Galactic Accelerometers Probe Milky Way’s Dark Side

Stars whiz through the Milky Way at hundreds of kilometers per second, but their velocities can slowly change under the gravitational pull of both visible bodies and dark matter structures. Such speed changes, however, are typically tiny: Over a year, they may amount to a few centimeters per second—about the pace of a crawling infant. A new study shows that binary pulsars in our Galaxy can be used as accelerometers that are sufficiently sensitive to characterize such “baby” velocity drifts. And, by relating these accelerations to the gravitational forces that cause them, researchers might be able to build a detailed picture of the distribution of dark matter in our home Galaxy and beyond.

The Universe is a violent arena, teeming with explosions, mergers, and cannibalistic galactic encounters. Most of what we know about these dynamics, however, comes from “snapshots” that capture the positions and velocities of astrophysical objects at a particular moment. From those data, astrophysicists can indirectly derive the objects’ accelerations. There’s a catch though. This derivation assumes that the system is in equilibrium. Take an isolated planetary system, for instance, where kinetic and potential energies are balanced, and all one needs to derive the planets’ accelerations are their positions and velocities.

In general, however, this equilibrium assumption isn’t justified. “There are many signs that the Milky Way isn’t in equilibrium,” says Sukanya Chakrabarti of the Institute for Advanced Study, New Jersey, and Rochester Institute of Technology, New York, who presented the results at the 237th AAS meeting. A recent study she led suggests, for instance, that certain ripples in the Milky Way are “scars” from a past crash with a faint dwarf galaxy called Antlia 2.

Chakrabarti and her collaborators thus set out to develop new, direct ways to measure accelerations. Their idea exploits pulsars, which are rapidly spinning neutron stars that emit radio-frequency beams from their poles. These beams, much like those of lighthouses, appear to us as intermittent flashes, timed at the pulsar’s spinning frequency. The extraordinary stability of this timing rivals that of atomic clocks, says Chakrabarti.

The technique characterizes subtle shifts of this precise timing, occurring when the pulsar orbits around a companion—typically a white dwarf—in a binary system. The tidal influence of the companion modulates the pulsar signal at the orbital frequency. And, if the binary moves, a Doppler-like effect changes the apparent orbital period. Monitoring this shift over time yields a direct measurement of the system’s velocity change, or acceleration.

Chakrabarti says that minuscule velocity changes can be directly extracted fr0m these measurements, using a simple model that doesn’t depend on hard-to-measure quantities like the pulsar’s magnetic fields. Thus, these pulsar binaries can serve as a network of accelerometers naturally embedded in our Galaxy as well as in other galaxies. For centuries, astronomers only had still images to work with, but this and other techniques allow galactic “movies” to be made, says Chakrabarti. “We are entering the era of real-time cosmology,” she says.

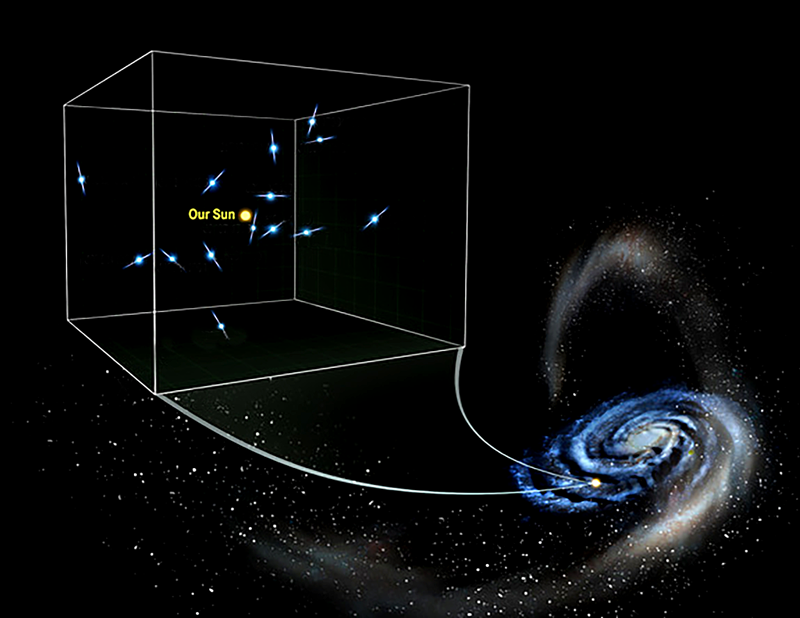

In the first application of the method, the team picked a set of 14 binary pulsars, chosen because their orbital period is stable and has been previously characterized with exquisite precision. The pulsars are located within a volume of 1 cubic kiloparsec (1 kiloparsec = 3262 light years) straddling both below and above the galactic plane where our Sun sits.

