Seeing Scrambled Spins

Physicists have long wondered whether and how isolated quantum systems thermalize—questions that are relevant to systems as diverse as ultracold atomic gases and black holes. Recent theoretical and experimental advances are bringing fresh insight into this line of inquiry. At one extreme, researchers have shown that disorder can fully arrest thermalization in certain isolated many-body quantum systems [1]. At the other extreme, surprising results from the field of quantum gravity have established that black holes are, in some sense, the fastest thermalizers in nature [2–4]. A common thread running through these developments is an emerging focus on the dynamics of quantum information, in which thermalization is associated with “scrambling,” or the loss of accessible information. Two groups, one in China [5] and one in the US [6], have taken a step towards tracking this scrambling of information in systems of quantum spins.

The lore of thermalization goes as follows. Suppose you initialize a collection of quantum spins into one of two distinct configurations. Now couple the system to a large heat bath. After equilibrium is reached, the final state of the spins will be independent of the spins’ initial configuration. In other words, information about the initial state of the spins has been irrevocably lost to the bath.

But thermalization does not require a bath to proceed. In a complex many-body quantum system, information about the initial state may instead be “hidden” in elaborate correlations among the system’s constituents. The information in such a scrambled state is not lost, because the final state can be related to the initial state by a unitary transformation. But it may be inaccessible to any reasonable local measurement.

The concept of information scrambling first arose in attempts to understand the black hole information paradox, which asks: How can information about what fell into a black hole be both trapped inside the event horizon and liberated as the black hole “evaporates” by emitting Hawking radiation? Since a black hole is fundamentally a thermal object, this paradox is intimately related to how information dynamics leads to thermalization. Specifically, one could imagine that when something falls into a black hole, the information about it is encoded—albeit in scrambled form—in the radiation emitted during evaporation.

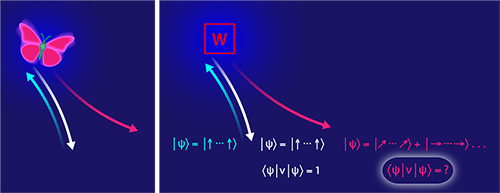

Experiments that can probe the quantum dynamics of black holes are currently out of reach. But scrambling is also relevant to isolated collections of strongly interacting atoms, ions, molecules, and photons—all systems that physicists can prepare in the lab. As a bonus, it may be possible to engineer Hamiltonians in these systems that scramble information as fast as black holes. The most direct way to detect scrambling would be to measure a system’s entropy over time, though this is typically too hard to do. Instead, researchers have figured out that they can partially diagnose scrambling using unusual correlation functions called out-of-time-order correlators (OTOCs) [2, 3, 7]. These correlators effectively involve a many-body “time machine.” Given two simple quantum operators W and V, one imagines comparing two processes: (i) Evolve the system forward in time, apply W, evolve backward in time, and apply V; (ii) apply V, evolve forward in time, apply W, and evolve backward in time.

What does this comparison tell you? Drawing on an analogy to classical chaos, one interpretation is that comparing the two processes reveals the sensitivity of a measurement of V to a perturbation W—say, a kick from an external field—that happened some time in the past. If the measurement is very sensitive to the perturbation, we have a quantum version of the classical butterfly effect, in which a small initial perturbation eventually has a major effect (Fig. 1). Taking the analogy further, a quantum system in which information becomes scrambled can be viewed as a quantum chaotic system, and the OTOC provides a measure of the scrambling.

Unfortunately, measuring OTOCs is difficult. Existing proposals [8–10] for doing so require the experimenter either to evolve a system forward in time under a Hamiltonian and then backwards in time by implementing the negative of this Hamiltonian or to make a delicate comparison of two many-body quantum states. Thanks to the growing toolbox of quantum-control techniques, these difficult tasks are now (somewhat) possible and the teams from China and the US have demonstrated proof-of-principle measurements of OTOCs.

Jun Li, from the Beijing Computational Science Research Center, and colleagues used four nuclear spins in the iodotrifluroethylene molecule [5]. After preparing the spins in a particular initial state, they applied a sequence of control pulses to engineer a quantum simulation of the mixed-field Ising Hamiltonian, evolving this Hamiltonian forward in time. After perturbing the spins, they used another series of control pulses to implement the negative of the Ising Hamiltonian, thus enabling the necessary “rewinding” of time, and again evolved the spins. Their measurement of the final spin state effectively yields the OTOC. But while their Hamiltonian is, in principle, chaotic, the system size is so small that its full evolution can be directly simulated on a computer, and it is far from the limit of many-body chaos.

