When One Plus One is More than Two

Sixty years ago, scientists discovered that they could stack ordinary doped semiconductors together to make diodes and transistors. The heart of such devices is an interface whose electronic transport properties are unlike either material from which it formed. Today researchers are applying the same strategy to build “functional interfaces” with perovskite oxides, materials in which the structural, magnetic, and electronic properties are strongly coupled. The properties of an interface between two perovskites are rarely a simple mixture of the parent materials [1]. For example, the interface between two insulating perovskites can be conducting [2]. Now, based on simulations, a team led by Xifan Wu at Temple University in Pennsylvania has made the similarly surprising finding that the interface between two model perovskites, calcium titanate and barium titanate, has a structure whose spontaneous electric polarization is greater than that of either material in its bulk form [3]. Materials with a spontaneous electric polarization are known as ferroelectrics, and because their polarity can be switched with an applied electric field, they can be used to store bits of information. The researchers’ approach for enhancing electric polarization should apply to many perovskites and has the potential to greatly expand the number of available ferroelectric materials.

Perovskite oxides have a generic formula ABO3, where A is typically an alkaline-earth or rare-earth element and B is a transition metal. There are many ways to combine the A and B cations, and the properties of the resulting materials are diverse. A fraction of the electrons from the A and B cations transfer to the oxygen anions. Those electrons that remain on the B cations tend to occupy the d orbitals, which are localized. These electronic states can be spin-polarized (the root of magnetism); be strongly correlated; or produce charge and orbital ordering. Moreover, these degrees of freedom are strongly coupled, and a small change to one of them—say, from applying strain to the material [4] or changing the local chemical environment (as at an interface)—can greatly affect the others, leading to big changes in material properties [1, 5].

Roughly speaking, ABO3 compounds have a cubic crystal structure. The A and B cations are, respectively, located at the corners and centers of the cubic unit cell of the crystal lattice, and each B site is surrounded by an octahedral “cage” of oxygen atoms. However, this cubic structure is only stable for perovskites in which the ionic radii fall within a certain range. Many of the compounds are thus prone to distortions that lower their symmetry.

Wu and collaborators studied the interface between two prototypical perovskite oxides that display different degrees of distortion in their bulk forms. One is barium titanate (BaTiO3), in which the Ti atoms and O cages optimize their coordination by shifting in opposite directions. (See note in Ref. [6].) This collective motion of the atoms creates a separation between positive and negative charge and is responsible for the appearance of a ferroelectric moment (relative to a cubic structure) along the [001] axis of the crystal. The other material the authors use is calcium titanate (CaTiO3). Ca has the same valence charge as Ba, but it has a smaller ionic radius, which causes CaTiO3 to have a distorted cubic structure that is different from the one in BaTiO3. Specifically, the oxygen cages all rotate (in phase) around the [110] axis and around the [001] axis, which suppresses ferroelectricity in bulk CaTiO3[7].

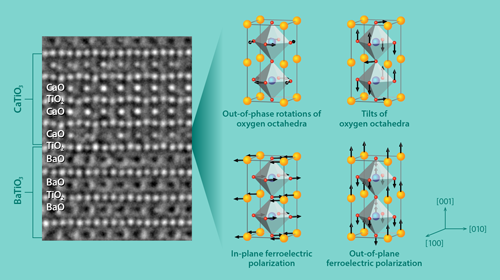

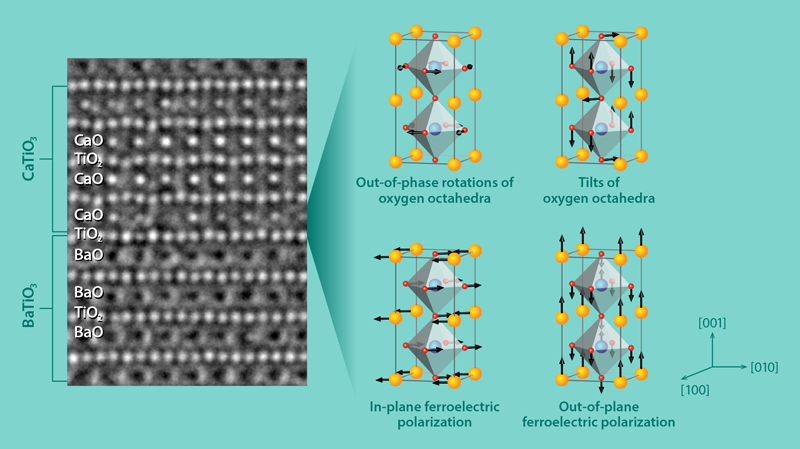

However, Wu and collaborators have found that CaTiO3 adopts the structure of a highly polarized ferroelectric, BiFeO3, when it is grown in a BaTiO3∕CaTiO3 superlattice supported by a SrTiO3 substrate. (The BiFeO3structure can form in strained CaTiO3, but it is metastable.) The researchers predicted the structural change to CaTiO3 using first-principle simulations, and they explained that it originates primarily because the oxygen cages in BaTiO3resist rotation. This suppresses the usual in-phase rotation of the oxygen cages in CaTiO3in favor of an out-of-phase rotation of the cages like that occurring in BiFeO3. Two additional effects help to enhance ferroelectricity. First, the SrTiO3 substrate strains the CaTiO3 lattice, which is known to favor the appearance of an electric polarization along the [110] axis of CaTiO3 [8]. Second, the electric polarization along the [001] axis in BaTiO3 induces a similar polarization in CaTiO3. The team demonstrated these structural changes by growing the superlattices using the technique of pulsed-laser deposition and imaging the atom positions with high-resolution transmission electron microscopy (Fig. 1, left).

