Neutrons Knock at the Cosmic Door

Spectroscopy has always set the pace of physics. Indeed, the observation of the Balmer series of the hydrogen atom led to the Bohr-Sommerfeld model about 100 years ago. A little later the discreteness of the spectrum moved Werner Heisenberg to develop matrix mechanics and Erwin Schrödinger to formulate wave mechanics. In 1947, the observation of a level shift in hydrogen by Willis E. Lamb ushered in quantum electrodynamics.

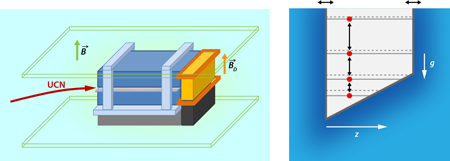

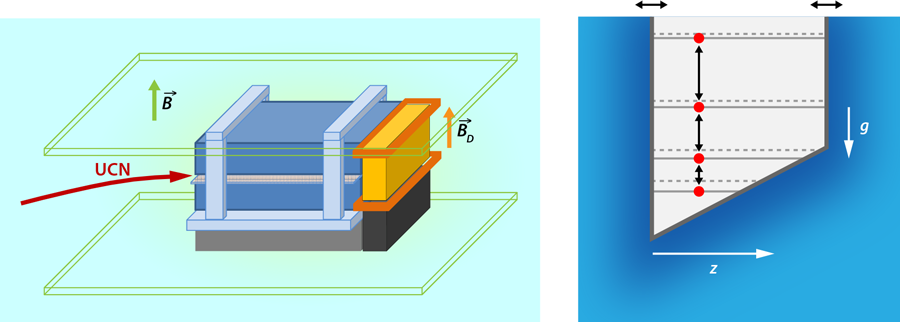

Now, a group led by Hartmut Abele of the Technical University of Vienna, Austria, reports, in Physical Review Letters [1], experiments that once more take advantage of the unique features of spectroscopy to put constraints on dark energy and dark matter scenarios. However, this time it is not a “real atom” (consisting of an electron bound to a proton) that provides the insight. Instead, the research team observes an “artificial atom”—a neutron bouncing up and down in the attractive gravitational field of the Earth (Fig. 1). This motion is quantized, and the measurement of the separation of the corresponding energy levels allows these authors to make conclusions about Newton’s inverse square law of gravity at short distances.

The energy wave function of a quantum particle in a linear potential [2], corresponding, for example, to the gravitational field close to the surface of the Earth, has a continuous energy spectrum [3]. However, when a quantum particle such as a neutron is also restricted in its motion by two potential walls, the resulting spectrum is discrete. This elementary problem of nonrelativistic quantum mechanics is a slight generalization of the familiar “particle in a box” where the bottom of the box, which usually corresponds to a constant potential, is replaced by a linear one representing the gravitational field.

In order to realize this “artificial atom,” Jenke et al. place neutrons between mirrors that act as two potential walls and then vary their separation in an oscillatory fashion. This modulation makes the neutrons climb up and down the energy levels in the gravitational box similarly to light-induced electronic transitions in an atom. This approach is reminiscent of the Fermi accelerator [4], which can be realized when an atom [5] bounces in the gravitational field of the Earth and is reflected from a time-dependent evanescent laser field at the lower end of the path of the atom. Transitions between the energy levels of the bound neutron manifest themselves in dips in the transmission curve as a function of the modulation frequency.

In their experiment, performed at the ultracold neutron facility at the Institut Laue-Langevin, Jenke et al. could measure the transition frequencies between the first four energy states. They use them to search for new kinds of hypothetical gravitylike interactions at micrometer distances and link their work to dark matter and dark energy.

While dark energy explains the accelerated expansion of the Universe, dark matter is needed to describe the rotation curves of galaxies and the large-scale structure of the Universe. However, the true nature of these forms of matter and energy are still not understood [6].

The central idea of the experiment by Jenke et al. rests on the fact that the interaction of so-far-undiscovered dark matter or dark energy particles with the neutrons caught between the two walls causes shifts in the energy levels. This approach is completely analogous to the measurement of the Lamb shift of the hydrogen atom, which is a verification of the quantization of the electromagnetic field (thus confirming the existence of the photon), or the Zeeman shift resulting from the spin of the electron.

Indeed, one candidate for dark energy is covered by “quintessence” theories [6], where in one scenario [7], a new hypothetical scalar field couples to matter. The associated interaction potential changes the energy of the bound neutron and a comparison of the observed transition frequencies to their theoretical ones yields constraints on the coupling strength of this field.

Likewise, a particle such as an axion, which is predicted to mediate a spin-dependent force that gives rise to an additional potential, couples the spin of the neutron to the position of a nucleon. In their search for dark matter based on such forces, Jenke et al. first polarize the neutrons at the entrance of the cavity by having them go through a foil coated by iron, and then they measure the transition frequencies again. The comparison to the theoretical values puts constraints on the coupling constant of this interaction.

The present experiment is in the tradition of the “COW” experiment [8] named after Robert Colella, Albert Overhauser, and Samuel Werner who first probed the gravitational field of the Earth with the matter waves of a neutron. More recently, matter-wave interferometers with cold atoms [9] have also served as probes of gravity and represent a very active field of research.

In particular, tests of the equivalence of the gravitational mass (the property of the particle that responds to the gravitational force created by other particles’ mass) and the inertial mass (the property that describes matter’s resistance to changes in motion) are being pursued in many laboratories. Although no experiment has so far revealed any difference between the two, they are conceptually different. It was recently pointed out [10] that they enter the energy wave function of a linear gravitational potential not as the ratio as expected from the weak equivalence principle but in different powers. Experiments like those of Jenke et al., which have already provided us with deeper insight of the cosmos using microscopic probes such as the neutron, will soon be able to verify this subtlety at the interface of gravity and quantum theory.

References

- T. Jenke et al., “Gravity Resonance Spectroscopy Constrains Dark Energy and Dark Matter Scenarios,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 112, 151105 (2014)

- G. Breit, “The Propagation of Schrödinger Waves in a Uniform Field of Force,” Phys. Rev. 32, 273 (1928)

- See, for example, W. P. Schleich, Quantum Optics in Phase Space (Wiley-VCH, Weinheim, 2001)[Amazon][WorldCat]

- E. Fermi, “On the Origin of the Cosmic Radiation,” Phys. Rev. 75, 1169 (1949)

- F. Saif, I. Bialynicki-Birula, M. Fortunato, and W. P. Schleich, “Fermi Accelerator in Atom Optics,” Phys. Rev. A 58, 4779 (1998)

- C. Wetterich, “Cosmology and the Fate of Dilatation Symmetry,” Nuclear Phys. B 302, 668 (1988)

- See, for example, D. F. Mola and D. J. Shaw, “Evading Equivalence Principle Violates Cosmological and other Experimental Constraints in Scalar Field Theories with a Strong Coupling to Matter,” Phys. Rev. D 75, 063501 (2007)

- R. Colella, A. W. Overhauser, and S. A. Werner, “Observation of Gravitationally Induced Quantum Interference,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 34, 1472 (1975)

- H. Müntinga et al., “Interferometry with Bose-Einstein Condensates in Microgravity,” Phys. Rev. Lett. 110, 093602 (2013)

- E. Kajari, N. L. Harshman, E. M. Rasel, S. Stenholm, G. Süßmann, and W. P. Schleich, “Inertial and Gravitational Mass in Quantum Mechanics,” Appl. Phys. B 100, 43 (2010)