Why Heat Moves Molecules in Solution

Charged molecules in water move from warmer to colder regions, an effect called thermophoresis that is part of a technique that allows researchers to monitor the binding of candidate drugs to proteins. Despite the technique’s popularity, no one has come up with a complete theory of thermophoresis. Now, Dieter Braun of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich, Germany, and colleagues have developed a theory that includes previously neglected contributions to the effect, as they report in Physical Review Letters.

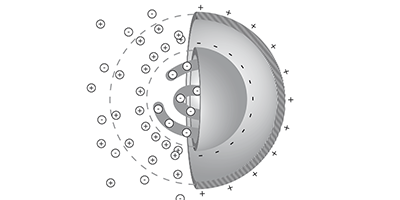

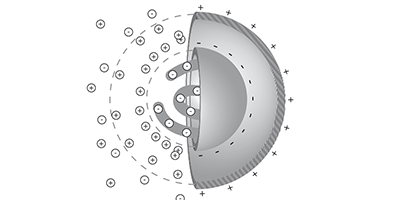

The new theory builds on the so-called capacitor model, previously developed by Braun and other colleagues, in which a charged macromolecule such as a wadded-up DNA strand acts like a spherical capacitor that drifts toward cooler regions to reduce its electric field energy. But the capacitor model alone could not account for some experiments. Braun and his colleagues have now added three additional contributions to their thermophoresis theory and tested it under a wider range of conditions. The first new contribution results from a difference in the temperature-induced motions of positive and negative ions in the solution, which leads to a charge imbalance that generates a weak electric field. The second contribution represents the weak dependence of the diffusion constant on temperature, and the third contribution comprises various non-ionic effects, which the researchers model with a simple empirical formula.

The team measured thermophoresis of fluorescently labeled DNA and RNA strands of various lengths and with a range of ions in the solution. Their model correctly predicted the temperature and concentration dependence of the effect, including nontrivial phenomena, such as a peak in the electrophoresis temperature dependence. – David Ehrenstein