How Walkers Avoid Collisions

Pedestrians can move seamlessly through crowds without running into each other as if following some innate “collision avoidance radar.” Scientists trying to understand this behavior typically must contend with the inherent irregularities in human activity. Two new studies now make detailed observations of pedestrians in a number of different settings, finding that a walker spontaneously changes their stepping movements when another walker gets too close. The results provide needed details on pedestrian-pedestrian interactions that could help architects and engineers design walkways for smoother and safer traffic flow.

Physicists model pedestrian walking patterns by assuming that they are driven by “social” interactions, like avoiding the “comfort zones” of other pedestrians. In order to accurately characterize such interactions, Alessandro Corbetta, from Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, and colleagues utilized a state-of-the-art tracking system to collect five million individual pedestrian trajectories at the Eindhoven train station over a six-month period. The team selected events with two people moving in opposite directions. They found that whenever the intended walking routes came within 1.4 m, the two pedestrians adapted their trajectories to steer clear of each other. Based on this observed behavior, the team developed a collision-avoidance model that incorporated both a long-range (sight-based) interaction and a short-range (hard-contact-avoidance) interaction.

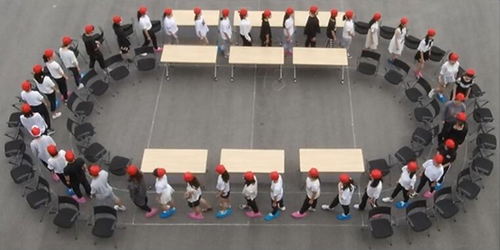

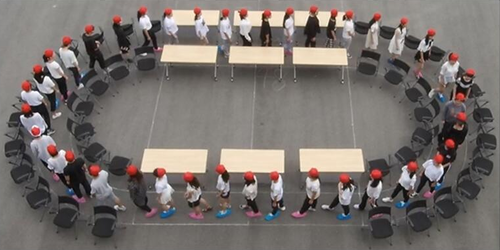

In a second experiment, Yi Ma, from Sichuan University, China, and co-workers observed volunteers moving around a 20-m-long track in a single file. As in previous studies, Ma and colleagues observed the head motion of the volunteers. They also filmed the walkers’ foot movements, from which they measured step length and duration. The team found an average step length of about 60 cm when the walker separation exceeded 1.2 m. However, the step length—and step duration—decreased under more crowded conditions.

This research is published in Physical Review E.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics based in Lyon, France.