The method allowed the team to determine how the velocity of the 14 pulsars changed over a timescale of about ten years. From these measurements, the researchers inferred details of the gravitational forces acting in the Galaxy, deriving parameters that had previously been inferred from indirect acceleration measurements. They calculated, for instance, the average midplane density of matter and, by subtracting the contribution of visible matter, the average density of dark matter. The results hint at a possible discrepancy with previous estimates—a lower than expected dark matter density. “The discrepancy is tantalizing, but the error bars are still too large to claim there’s a serious conflict with most modern models,” says Chakrabarti.

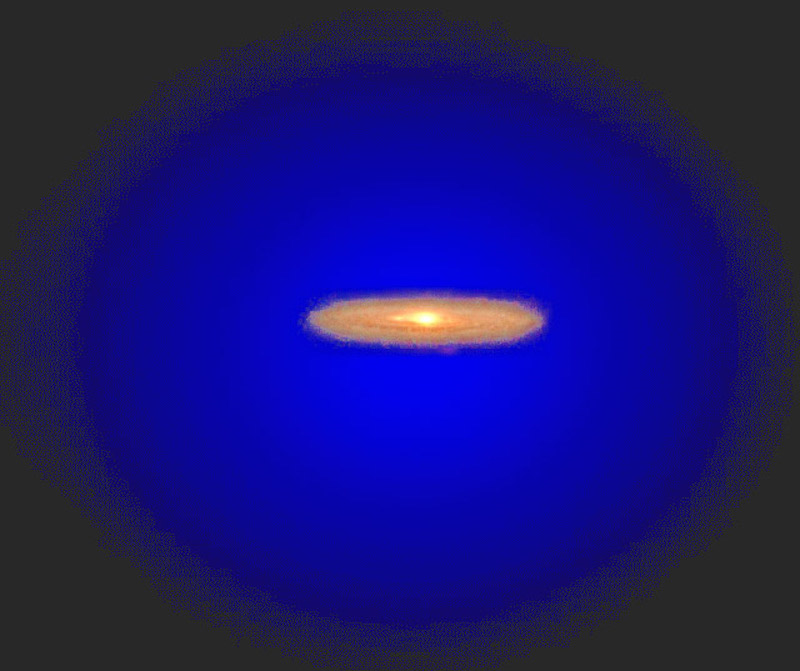

This, however, is only the first step of these kinds of studies, she says. The gravitational field of the 1-kiloparsec-wide volume in the current study is dominated by visible matter in the galactic disk. By probing pulsars lying 2–3 kiloparsec above or below the galactic plane, the researchers could start probing a region where the gravitational potential is much more strongly influenced by the dark matter in the spherical “halo” surrounding the Galaxy. “That’s when things would get really interesting,” says Chakrabarti.

The method has “tremendous potential,” and could become the standard for measuring our Galaxy’s gravitational potential, says David Hogg, a physicist at New York University. “There are very few places in the Universe where we can see accelerations, but accelerations really are the window into where the mass is and where the forces are,” he says. The characterization of the galactic gravitational potential, derived from just 14 binary pulsars, aren’t better than previous estimates based on the observations of thousands of stars. But Hogg says that by measuring many more pulsars and by increasing the measurement time, the improvement over previous analyses could be dramatic.

And that information could allow researchers to verify a fundamental prediction of cosmology that’s been extremely hard to test: According to the cold dark matter paradigm, the distribution of dark matter should be lumpy and chaotic—even more so than that of visible matter. “Starting to see that substructure would be incredibly exciting,” Hogg says.

–Matteo Rini

Matteo Rini is the Editor of Physics Magazine.