Postcard: Physics in Argentina

Chat with any Argentinian physicist and, inevitably, the conversation turns to the economic crisis. Since 2015, the peso has plummeted around sevenfold against the US dollar, and grants that were once enough to start up a lab are now barely enough to sustain it. With dwindling travel funds, one senior scientist said she had to lean on collaborators in the US in order to fly there for an invited talk.

Argentinian physicists are adamant that the country’s success depends on a stable investment in science. But they also state it as a point of pride that they’ve made it through downturns like this one before, taking a creative approach that lets them stay competitive even if they can’t buy the fanciest equipment.

“Sometimes crisis gives you the opportunity to think outside the box,” says Hernan Grecco, who heads the physics department at the University of Buenos Aires school of science. He says the country would benefit from a larger investment in science, but “the science output normalized to the money put in—it’s actually very good.”

I visited Argentina in early October, just as trees were abloom with pink flowers and a dreary rain gave way to sun in bustling Buenos Aires. My first stop was in Santa Fe where I gave a talk at a workshop for women in physics that coincided with this year’s meeting of the Argentine Physical Society (AFA). I also visited the University of Buenos Aires, where 40% of Argentina’s physicists train, and the Bariloche Atomic Centre (CAB), a large scientific research campus in Patagonia that’s home to the prestigious Balseiro Institute for physics and engineering.

And while the economy loomed in conversations with researchers, it was clearly only one of many influences shaping physics.

One push comes from a recent wave of feminism sweeping through the country. In 2015, thousands of Argentines took to the streets protesting gender violence, furious that rape and murder of women had become so commonplace. The movement, known as Ni una menos (not one woman less), spawned further protests, while also motivating activism on women’s health, social standing, and professional rights. Even the rules of the patriarchal tango are getting a reboot.

Ni una menos heightened awareness of feminist issues says Cecilia Cormick, a quantum information theorist at the National University of Cordoba, and my host for the workshop. The movement started with “don’t kill us.” Now, she says, women “want more than just to live.”

In 2017, Cormick was one of several physicists who complained to AFA when it announced an all-male list of eight plenary speakers for the annual meeting. Ultimately, the society made a rule that plenary sessions should mirror the gender balance of its membership (30% women). AFA also formed its first gender subcommittee. The Santa Fe workshop for women was the subcommittee’s initiative, and it struck a balance between political discussion and practical-skills training, like publishing and applying for grants.

Some physics departments in Argentina boast an already strong female representation, such as the one at UBA, where women comprise 30–35% of students and faculty. But women make up only 10% of the undergraduates who take the continent-wide entrance exam for Balseiro, says Karen Hallberg, a condensed-matter theorist at CAB and this year’s winner of the Latin American L’Oréal prize for Women in Science.

The institute’s elite reputation and its remote location might both be deterrents, she says. Many young women, she believes, would rather not live so far from home. Attracting more women to physics, Hallberg feels, requires continued outreach and practical support, like affordable child care. “I think it’s a question of putting the burden not only on women but on all of society,” she says.

Another influence on physics comes from academic departments and societies, which are trying to build connections between students and industry. Grecco of UBA says very few physicists who train in Argentina leave academia to take industry jobs. One issue, he says, may be that the country’s yo-yoing economy scares off start-up companies. He contrasts this situation with places like the US and Germany, where start-up culture is strong and attracts the best Ph.D.s by offering high salaries.

Students may also be biased against the money-making image of industry, which can seem like a “sacrilege” to the purity of research, says Alex Fainstein, who heads the CAB physics department.

Grecco plans to encourage industrial ties by hosting a meet-and-greet with company heads next year. Argentina’s strongest industries, he says, include petroleum, satellites, optical communications, and packaging materials. One of Argentina’s most successful tech companies is INVAP, which is based in Bariloche and has sold nuclear reactors to Algeria, Egypt, and Australia.

Argentina is a popular destination for astrophysics, with its vast flat regions that offer a clear view of the Southern Sky. Several large-scale experiments attract researchers from around the world, including the Pierre Auger observatory, a massive cosmic-ray detector near the city of Malargüe that involves 16 collaborating countries. The project is undergoing a major upgrade, dubbed Auger Prime, which will help researchers unveil the mysterious sources of the highest-energy cosmic rays hitting Earth.

Planning is also underway for the Agua Negra Deep Experiment Site (ANDES), which would be Latin America’s first major underground lab for astrophysics and geophysics. The lab is contingent on the completion of several trade tunnels that will cross the Chilean-Argentine border. Further along is the QU Bolometric Interferometer for Cosmology (QUBIC), a detector designed to look for signs of cosmic inflation in the cosmic microwave background.

The warmth and ebullience of Argentines can make you forget that they are dealing with a rough economy. Most researchers acknowledged that a lack of funds slowed them down and made travel to conferences difficult. And the prospect of more journals turning to an open-access model left some wondering how they would pay to publish papers. But many have also cultivated a talent for navigating uncertain funding.

Gabriel Mindlin, whose group at UBA unravels the physics of birdsong, says he keeps his lab afloat by picking projects that allow him to seamlessly shift from experiments to computations when money is tight. “You have to find [topics] that have impact but that can be sustained during times of crisis,” he says.

Enzo Tagliazucchi, also at UBA, studies the physics of consciousness—a problem so vast and ill-defined that even the world’s top universities can’t lay claim to having answers. “Argentina is the place to tackle more ambiguous topics,” he says.

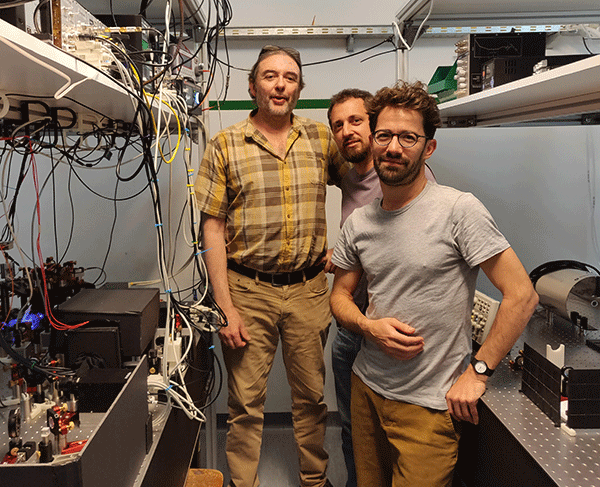

Christian Schmiegelow offered a grimmer take. An experimentalist who works with trapped ions, he returned to Argentina in 2015 to set up a lab at UBA. The lure was a sizable start-up grant, the encouragement of UBA's physics department, and the opportunity to work with Juan Pablo Paz—a preeminent quantum information theorist. As the peso fell, Schmiegelow and Paz had to hold off on several planned experiments. Both are concerned that the crisis will dissuade talented young scientists from planting roots in Argentina.

My visit ended a few weeks before the presidential election. The winner was Alberto Fernández, who is considered more science friendly than the outgoing president, Mauricio Macri. Over 10,000 researchers supported Fernández in a public letter, citing hopes that he will bring more support to science and technology.

The political future came up in a conversation with Gustavo Alberto Monti, the president of AFA, who met with me in Santa Fe. Monti speaks softly and isn’t prone to bold statements. But reflecting on Argentina’s scientific future, he said this: “Our country will not be successful if we don’t keep science and technology strong. It’s not enough to be a country of sports and food. We need a strong scientific system.”

–Jessica Thomas

Jessica Thomas is the Editor of Physics.