Landauer Principle Stands up to Quantum Test

Erasing information always produces heat, even when erasing just one bit of information. This expectation, which has implications for computer science and information technology, dates to 1961, when Rolf Landauer predicted that the minimum amount of heat needed to erase a classical bit is kBTln2 [1]. ( kB is the Boltzmann constant and T the temperature of a “reservoir” with which the bit exchanges heat.) Landauer’s classical limit was confirmed a few years ago using trapped micrometer-sized colloidal particles to encode the bits [2, 3]. But in the era of quantum computers, one may wonder if there is a way around the principle; after all, quantum and classical bits are fundamentally different. The answer, according to new experiments, is no. A team led by Mang Feng of the Chinese Academy of Sciences in Wuhan reports the first experimental verification of the Landauer principle in a fully quantum system, in which the bit and the heat reservoir have quantized energies [4].

Landauer’s novel approach described a classical bit using a concept from information theory known as Shannon entropy, which characterizes information content. Consider a bit that can be 1 or 0. If you know the bit is always 1, reading a 1 doesn’t yield any information because you expected this result already. Whereas if the bit is equally likely to be 1 or 0, you don’t know what to expect from a reading, so any reading is a surprise. In other words, information on a bit is greatest if measuring it yields the greatest surprise. As explained in the note in Ref. [5], the Shannon entropy is equal to kBln2 for a “maximally surprising” bit and equal to 0 for a “no-surprise” bit.

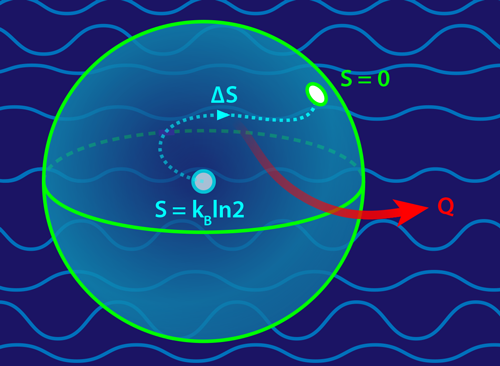

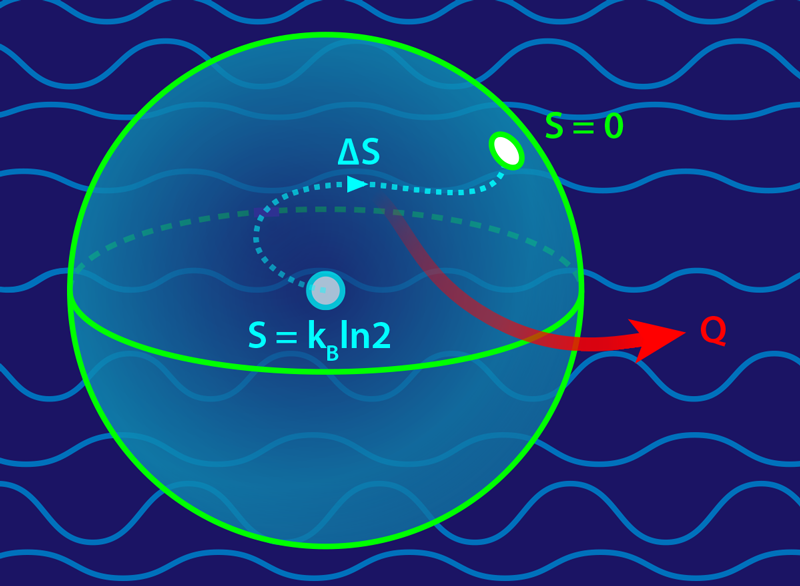

The connection between Shannon entropy and physics was initially unclear. But thanks to advances in stochastic thermodynamics [6, 7], the Landauer principle is now understood to be a direct consequence of the second law of thermodynamics, which states that entropy production Σ never decreases. For a system exchanging heat with a reservoir, Σ=ΔS+Q∕T, where ΔS is the system’s change in entropy during some process and Q is the resulting heat released. Erasing information on a classical bit corresponds to changing the Shannon entropy from its maximal value ( kBln2) to its smallest (0) value, or an entropy change of −kBln2. Plugging this into the second law ( Σ=ΔS+Q∕T≥0) predicts a release of heat Q≥kBTln2, just as Landauer predicted.

The challenge in confirming the Landauer principle experimentally for a classical system was that such systems are usually described by a continuum of states, rather than the two discrete states required for a classical bit. The first experimental confirmations made an effective two-state system by using laser light [2] or electric fields [3] to confine a Brownian particle in a controllable double-welled potential.

