstellar medium, where temperatures can approach [1]. One group designed a cryogenic ion-beam trap at and, in 2011, was able to store sulfur hexafluoride negative ions ( ) for, on average, [7]. Two cryogenic electrostatic ion storage rings similar to DESIREE [2] are RICE [8] in Tokyo and CSR [9] in Heidelberg. These devices, which are starting operation, will allow scientists to study molecular negative ions [6,7], and in particular, the influence of the ion’s vibrational and rotational states on electron detachment. Because blackbody radiation is essentially absent in these new cryogenically cooled ion-beam storage devices, scientists have new opportunities to perform controlled, laboratory experiments with those anions and cations [10] that influence interstellar chemistry. And measurements of hour-scale lifetimes, such as the ones obtained in traps for ions at rest, are becoming a reality for stored ion beams.

References

- M. Larsson, W. D. Geppert, and G. Nyman, “Ion Chemistry in Space,” Rep. Prog. Phys. 75, 066901 (2012)

- E. Bäckström et al., “Storing keV Negative Ions for an Hour: The Lifetime of the Metastable level in S,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 114, 143003 (2015)

- T. Andersen, “Atomic Negative Ions: Structure, Dynamics and Collisions,” Phys. Rep. 394, 157 (2004)

- P. Andersson et al., “Radiative Lifetimes of Metastable States of Negative Ions,” Phys. Rev. A 73, 032705 (2006)

- A. Wolf, “Heavy ion storage rings,” in Atomic Physics with Heavy Ions, edited by H. F. Beyer and V. P. Shevelko (Springer, Berlin, 1999)[Amazon][WorldCat]

- L. H. Andersen, O. Heber, and D. Zajfman, “Physics with Electrostatic Rings and Traps,” J. Phys. B 37, R57 (2004)

- S. Menk, S. Das, K. Blaum, M. W. Froese, M. Lange, M. Mukherjee, R. Repnow, D. Schwalm, R. von Hahn, and A. Wolf, “Vibrational Autodetachment of Sulfur Hexafluoride Anions at its Long-Lifetime Limit,” Phys. Rev. A 89, 022502 (2014)

- Y Nakano, W Morimoto, T Majima, J Matsumoto, H Tanuma, H Shiromaru, and T Azuma, “A Cryogenic Electrostatic Storage Ring Project at RIKEN,” J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 388, 142027 (2012); and http://www.riken.jp/amo/research/RICE.html

- R. von Hahn et al., “The Electrostatic Cryogenic Storage Ring CSR–Mechanical Concept and Realization,” Nucl. Instrum. Methods B 269, 2871 (2011); and http://www.mpi-hd.mpg.de/blaum/storage-rings/csr/

- C. Krantz et al., “The Cryogenic Storage Ring and its Application to Molecular Ion Recombination Physics,” J. Phys.: Conf. Ser. 300, 012010 (2011)