Martin Gärttner, from the University of Colorado Boulder, JILA, and the National Institute of Standards and Technology (all in Boulder, Colorado) [6], and colleagues studied the dynamics of a much larger system consisting of more than one hundred 9Be+ ions confined in a two-dimensional electromagnetic trap. The valence electron spin of each ion behaves as an S=1∕2 magnetic moment. The Boulder team implemented a long-range classical Ising Hamiltonian by using a laser to couple the spins to the motional modes of the ion crystal. Then, using a protocol analogous to that of the team from China, they evolved the system “forward” and “backward” in time to measure the OTOC. The general dynamical evolution of one hundred two-level quantum systems is well beyond what physicists can simulate on a classical computer. However, the team confined its experiment to the dynamics of a more tractable subspace of quantum states. Moreover, despite the large number of spins in their experiment, the spin Hamiltonian that they engineered was not chaotic, and their measurements of OTOCs, like those of the molecular spin experiment, took place far from the limit of many-body scrambling.

While neither experiment reaches the limit of true many-body chaos, both raise crucial questions. Can one distinguish information that is scrambled from that which is simply lost because of environmental noise and spin decoherence? Can one correct for small errors that result from imperfectly evolving a system backward in time? Using the rich data set from their ion experiment, Gärttner et al. were able to explore and model various sources of such imperfection such as magnetic-field noise.

Quantum thermalization is a rapidly developing field. In fact, two new scrambling experiments appeared just recently [11, 12]. The near future promises experiments of increasing complexity—both larger system sizes and more chaotic Hamiltonians. Building on the work by Li et al. and Gärttner et al., it seems likely that experiments will soon forge beyond what computers can simulate, revealing the dynamics of information scrambling in previously inaccessible regimes.

This research is published in Physical Review X and in Nature Physics.

References

- R. Nandkishore and D. A. Huse, “Many-Body Localization and Thermalization in Quantum Statistical Mechanics,” Annu. Rev. Cond. Matt. Phys. 6, 15 (2015).

- S. H. Shenker and D. Stanford, “Black Holes and the Butterfly Effect,” J. High Energy Phys. 2014, 67 (2014).

- A. Kitaev, Talk at Fundamental Physics Prize Symposium Nov. 10, 2014.

- J. Maldacena, S. H. Shenker, and D. Stanford, “A Bound on Chaos,” J. High Energy Phys. 2016, 106 (2016).

- J. Li, R. Fan, H. Wang, B. Ye, B. Zeng, H. Zhai, X. Peng, and J. Du, “Measuring Out-of-Time-Order Correlators on a Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Quantum Simulator,” Phys. Rev. X 7, 031011 (2017).

- M. Gärttner, J. G. Bohnet, A. Safavi-Naini, M. L. Wall, J. J. Bollinger, and A. M. Rey, “Measuring Out-of-time-order Correlations and Multiple Quantum Spectra in a Trapped-ion Quantum Magnet,” Nat. Phys. (2017).

- A. I. Larkin and Yu. N. Ovchinnikov, Zh. Eksp. Teor. Fiz. 55, 2262 (1969), [Sov. Phys. JETP 28, 1200 (1965)].

- B. Swingle, B. Bentsen, M. Schleier-Smith, and P. Hayden, “Measuring the Scrambling of Quantum Information,” Phys. Rev. A 94, 040302 (2016).

- N. Y. Yao, F. Grusdt,, B. Swingle, M. D. Lukin, D. M. Stamper-Kurn, J. E. Moore, and E. A. Demler, “Interferometric Approach to Probing Fast Scrambling,” arXiv:1607.01801.

- G. Zhu, M. Hafezi, and T. Grover, “Measurement of Many-Body Chaos Using a Quantum Clock,” Phys. Rev. A 94, 062329 (2016).

- K. X. Wei, C. Ramanathan, and P. Cappellaro, “Exploring Localization in Nuclear Spin Chains,” arXiv:1612.05249.

- E. J. Meier, J. Ang’ong’a, F. A. An, and B. Gadway, “Exploring Quantum Signatures of Chaos on a Floquet Synthetic Lattice,” arXiv:1705.06714.