Probing Quarkonium Production in Jets

On November 11, 1974, two research groups, one at SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory [1] and the other at Brookhaven National Laboratory [2], announced the discovery of a new particle, a meson soon to be called the J∕𝜓. What was so surprising about the particle was that it lived about a thousand times longer than expected. Now known as the “November Revolution” of particle physics, the discovery had a huge impact on the field. Theorists jumped to interpret the result, and only 8 days after the initial announcement, a study by Thomas Appelquist and David Politzer interpreted the particle as a bound state of a charm quark and an anticharm quark [3]. Since then, much progress has been made in understanding the physics of the J∕𝜓 and other forms of quarkonium, a hadron comprised of a heavy quark (a charm or bottom quark) and its antiquark. Today, however, the theory describing how quarkonium is produced in high-energy collisions is still incomplete. Now, the Large Hadron Collider beauty (LHCb) collaboration [4] has used a new way to study the J∕𝜓, which looks at how the particle is produced within a jet—a narrow, collimated cone of hadrons created in high-energy particle collisions. The results will help researchers refine both theoretical models for quarkonium and numerical Monte Carlo methods that are crucial for the description of particle collider experiments.

Being a bound state of a quark and an antiquark, quarkonium is in some ways similar to positronium, a bound state of an electron and an antielectron (positron). Like positronium, quarkonium’s different states can be classified in terms of their spin, orbital angular momentum, and total spin. For instance, the charm-anticharm bound state with the lowest energy is the paracharmonium state (known as 𝜂c), with spin 0, and it is analogous to parapositronium, in which the electron and positron have antiparallel spins. The higher energy J∕𝜓 state, with spin 1, is instead analogous to orthopositronium, in which the electron and positron spins are parallel.

However, while positronium is bound together by electromagnetic forces, quarkonium is bound together by the strong interaction, which is described by the theory of quantum chromodynamics (QCD). Quarkonium is thus an important test bed for QCD phenomenology. From an experimental point of view, the J∕𝜓 is particularly interesting because it is easy to produce and observe at particle accelerators as a product of high-energy collisions. From a theoretical perspective, however, the mechanisms by which the J∕𝜓 and other quarkonia are produced still defy our understanding. This is because QCD calculations are only possible in a perturbative regime. But quarkonium production involves quark interactions on many energy and length scales, not all of which can be tackled perturbatively. For example, the binding of all quark states, including quarkonium, cannot be calculated analytically.

The calculations of J∕𝜓 production by Appelquist and Politzer [3] were done in the so-called color-singlet model (CSM). Such a model assumes that the heavy quark-antiquark pair is a color-singlet (a state with a total color charge of zero) and is in an angular momentum state whose quantum numbers match those observed for the J∕𝜓. However, the CSM fell out of favor in the 1990s when it failed to reproduce experiments on J∕𝜓 production at the Tevatron [5]. It appeared that new production channels were needed, which led to the adoption of an effective field theory called nonrelativistic QCD (NRQCD) [6]. In the NRQCD description, hard collisions create quark-antiquark pairs that can have any quantum numbers. The pairs then evolve into final-state particles like the J∕𝜓 with probabilities governed by certain matrix elements. These matrix elements can’t be calculated with perturbative QCD and must instead be extracted from experiments. They can then be used to make predictions in other settings.

While NRQCD has delivered successful predictions for many years, it has also led to conclusions that are in conflict with experiments. For instance, NRQCD wrongly predicted that J∕𝜓 particles emerging from a collision with large transverse momentum should be transversely polarized [7]. This is possibly the result of corrections to the calculations that turn out to be larger than expected, or because of how the matrix elements are extracted from experimental data. This extraction depends on certain theoretical assumptions that might be inaccurate. Different groups have used different assumptions, leading to significantly different matrix elements for the same processes and causing confusion in the field. The new LHCb experiments may now help researchers constrain and refine the process for NRQCD matrix-element extraction.