In contrast with a classical bit, a quantum bit (or qubit) is a genuine two-level system, and it can be in a superposition of states. Instead of a classical probability distribution, a qubit is described by a density matrix 𝜌; and the entropy becomes the von Neumann entropy [ S=−kBTr(𝜌ln𝜌), where Tr stands for trace]. With these changes, one can derive a quantum version of the second law [8] and, in turn, the quantum version of the Landauer principle [6, 9]. The quantum version of the principle makes the same prediction as its classical counterpart: the erasure releases at least −TΔS of heat. And for the case in which a maximal-entropy qubit is completely erased, this amount of heat is kBTln2. Entropy production can also be expressed as the reservoir’s deviation from equilibrium and correlations between the system and the reservoir. These quantities are, however, notoriously difficult to measure.

Taking on this challenge, Feng and colleagues [4] conducted an ingenuous experiment to verify the Landauer principle in the quantum regime. In their setup, the qubit was comprised of two internal states of a trapped calcium ion. The heat reservoir was supplied by the ion’s own vibrational modes, which were cooled to a few tens of microkelvin. At the start of the experiment, the researchers prepared the qubit such that its two states were equally populated, a condition of maximal entropy known as a classically mixed state. They then “erased” part of this information using a laser, which coupled the qubit to the reservoir and enabled the conversion of entropy into heat (Fig. 1). By taking multiple measurements of the ion, the team recovered the population of the atom’s two levels and the population of the vibrational modes. Comparing populations before and after an erasure, the team determined all terms appearing in the second law (Σ,Q,ΔS) and showed that the Landauer principle holds in the quantum regime. The team also found that achieving close to zero entropy production with a quantum reservoir was very difficult, particularly at low temperatures.

What’s next? As formulated, the quantum Landauer principle assumes that the qubit is initially uncorrelated with the equilibrated reservoir. This assumption is valid in the method Feng’s team used to prepare the qubit [4] or when the interaction between the qubit and the reservoir is weak. However, formulating second laws for correlated initial conditions is harder and remains an active field of research.

The ideas behind the Landauer principle and, more generally, information thermodynamics are fascinating on a fundamental level. But they also have practical value. They can, for example, be used in biology to assess the energetic cost of a cell processing information as it chemically senses its surroundings, copies DNA, or detects and repairs cellular structures [10]. The same ideas also allow us to determine the trade-off between energy, speed, and accuracy in any computation. This capability is a priority for the emerging field of green computing, which aims to moderate the energy consumption of our information technologies. Ultimately, the Landauer bound could end up being to computation what the Carnot bound is to heat engines: a fundamental limit that sets a target for practical applications.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

References

- R. Landauer, “Irreversibility and Heat Generation in the Computing Process,” IBM J Res. Dev. 5, 183 (1961).

- A. Bérut, A. Arakelyan, A. Petrosyan, S. Ciliberto, R. Dillenschneider, and Eric Lutz, “Experimental Verification of Landauer’s Principle Linking Information and Thermodynamics,” Nature 483, 187 (2012).

- Y. Jun, M. Gavrilov, and J. Bechhoefer, “High-Precision Test of Landauer’s Principle in a Feedback Trap,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 113, 190601 (2014).

- L. L. Yan, T. P. Xiong, K. Rehan, F. Zhou, D. F. Liang, L. Chen, J. Q. Zhang, W. L. Yang, Z. H. Ma, and M. Feng, “Single-Atom Demonstration of the Quantum Landauer Principle,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 120, 210601 (2018).

- Shannon entropy is defined as −(p1lnp1+p2lnp2+…) where p1 , p2, etc., are the probabilities the system is in state 1, 2, etc. A two-level system that is equally likely to be in either state (p1=p2) has maximal entropy, S=ln2 . If the system is definitely in one state (e.g., p1=1 and p2=0 ) the entropy is smallest and equal to 0. (Strictly speaking, the Shannon entropy has to be multiplied by Boltzmann’s constant to yield the entropy of thermodynamics.).

- M. Esposito and C. Van den Broeck, “Second Law and Landauer Principle Far from Equilibrium,” Europhys. Lett. 95, 40004 (2011).

- T. Sagawa, “Second Law, Entropy Production, and Reversibility in Thermodynamics of Information,” arXiv:1712.06858.

- M. Esposito, K. Lindenberg, and C. Van den Broeck, “Entropy Production as Correlation Between System and Reservoir,” New J. Phys. 12, 013013 (2010).

- D. Reeb and M. M. Wolf, “An Improved Landauer Principle with Finite-Size Corrections,” New J. Phys. 16, 103011 (2014).

- R. Rao and M. Esposito, “Nonequilibrium Thermodynamics of Chemical Reaction Networks: Wisdom from Stochastic Thermodynamics,” Phys. Rev. X 6, 041064 (2016).