Collection of Disks Mimics Earthquakes

The frequency and sizes of earthquakes at a particular location follow universal statistical laws that have been difficult to accurately replicate with lab-scale analogs. A new experiment that continuously shears a collection of small disks confined to a 2D cylindrical shell has compiled over a million “labquakes,” an exceptionally large data set that exhibits three important seismicity laws. The key to this success, say the researchers, is the disorder inherent in the constantly evolving networks of force that transmit stress throughout the array of disks. Further work with this system could help researchers isolate the factors that control real earthquakes.

The likelihood of an earthquake depends on where you live. In parts of Japan, for example, large earthquakes (greater than magnitude 8) occur once every 10 years on average, whereas California sees a large earthquake roughly every 150 years. However, if you plot the logarithm of the number of events vs earthquake magnitude, you find that the lines for Japan and California have nearly the same slope, given by the Gutenberg-Richter law. A related law characterizes the time between two quakes of similar magnitude. A third important law from seismic studies is the Omori law, which describes the number of foreshocks and aftershocks that accompany a large earthquake.

To understand such laws, researchers try to reproduce them in the controlled setting of a lab (see 19 February 2013 Viewpoint). For example, a rock can be compressed until quake-like cracks form, or a large collection of small particles or grains can be subjected to an overall shear stress until they slip past each other, which is another quake-like phenomenon. Although previous experiments have recreated certain aspects of seismic behavior, they have not been able to quantitatively match several statistical laws simultaneously.

For their experiment, Osvanny Ramos from the University of Lyon in France and his colleagues used a 2D system of 3500 disks that were 7 mm or less in diameter. Unlike previously studied particles that were confined in a flat geometry, these disks were contained in the narrow space between two concentric, vertical cylinders, which allowed the experiment to be run continuously. The top edge was covered with a weighted ring to induce pressure on the disks, while the bottom edge was rotated at a rate of one revolution every 18 hours. The corresponding linear velocity was roughly 50 mm per hour, which is 12,000 times faster than the movement of the San Andreas fault in California.

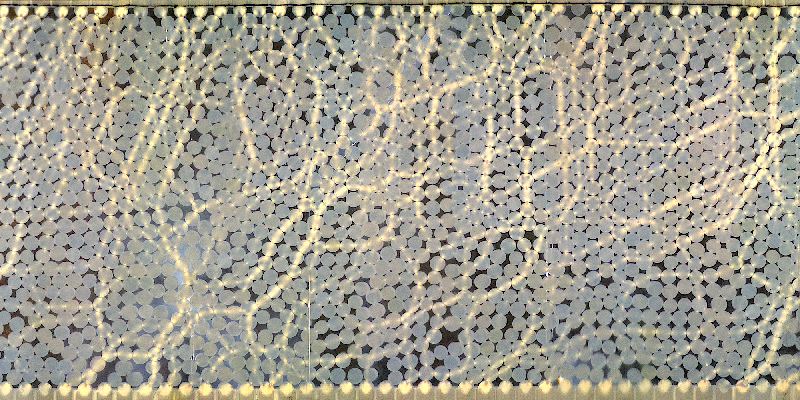

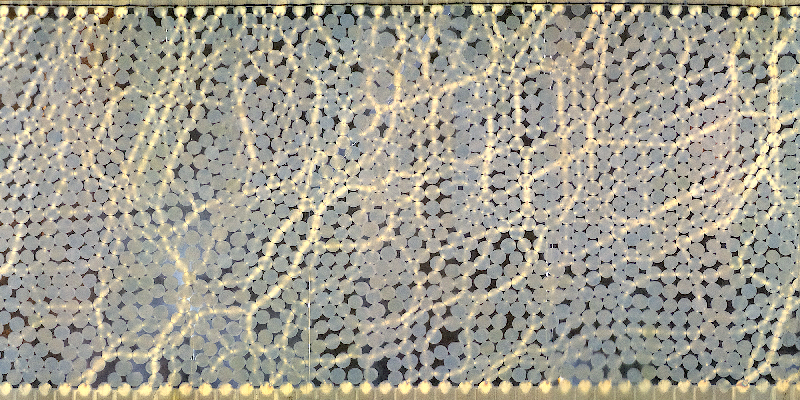

Ramos and colleagues monitored their system with 24 cameras, a torque sensor, and an array of acoustic detectors. The cameras captured the network of forces transmitted throughout the system (force chains) by exploiting the stress-dependent light transmission property of the disks. The continuous shifting of force chains (see video) indicated that the system was randomly sampling a wide variety of disk configurations. Previous lab-based earthquake experiments may not have had enough of such disorder, Ramos says.

The torque data showed a series of sudden drops in the amount of force on the top ring, resembling the energy-releasing slips that occur between tectonic plates at geological fault lines. At the same time, the compacted disks continuously shifted relative to each other, causing acoustic emissions that can be thought of as seismic waves. During a 24-hour period, the number of torque drops was around 2000, while the number of acoustic emissions was nearly 2 million. The team estimated the energy (“magnitude”) of these events and showed that the distribution exhibited behavior consistent with the Gutenberg-Richter law, the inter-event law, and the Omori law.

Having a reliable analog system that matches geological observations “may lead to finding the essential ingredients that govern the dynamics of real earthquakes,” Ramos says. In future work, he and his colleagues will try modifying key parameters, such as the pressure and rotation speed, to see how these affect the labquake behavior. They also plan to look for possible precursors that might signal the arrival of a large event.

This is “a beautiful paper,” says engineer Itai Einav from the University of Sydney. “What I find particularly exceptional is that these data exhibit the salient features of real earthquakes.” Eduard Vives, from the University of Barcelona in Spain, who has also performed earthquake analog experiments, says that the continuous manner of data collection allowed Ramos and his colleagues to observe rare events and aftershock behavior that were not seen in previous efforts.

This research is published in Physical Review Letters.

–Michael Schirber

Michael Schirber is a Corresponding Editor for Physics Magazine based in Lyon, France.