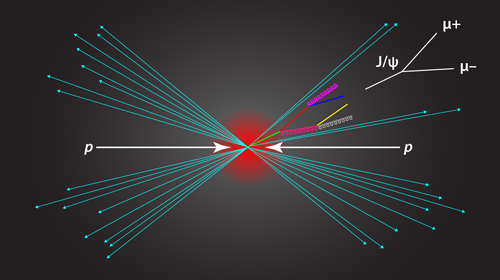

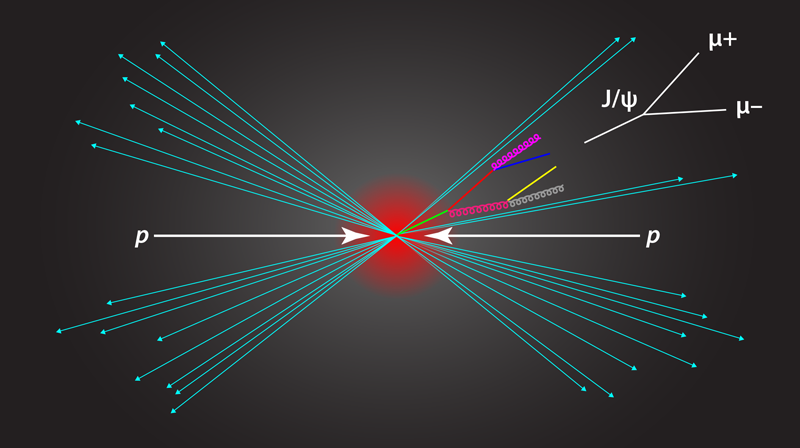

The LHCb measurement was motivated by theoretical work, carried out by us and our collaborators [8], which proposed to study the production of J∕𝜓 in jets created in high-energy particle collisions. The initial collisions produce quarks and gluons that eventually form a jet of hadrons that can include quarkonia like the J∕𝜓 (see Fig. 1). Ref. [8] indicated that the distribution of the J∕𝜓 within a jet is sensitive to the underlying production mechanisms. In particular, it showed that measurements of the ratio of the momentum carried by the J∕𝜓 to the momentum carried by the jet could be used to test the accuracy of different matrix element extractions.

The LHCb collaboration has now realized this proposal, carrying out the first experimental study of prompt quarkonium production within a jet. The success of the experiment hinged on improvements in LHCb’s data-taking scheme, which the collaboration introduced in 2015. These developments allowed the team to record many more J∕𝜓 candidate events than previous studies, including, for instance, candidates with low transverse momentum pT. Such particles are hard to detect because they are created with low energies, to which detectors are less sensitive, and at small angles with respect to the colliding proton beams, where there is a large background from other particles. LHCb determined z (the ratio of the transverse momentum carried by the J∕𝜓 to the transverse momentum carried by the whole jet) both for the J∕𝜓 that are produced promptly and those that are produced subsequently from the decay of other particles ( b hadrons) in the jet. The ability to measure the J∕𝜓 down to very low pT allowed LHCb to measure the entire z distribution.

One of the most important conclusions of this work is that PYTHIA [9]—a Monte-Carlo-based simulation program widely used to model particle collisions at high energy—does a poor job at reproducing the z distribution for prompt J∕𝜓 production. Experimentalists use PYTHIA to numerically estimate the production rates or background signals in high-energy collisions, while theorists use it to highlight possible signatures of beyond-standard-model physics. The shortcomings of PYTHIA were anticipated by theoretical work carried out by us and by our collaborators [10], which showed that PYTHIA disagreed significantly with theoretical predictions based on NRQCD. Now, the LHCb results have shown that PYTHIA also disagrees with experimental results.

The LHCb results will have two important implications for research on quarkonium and particle physics. First, it will spur improvements in Monte Carlo simulations, which are crucial for analyzing any particle-physics measurement. PYTHIA experts, who are working to refine the description of quarkonium production in the program, will certainly take note. Second, it will trigger theoretical and experimental work aimed at improving the extraction of NRQCD matrix elements. This may lead to important improvements of the NRQCD formalism, which is essential for understanding the complex physics of heavy quarkonium states.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

References

- J.-E. Augustin et al., “Discovery of a Narrow Resonance in e+e− Annihilation,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 33, 1406 (1974).

- J. J. Aubert et al., “Experimental Observation of a Heavy ParticleJ,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 33, 1404 (1974).

- T. Appelquist and H. D. Politzer, “Heavy Quarks and e+e Annihilation,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 43 (1975).

- R. Aaij et al. (LHCb Collaboration), “Study of J∕𝜓 Production in Jets,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 118, 192001 (2017).

- F. Abe et al. (CDF Collaboration), “J∕𝜓 and 𝜓 (2S) Production in pˉp Collisions at √s=1.8TeV,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 79, 572 (1997).

- G. T. Bodwin, E. Braaten, and G. P. Lepage, “Rigorous QCD Analysis of Inclusive Annihilation and Production of Heavy Quarkonium,” Phys. Rev. D 51, 1125 (1995); 55, 5853(E) (1997).

- P. L. Cho and M. B. Wise, “Spin Symmetry Predictions for Heavy Quarkonia Alignment,” Phys. Lett. B 346, 129 (1995).

- M. Baumgart, A. K. Leibovich, T. Mehen, and I. Z. Rothstein, “Probing Quarkonium Production Mechanisms with Jet Substructure,” J. High Energy Phys 2014, 003 (2014).

- T. Sjöstrand, S. Mrenna, and P. Z. Skands, “PYTHIA 6.4 Physics and Manual,” J. High Energy Phys. 2006, 026 (2006).

- R. Bain, L. Dai, A. Hornig, A. K. Leibovich, Y. Makris, and T. Mehen, “Analytic and Monte Carlo Studies of Jets with Heavy Mesons and Quarkonia,” J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 121 (2016).