The enhanced polarization is localized to the atomic layers of CaTiO3 that are closest to the BaTiO3 layer. As a result, the polarization enhancement will be strongest in a superlattice with many interfaces. The researchers also pinpointed the origin of the mechanism that stabilizes the BiFeO3-like structure. It is a (linear) coupling between four types of atom motion (Fig. 1, right): two forms of rotation of the oxygen cages and two forms of atomic shift that induce an electric polarization. When these four distortions occur together, the total energy of the superlattice decreases. This differs from the mechanism for the appearance of ferroelectricity in so-called hybrid improper ferroelectrics [9, 10], where the coupling is between three types of distortions. Also, compared to other proposals, the authors’ approach produces ferroelectrics that can be switched with a relatively small amount of energy, an advantage for making ferroelectric devices that consume little power. This is because the switching would not require the oxygen cages to rotate back and forth, which is energetically expensive.

The scheme introduced by Wu and collaborators opens a path to building artificial ferroelectrics from materials that aren’t themselves strongly ferroelectric. The requirements are simple. One of the parent compounds must have the same distorted cubic structure as bulk CaTiO3; the other parent compound must have a structure that resists the rotation of the oxygen cages, like BaTiO3. Since both kinds of materials are common, the authors’ approach should be widely applicable. In the future, researchers could explore superlattices where the CaTiO3-like layer is magnetic. In such structures, there might be an interaction between the induced ferroelectricity and magnetism that leads to “multiferroic” properties, which are potentially useful for low-power memory devices.

With today’s oxide-growth techniques, researchers can control the positions of individual atoms—a level of precision that rivals standard semiconductor technology. They have also made great progress in the theoretical modeling of ferroelectrics. As the research by Wu and colleagues shows, these advances allow theoretical predictions about complex systems to be tested in the lab. More surprises can be expected from this happy marriage of theory and experiment.

This research is published in Physical Review X.

References

- P. Zubko, S. Gariglio, M. Gabay, Ph. Ghosez, and J. -M. Triscone, “Interface Physics in Complex Oxide Heterostructures,” Annu. Rev. Condens. Matter Phys. 2, 141 (2011).

- H. Y. Hwang, Y. Iwasa, M. Kawasaki, B. Keimer, N. Nagaosa, and Y. Tokura, “Emergent Phenomena at Oxide Interfaces,” Nature Mater. 11, 103 (2012).

- H. Wang, J. Wen, D. J. Miller, Q. Zhou, M. Chen, H. N. Lee, K. M. Rabe, and X. Wu, “Stabilization of Highly Polar BiFeO3-like Structure: A New Interface Design Route for Enhanced Ferroelectricity in Artificial Perovskite Superlattices,” Phys. Rev. X 6, 011027 (2016).

- D. G. Schlom, L. -Q. Chen, C. -B. Eom, K. M. Rabe, S. K. Streiffer, and J. -M. Triscone, “Strain Tuning of Ferroelectric Thin Films,” Annu. Rev. Mater. Res. 37, 589 (2007).

- J. M. Rondinelli and N. A. Spaldin, “Structure and Properties of Functional Oxide Thin Films: Insights From Electronic-Structure Calculations,” Adv. Mater. 23, 3363 (2011).

- This structure exists at room temperature—the temperature relevant to the experiments by Wu and colleagues—or under compressive strain. Bulk BaTiO3 assumes other structures at low temperature..

- N. A. Benedek and C. J. Fennie, “Why Are There So Few Perovskite Ferroelectrics?,” J. Phys. Chem. C 117, 13339 (2013).

- C.-J. Eklund, C. J. Fennie, and K. M. Rabe, “Strain-Induced Ferroelectricity in Orthorhombic CaTiO3 from First Principles,” Phys. Rev. B 79, 220101 (2009).

- J. M. Rondinelli and C. J. Fennie, “Octahedral Rotation-Induced Ferroelectricity in Cation Ordered Perovskites,” Adv. Mater. 24, 1961 (2012).

- E. Bousquet, M. Dawber, N. Stucki, C. Lichtensteiger, P. Hermet, S. Gariglio, J. -M. Triscone, and Ph. Ghosez, “Improper Ferroelectricity in Perovskite Oxide Artificial Superlattices,” Nature 452, 732 (2008).